The tension between Oman’s outward-looking coastal regions and its religious interior came to a head in the 20th century. Would the country be governed by sultan or imam?

In July 1970, the Sultan of Muscat and Oman was chased through his palace in Salalah by a contingent from his country’s Desert Regiment. Barricading himself in a room, Said bin Taimur was warned that, should he not surrender, he would be burned to death with a phosphorous grenade. With four bullet wounds and no feasible defence against the British-organised coup, the sultan acquiesced. He signed his abdication document and was taken to the Dorchester Hotel in London, where he died two years later of natural causes.

On the day that he was deposed in this violent coup, the sultan’s son, Qaboos, having agreed to the forced deposition of his father, spoke to the country he now ruled:

Yesterday it was complete darkness and with the help of God, tomorrow will be a new dawn on Muscat, Oman and its people.

July 2020 marks the 50th anniversary of this address. With the death of Qaboos in January, the story of his ascension to the throne reveals not only the longevity of Britain’s imperial interventionism during a supposed era of imperial decline, but also the resolution of a conflict at the heart of Oman’s fractious history.

Two conflicting historical and political traditions came into conflict in Oman during the 20th century and were resolved by the accession of Qaboos. The country’s interior was a stronghold for the Ibadhi Islamic tradition, which opposes sultanic rule. Yet Oman’s coastal areas – in particular its capital, Muscat – embraced sultanic rule, maritime trade and international exchange.

The history of Ibadhism as an Islamic sect begins with the crisis and civil war that followed the death of Muhammad. While Sunni and Shia split over Muawiyah’s claim to be the Fourth Caliph instead of Ali, a breakaway movement of Ali’s followers formed a secessionist group. The Kharijites opposed Ali’s decision to submit his conflict with Muawiyah to arbitration after the Battle of Siffin in AD 657. To the Kharijites, political arbitration by mortals could not subvert what they perceived to be the will of God: Ali’s legitimate leadership. One section within this group disagreed with the violent and exclusionary principles of the wider Kharijite movement that led to Ali’s assassination. This moderate strain called itself Ibadhi, deriving its name from the Basra-based scholar Abd Allah ibn Ibad.

A mosque in Nizwa, Oman.

A mosque in Nizwa, Oman.

Ibadhism formally established itself around 750 in the south-east of the Arabian peninsula, in what is now Oman. Before this, decades of political dispute with Ummayad authorities had pushed Ibadhi scholars out of Iraq and into Oman, where they created the first Imamate of Oman with its centre in Nizwa. This polity held unique core principles. One was the free election of an imam who would be an amalgamation of a religious and political leader, ruling through a process of shura, or consultation. Ibadhi political thought completely opposed the idea of hereditary succession and despotic rule by a king or sultan.

The imamate had its spiritual foundations and sovereignty in the land of Oman. It fought both the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates and later, colonial powers, in defence of this sovereignty. The election of the first Imam of Oman, al-Julanda bin Mas’ud, took place in the eighth century and the process was repeated intermittently until the 20th century. However, in Oman’s coastal regions, another polity would emerge based on hereditary rule with a different history.

The coastal cities and ports of Oman have long been the sites of international expansion, exchange and diplomacy. Muscat was the site for the expansion of the maritime Omani Empire, which at its 19th-century peak would stretch from the Arabian Gulf to East Africa and include parts of modern Iran. Omani settlers arrived in East Africa and began slave trading in the 16th century. When, in the 17th century, Portuguese colonial powers were expelled from Muscat, they were also expelled from areas in East Africa which Muscat took under its dominion. After the Omani Empire’s dissolution in the 19th century, the British organised the division of the East African dominions from the Gulf in 1861.

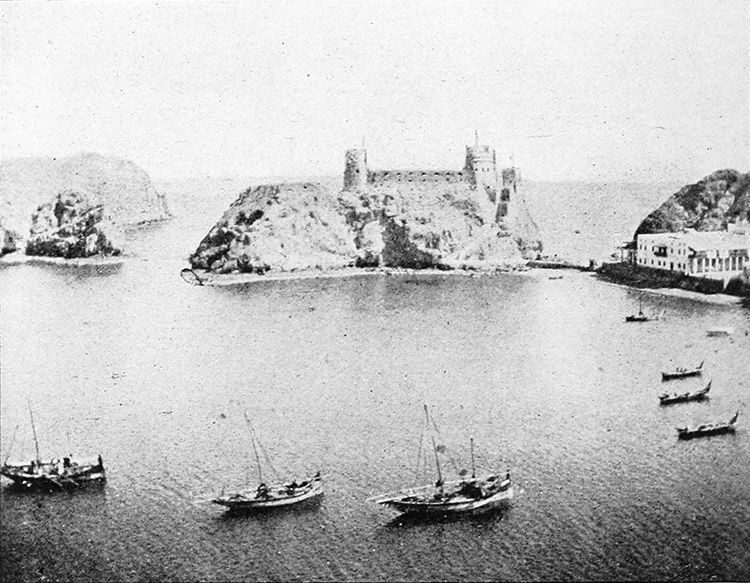

Muscat harbour, 1903.

Muscat harbour, 1903.

The coast that was the foundation of Oman’s imperial activities, was also of interest to European imperialism. During the peak of Oman’s maritime power, from the 17th century to the beginning of the 19th century, both Britain and France vied for influence over the region. Ultimately, Britain won out. Oman’s location between Britain and India meant that throughout the 18th and 19th centuries Britain adopted a colonial relationship with the rulers of Muscat. In 1800, Captain John Malcolm dubbed ‘the famed commerce of Muscat’ as indispensable to British interests in the Indian Ocean.

The importance of Muscat laid the foundations for the Al Bu Said Dynasty to establish a sultanate in 1792. The benefit of having a single absolute ruler, residing in Muscat, with whom international powers could deal, dictated the future of Oman. Throughout the 19th century, Britain increasingly supported the sultans, an arrangement that reached its apotheosis with the formal guarantee of British protection in 1886. Meanwhile, the ambiguous relationship between sultanic rule in Muscat and the elected imamate in the interior was becoming strained. But it was not until the 20th century that this problematic division became manifest.

With the accession of Said bin Taimur in 1932 came a concerted effort to unify Oman under the power of the new sultan. Driving this was British interest in oil exploration in the interior, then controlled by the imamate. In 1937, Said bin Taimur signed a lucrative oil concession with Petroleum Concessions Ltd, a subsidiary of the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) consortium. In order to explore the interior, however, the IPC needed an expeditionary force which they formed and funded with British government approval. Through such foreign-funded expeditionary forces, the sultan was beginning to realise his ambition of bringing the interior under his rule.

In response to these encroachments, the imamate decided to assert its national sovereignty. When Imam Muhammad al-Khalili died in 1954, his successor, Ghalib al-Hinai, began asserting the imamate’s sovereignty. The question of sovereignty had been left ambiguous since the 1920 Treaty of Seeb which created a fragile modus vivendi between the sultan and the imam. This modus vivendi died with Imam al-Khalili. The imamate began issuing passports and applied for membership to the Arab League during a period of renewed interest in Pan-Arabism and national self-determination around the region. This lead to an outright rebellion against the sultan’s claim over them which, by 1959, had been defeated with British help. Britain upheld its historic promise to support the sultan.

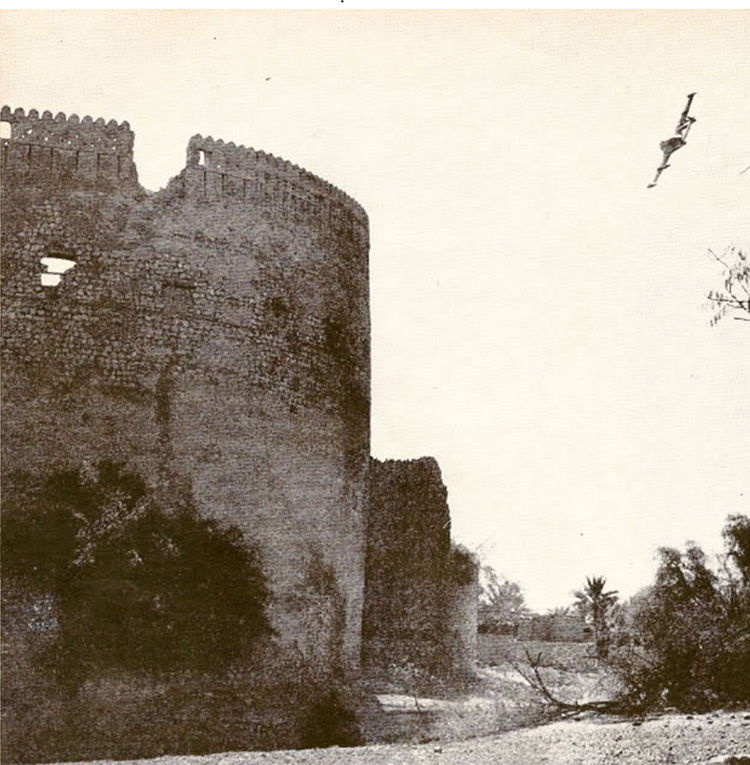

British plane attacking Nizwa Fort during the Jebel Akhdar War, 1958.

British plane attacking Nizwa Fort during the Jebel Akhdar War, 1958.

The exiled imamate leaders petitioned the United Nations against British aggression. During the 1960s the ‘Question of Oman’ was raised annually with the General Assembly. After debates and an extensive report it was concluded that the ‘problem derives from imperialistic policies and foreign intervention’. Interviewing people from across Oman, it also found that while there was support for an elected head of state, ‘there was little support for the sultan’. But ultimately the merits of the case never mattered; British interests and force were overwhelming.

In June 1965 a revolutionary socialist movement called the Dhofar Liberation Front declared: ‘a revolutionary vanguard has emerged from among you’ and ‘has taken upon itself the task of liberating this country from the rule of the despotic Al Bu Said Sultan whose dynasty has been identified with the hordes of the British imperialist occupation’. Originating in the Dhofar region of Oman near the border with Yemen, this group sought to militarily oppose the sultan as well as to fix the poverty, illiteracy and the lack of social services that the Omani people had suffered from. While the revolutionary movement went through different iterations under various names, its core principles and opposition to the sultan remained constant.

To fight this revolutionary force Said again relied on the British, particularly the Royal Air Force, to quell the rebellion. However, the British government realised that military suppression could not by itself legitimise the sultan. Some form of development and state formation would need to follow. A new ruler was necessary. They decided that Said’s pro-British son Qaboos should take over. By 1970 the British government, fearing the popularity of the revolutionary forces and the ineptitude of the sultan, devised a coup to save the sultanate as a political institution, a power Britain had spent centuries fostering.

It was then only a matter of execution. Between June and July in 1970 a series of reports, notes and memos were circulated between the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Ministry of Defence in support of the idea that the sultan’s son Qaboos should be put in power. It was noted by the Arabian Department that ‘once he were firmly in the saddle, he would carry out reforms sufficiently quickly to achieve a significant reduction in discontent’. Sultan Qaboos did exactly that and pursued a programme of reforms that co-opted many of the plans of the revolutionary groups, providing education, healthcare and improved social services.

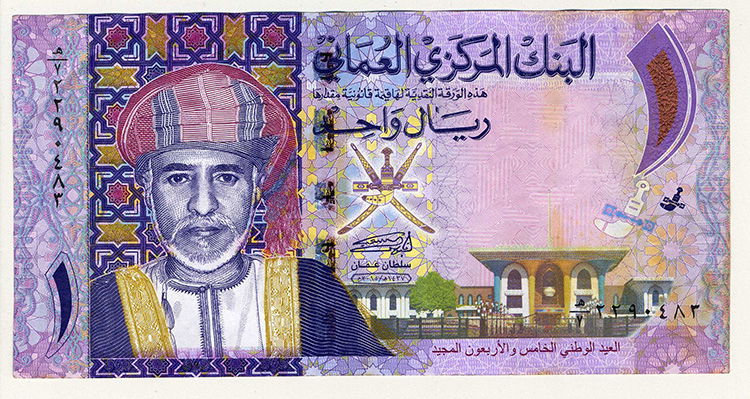

Rubber-stamp democratic institutions, including a legislature, were also formed below the absolute power of the sultan. To lend the legislature credibility it was named Majlis Al-Shura, borrowing the term shura (consultation) from the Ibadhi tradition. In this way, the sultan managed to clothe hereditary sultanic rule in the terminology and symbolism of Ibadhism while maintaining a regime completely opposed to its core principles.

In 1975, for the second time in the 20th century, revolutionary forces were effectively defeated with support from Britain and the shah of Iran. Reforms in education, healthcare and infrastructure cemented the new sultan’s rule as legitimate; a benign despotism guiding Oman through what is now dubbed its ‘renaissance’. The end of the military conflict resolved the larger historical conflict that had lasted for centuries between the divided Omani traditions. While political dissent and opposition existed against sultanic rule in Oman after 1975, it was, and is, scattered in informal networks inside and outside the nation’s borders.

Qaboos bin Said and the Al Alam Palace on an Omani banknote, 2017.

Qaboos bin Said and the Al Alam Palace on an Omani banknote, 2017.

Ultimately the official Omani history of the 20th-century revolutions was written with Qaboos framed as ‘the hand of God’, delivering the people from darkness and evil. Dissident voices at the time of his inauguration wrote about this new state narrative thus:

They present the treachery, theft and exploitation practised by Qaboos and his colonial masters as a wise and correct policy that aims at the progress of the Omani people, and the preservation of its religion and beliefs.

Dissent was ultimately suppressed and history decided. Oman’s 1970s ‘renaissance’ made the impulse for a democratic state, either Ibadhi or socialist, alien and seditious even though its principles had existed at Oman’s beginning. Qaboos’ accession ensured that all Omanis in the modern world would not be citizens of a state, but subjects of a sultan.

James Tarik Marriott is completing a Master’s in Middle East Politics at SOAS.