On October 3, 1935 the forces of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini began their advance upon Ethiopia, known in earlier times as Abyssinia. Italy had long coveted the territory to expand their colonial influence in East Africa. In 1896, Ethiopians had turned back an Italian invasion at Adwa (Adowa), serving as an example of a Black-led country’s defiance of Europe. Taking inspiration from Ethiopia’s long history as an independent Black nation, two Black aviators—Hubert Julian and John C. Robinson—were drawn to Ethiopia by the events of 1935.

Hubert Julian

Hubert Fauntleroy Julian was born in Trinidad a year after the Ethiopian victory at Adwa. He moved to Canada after World War I, where he claims he learned to fly. In 1921, Julian traveled to New York where he found many references to Ethiopia. The Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York City was formed in 1808 by a group of Black members of the First Baptist Church who refused to accept segregated seating. The Mayor of Addis Ababa was among a party of Ethiopian dignitaries welcomed to Harlem in 1919. After Julian met Marcus Garvey, another Caribbean émigré, he joined the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Garvey often used Ethiopia as a metonym for Africa and the official anthem of the UNIA was entitled, “Ethiopia, Thou Land of Our Fathers.”

Julian adopted the title of “Lieutenant Julian of the Royal Canadian Air Force” as he performed parachute stunts, which learning to better fly an airplane from Clarence Chamberlin. Boasting a new nickname, “The Black Eagle of Harlem,” he announced a daring project on January 10, 1924—he would become the first man (Black or White) to fly solo to Africa, a much more dangerous route that than the northern Atlantic flights previously completed. The goal was to leave New York in his Boeing seaplane (acquired with Chamberlin’s assistance) and head south to Brazil. From there he would fly the aspirationally titled Ethiopia I to Liberia (another independent Black nation) with the final destination being Ethiopia.

Julian encountered nothing but trouble on the way to his July 4th flight. He failed to gain the support of the NAACP. His advertisements for funding in Black newspapers attracted the attention of the US government, accusing him of fraud. His investors only released the aircraft to him after additional funds were raised on the spot in the name of Marcus Garvey. The flight itself was a spectacular failure, lasting only five minutes before Julian and Ethiopia I crashed into Flushing Bay.

Julian survived the flight but his transatlantic efforts were soon overshadowed by Charles Lindbergh and Julian’s own legal troubles. But his actions were noted by Ras Tafari, who was to be crowned Emperor of Ethiopia. In April 1930, Tafari sent his cousin, studying at Howard University, a historically Black institution, to request that Julian perform at the Emperor’s coronation. Within a week, Julian was on a ship across the Atlantic.

Tafari had been building an Ethiopian Imperial Air Force with French pilots, paid by the French government; two German Junkers; and a British Gypsy Moth, the newly assembled unflown prize of the collection, a coronation gift from the owners of Selfridge’s department store. Amid tensions with the white pilots, Julian demonstrated his abilities in a Junkers and was rewarded with a commission as a colonel in the air force and the Emperor’s private pilot.

After a trip to New York to drum up American support for Ethiopia with mixed results, Julian returned to Ethiopia for the coronation. During a dress rehearsal for the ceremony, Ethiopian-trained pilots successfully demonstrated their flying abilities in the Junkers planes. Then Julian took to the air in the Emperor’s off-limits prized Gypsy Moth. The crash destroyed not only the plane but Julian’s relationship with Ras Tafari. Julian was already banished and out of the country when Tarafi was crowned Haile Selassie I.

Hubert Julian poses on the wheel of his Bellanca J-2 “Abyssinia” (“Emperor Haile Salassi I King of Kings”, r/n NR-782W) at Floyd Bennett Field, Long Island, New York, circa September 1933. Notation below window reads “Holder World’s Non-Refueling Endurance Record 84 Hrs 33 Mins.” [Partial, cracked glass plate negative.] NASM-XRA-8096

Unbowed, Julian returned to the United States, where he earned his government pilot’s license and formed a Black barnstorming troupe “The Five Black Birds.” He also developed a relationship with aircraft manufacturer Giuseppe M. Bellanca, who refitted a Bellanca J-2 (registration NR-782W). The aircraft had been used by Walter Lees and Frederick Bossy in 1931 to set a new world endurance record for non-refueled flight—84 hours and 32 minutes (not to be broken until the Rutan Voyager in 1986). The aircraft proudly boasted its heritage under the front windows.

Aviator Hubert Julian poses for photographers in front of his Bellanca J-2 at Floyd Bennett Field, Long Island, New York. The aircraft’s propeller is draped with an American flag. Peggy Harding Shannon, holding a bouquet of roses and a bottle of champagne, stands behind Julian on a second chair as a crowd looks on from either side. Date is presumed to be September 29, 1933, when the aircraft was christened “Abyssinia” at a press conference. NASM-XRA-8234

On September 29, 1933 Julian held a press conference at Floyd Bennett Field, New York, christening the plane Abyssinia, Emperor Haile Salassi [sic] I King of Kings and announcing his intentions for another transatlantic flight. But he still needed to pay off the airplane and travelled across the United States and even to London with Amy Ashwood Garvey (Marcus Garvey’s ex-wife) to raise additional funds. By the end of 1934, it did not appear that Julian would attempt his flight anytime soon. (As a footnote, the airplane itself was later sold to the Portuguese Monteverde brothers who wrecked it at Floyd Bennett Field during their June 1935 transatlantic attempt.)

Hubert Julian poses with his Bellanca J-2 “Abyssinia” (“Emperor Haile Salassi I King of Kings”, r/n 782W) on the ground at Floyd Bennett Field, Long Island, New York, 1934. NASM-XRA-3274

John C. Robinson

In 1934, John C. Robinson was contemplating visiting his alma mater, the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, for his 10th reunion and to propose an aviation school there for Black pilots. Robinson, born in Florida and raised in Mississippi, had been one of the first Black pilots to complete his training at the Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical University in Chicago. He and Cornelius Coffey formed the Challenger Air Pilots Association, opened their own airfield, and created an aviation school to support Black pilots.

John C. Robinson’s Chicago business card. Text reads: “J.C. Robinson, U.S. Government Licensed Pilot and Mechanic. Instructor for Aeronautical University, Founded by Curtiss-Wright Flying Service.” NASM-9A16697-018C

Italy made incursions into Ethiopia in late 1934, clearly announcing its intentions. The League of Nations did not act upon Ethiopian appeals in a way that discouraged Italy at all. David Robinson, editor of the Black newspaper the Chicago Defender, wrote in an April 6, 1935 editorial, “News about the dispute between Ethiopia and Italy as published in your neswaper [sic] and also the white papers should bring to our hearts a feeling of sympathy for the last monarchy of our race….Men of our race who are more acquainted with the international sea are faced with a responsibility which stares us in our faces this very hour…we are responsible for the future of our boys and girls who will grow up to find out that they have no chance of existing in a purely dominant white world.”

John C. Robinson’s efforts in Chicago on behalf of Black citizens impressed Haile Selassie’s nephew. After Julian’s time in Africa, the Ethiopians were wary of another American-based pilot, but Robinson’s reputation won them over and he was asked to go to Ethiopia to serve in the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force. Robinson accepted, wanting to prove the mettle of Black pilots, both American and Ethiopian. He stated in a 1936 interview: “I am glad to know that they realize that Ethiopia is fighting not only for herself, but also for black men in every part of the world and that Americans, especially black Americans are willing to anything to help us to carry on and to win.”

In May 1935, Robinson was on his way to Ethiopia. In their first meeting, Haile Selassie offered the American the rank of Colonel in the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force. Robinson also accepted Ethiopian citizenship, so that he could claim dual citizenship and not run afoul of a 19th century law forbidding American citizens to serve in a foreign army when the United States is at peace. He was quickly dubbed “The Brown Condor of Ethiopia.” Robinson found the 1935 Ethiopian Air Force with a few more airplanes and trained pilots than Julian in 1930, but not many. Akaki Field, just outside Addis Ababa, housed a few Potez 25s, a Farman F.192, a couple of Junkers (the same as flown by Julian), and a Fokker F.VII. There were only a few Ethiopian pilots; most of the experienced pilots were still French and would be discouraged from directly supporting war efforts (a 1936 Pittsburgh Courier article even mentioned a Ethiopian woman pilot named Mobin Gretta).

Business card for John C. Robinson, circa 1935. “Col J. C. Robinson, Imperiale Ethiopienne Air Force. Addis Ababa, (Ethiopia).” Imperial standard of Emperor Haile Selassie I, featuring the Lion of Judah, appears in the upper left hand corner. Handwritten inscription to fellow Chicago pilot Dale L. White on lower half of card reads, “To Dale / Say How is the old Chrysler / Hope to get a ride in it again — If I don’t go West / Johnny.” NASM-9A16697-014B

Robinson also found Hubert Julian, who had returned to Ethiopia in April, hoping still to serve Haile Selassie. The Emperor would not permit Julian to rejoin the Air Force, but he restored Julian’s rank of Colonel and assigned him to train employees of the Ministry of Public Works. Julian also appointed himself as a press liaison. Things came to a head on August 9 when Robinson and Julian came to blows in a hotel lobby. The incident was even covered in white newspapers and Julian was immediately stripped of his military command (though he was quietly reinstated and assigned to a far-off outpost). Julian left Ethiopia for good in November 1935, bitter after the loss of stature and additional court intrigue named him in a possible assassination plan against the Emperor.

Robinson continued to serve with the Air Force. His exploits were closely followed by his fellow Black pilots back in Chicago via Black newspapers. According to clippings in Dale White’s Challenger Air Pilots Association scrapbook, six Black aviators began the process to join him in Ethiopia, but were not granted passports. The Pittsburgh Courier published a list of licensed Black fighters acquired from the Negro Affairs Division of the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce. A photo feature on Willa Brown was headlined “Wants to Fight for Ethiopia.”

John Robinson was in the air on October 3, 1935 when the Italians crossed the Mareb River to begin their ground assault on Ethiopia. He was on the ground in Adwa when Italian Capronis bombed the town into rubble, returning to Addis Ababa to report. Italy took the town on October 6, claiming what they could not in 1896.

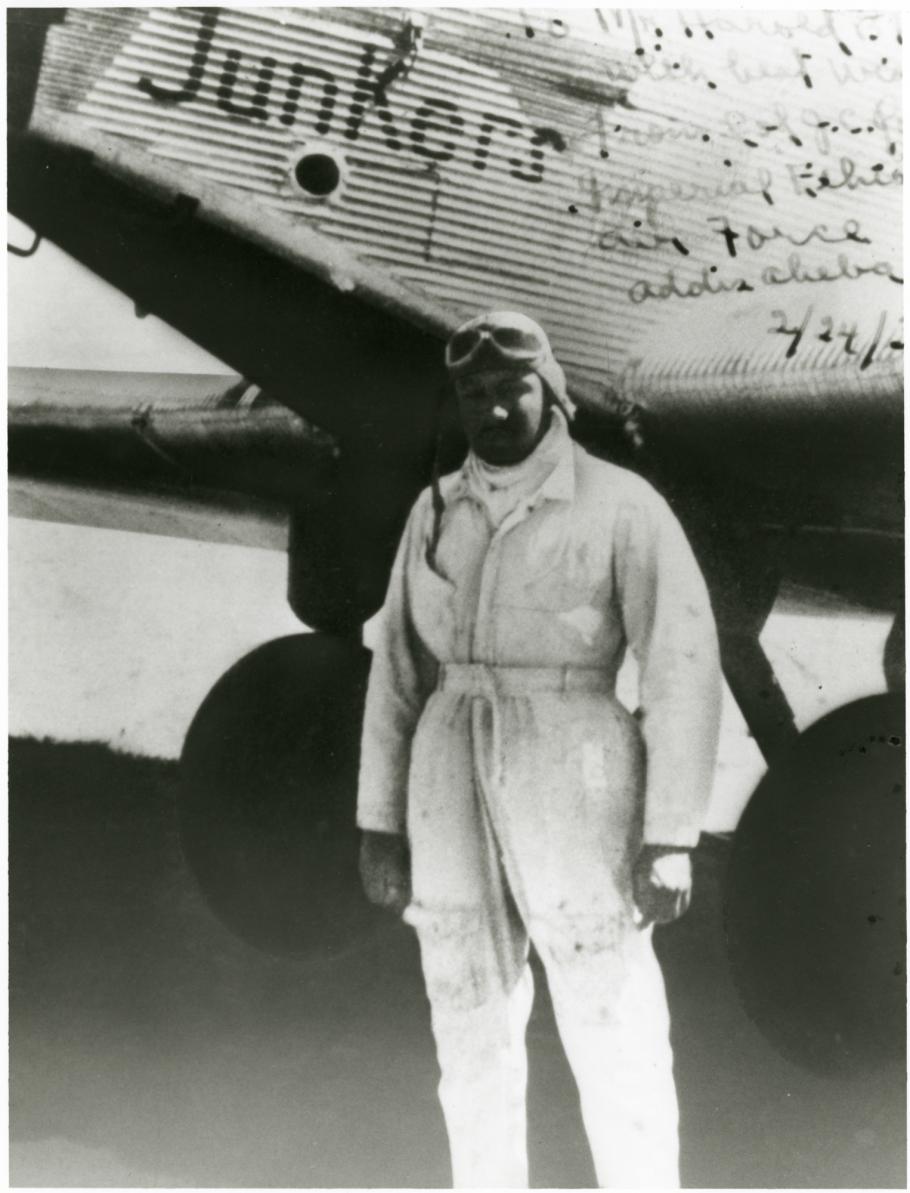

John C. Robinson poses standing in front of nose of a Junkers W 33c, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, circa 1935-6. Inscribed at upper right corner, “To Mr. Harold B. [Hurd] … with best wis[hes] From Col. J. C. Rob[inson]… Imperial Ethio[pian] Air Force, Addis Ababa 2/24/3…” NASM-9A12943

An October 12, 1935 article in the Baltimore Afro-American quoted a letter from Robinson to his fellow Chicago pilots cautioning them to stay where they were: “If we have to face the Italians in our present planes, airworthy though they are, it will be no less than murder….It will be better for you to remain in America and carry on the good work which we have begun in interesting our people in aviation.” He was resolved to stay himself. He was gassed and wounded several times, but continued to fly orders between locations, observe troop movements, and guide Red Cross missions.

Towards the end of April 1936, Robinson took Haile Selassie in a Beech Staggerwing for one last aerial look at Ethiopia. Emperor Haile Selassie fled Addis Ababa on May 2 via train. Robinson flew the Staggerwing to Djibouti where it was impounded. He returned to the United States to acclaim and immediately began his work to develop the aviation school at Tuskegee.

Postscript

Hubert Julian did not return to Ethiopia, but he lived a long life, becoming an arms dealer in Central American and Pakistan under the company name “Black Eagle Associates.” He kept in touch with Giuseppe Bellanca, requesting price quotes for airplanes and sending location updates. Julian ran afoul of the United Nations in the Congo in the 1960s. Although he moved out of the spotlight, he continued to rack up a large file in FBI headquarters until his death in New York in 1983. Although Hubert Julian gained a reputation for self-aggrandizement and empty showmanship, the fact remains that he promoted Ethiopia and supported its continued existence as a Black-ruled sovereign nation.

Emperor Haile Selassie returned to Ethiopia in May 1941. He asked John C. Robinson to join him in rebuilding the Ethiopian Air Force. In 1944, Robinson and five Black pilots and mechanics made their way across war-torn seas to Addis Ababa where they established an aviation training school. Robinson continued to draw on his Chicago aviation ties, helping Ethiopian students attend school in the United States, recommending many to Janet Waterford Bragg. Robinson believed that he was being pushed out by an influx of white Swedish support and was arrested for attacking a Swedish representative. He resigned his commission in 1948. He remained in Ethiopia to work to build Ethiopian Airlines, as he had been instrumental establishing a relationship between Ethiopia and TWA Airlines to send a fleet of DC-3 aircraft and personnel in 1946.

John C. Robinson died in 1954, when he crashed a Stinson L-5 outside of Addis Ababa. His name survives in Ethiopia, including the John C. Robinson American Center at the National Archives and Library Agency in Addis Ababa.

Additional Resources

Bellanca, Giuseppe M. Collection, Acc. NASM.1993.0055, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

Black Wings Exhibit and Book Collection. Acc. NASM.1993.0060. National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

Caprotti, Federico. “Visuality, Hybridity, and Colonialism: Imagining Ethiopia Through Colonial Aviation, 1935–1940.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101, no. 2 (2011): 380-403. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27980183.

Featherstone, David. “Black Internationalism, Subaltern Cosmopolitanism, and the Spatial Politics of Antifascism.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103, no. 6 (2013): 1406-420. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24537559.

Federal Aviation Administration Aircraft Registration Files, Acc. NASM.XXXX.0512, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

Frebert, George J. Delaware Aviation History. Dover, DE: Dover Litho, 1998.

Julian, Hubert F. Black Eagle: Colonel Hubert Julian, as told to John Bulloch. London: Adventurers Club, 1965.

Nugent, John Peer. The Black Eagle. New York: Stein and Day, 1971.

Shack, William A. “Ethiopia and Afro-Americans: Some Historical Notes, 1920-1970.” Phylon (1960-) 35, no. 2 (1974): 142-55. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/274703.

Shaftel, David. “The Black Eagle of Harlem.” Air & Space Magazine, December 2008. Accessed January 22, 2021. https://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/the-black-eagle-of-harlem-95208344/?all.

Simmons, Thomas E. The Man Called Brown Condor: The Forgotten History of an African American Fighter Pilot. New York: Skyhouse, 2013.

Weisbord, Robert G. “Black America and the Italian-Ethiopian Crisis: An Episode in Pan-Negroism.” The Historian 34, no. 2 (1972): 230-41. Accessed January 22, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24442848.

White, Dale L., Sr., Papers Collection, Acc. NASM.2013.0050, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. https://sova.si.edu/record/NASM.2013.0050.