For the second time in nine months, Col Assimi Goïta has seized power in Mali, detaining transitional President Bah Ndaw and Prime Minister Moctar Ouane after accusing them of failing in their duties and trying to sabotage the West African state’s transition to democracy.

He also led the coup which deposed the elected head of state, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, on 18 August last year.

But the 2020 coup was widely welcomed by the public and opposition politicians who had become exasperated with Mr Keïta’s feeble leadership and tolerance of corruption.

It took weeks of negotiation before the terms for a transition back to democratic rule were finally agreed between the coup leaders and mediators from the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), the regional bloc to which Mali belongs.

Col Goïta was installed as transitional vice-president – a recognition of the army’s still powerful influence. An 18-month deadline was agreed for presidential and parliamentary elections to be held.

But resolving the conundrum posed by this latest military intervention – which began when soldiers arrested Mr Ndaw and Mr Ouane on Monday – could prove rather more awkward for Ecowas, whose chief mediator, Nigeria’s former President Goodluck Jonathan, is in Mali to resolve the crisis.

There is much less time. Elections are scheduled in nine months and much-needed constitutional changes have yet to be agreed, legislated by the nominated transitional assembly or approved by the public in a referendum.

And the mood on the streets is different. Last year the public was disillusioned with Mr Keïta and hungry for change. But there is no such popular animosity towards Mr Ouane, who only fills an interim role. Civil society groups condemned the latest putsch.

Threat of sanctions

Moreover, regional and international trust in Col Goïta has been shattered by this week’s events – which have been met with ferocious condemnation, with the European Union (EU) already threatening sanctions.

The deal negotiated last year between the military and Ecowas was based on an understanding that, although the army’s influence would be tacitly acknowledged through the appointment of soldiers to several key posts, the transition would be civilian-led, albeit by Mr Ndaw, a former minister and retired officer.

Mali began to edge forward. There were still serious problems – hardly a surprise in a country struggling to contain jihadist attacks across the far north and broker local deals to end inter-communal violence between farming and herding communities in its central regions.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTAFP

IMAGE COPYRIGHTAFPThere were complaints about the performance of the transitional government, while opposition political parties felt they had been marginalised.

However, Mr Ouane drafted an ambitious programme of planned reforms designed to prepare for the restoration of a normal functioning democratic system.

He began to address the problems – such as decentralisation – that had often been neglected by Mr Keïta.

Action did sometimes fall short of words. But there was a sense of method and direction; if anything, in the view of some sceptics, the premier’s plans for what could be achieved during the transition were over-ambitious.

Yet, now, all this has been thrown into question. Trust in Col Goïta’s commitment to the transition to free elections – already shaken by rumours that he might have his own election ambitions – has been badly damaged.

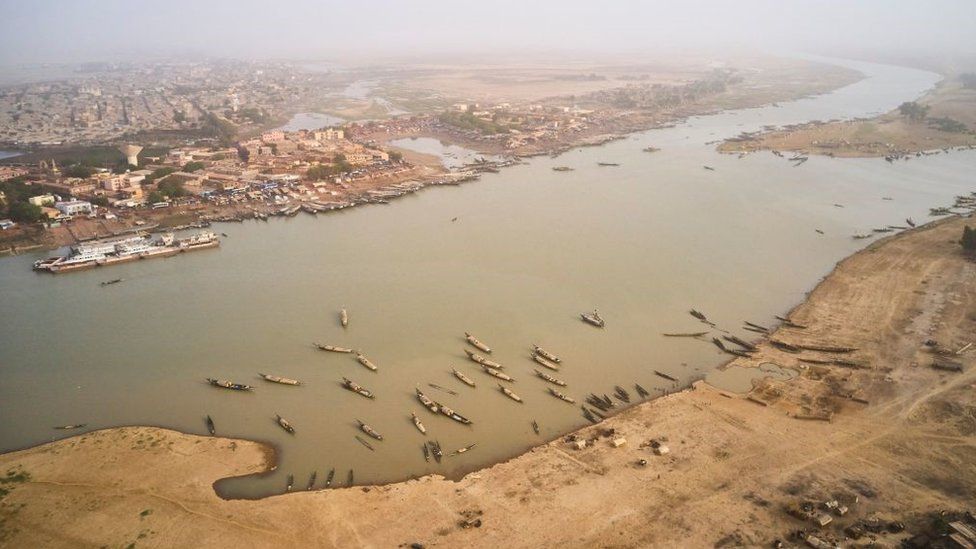

For the second time in less than a year, leaders of Mali’s government were taken into custody at the barracks in Kati, the garrison town just the other side of the hills from Bamako.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTAFP

IMAGE COPYRIGHTAFPIt is almost as if the bar for military intervention has become progressively lower.

In March 2012, discontented mutineers seized power after a wave of fury over a sense that ordinary soldiers had been left alone to suffer, and die, in the face of jihadist attacks in the Sahara desert, while the hierarchy sat safe in Kati and Bamako.

That putsch too was eventually unravelled through negotiations leading to the installation of a fragile civilian interim administration.

Last year, the draining pressure of the by now lengthy conflict with jihadists played a role. But frustration with Mr Keïta was a bigger factor, with mass demonstrations on the streets of the capital, Bamako.

This time, the military grievance is the removal of two ex-putschists from ministerial posts and their replacement by more establishment senior officers.

The army, or at least those around Col Goïta, appear increasingly assertive in their assumed right to set the terms of transition to protect their own interests, political and economic.

‘Fight against jihadists risk being undermined’

And so, for the second time in less than a year, Mr Jonathan finds himself in the Malian capital, trying to convince the men in military fatigues that power must be restored to civilians – and trying to get them to understand why West African governments, and the international community, will not be prepared to recognise a putchist regime.

And if this argument cannot be won, what then?

Blanket economic sanctions on Mali would cause severe pain for the population and serious disruption to an economy already hurt by the long-running security crisis and by the pandemic.

Yet would targeted sanctions aimed at a few coup leaders really have much effect?

Moreover, if Mali is governed by a regime that is not internationally recognised as legitimate, that could severely hamper collaboration between the Malian army and the French and other European military forces now deployed in the country in operations against the jihadists.

Mr Jonathan knows that Ecowas has the full backing of the African Union, the EU, the US, and the UN, but he has some difficult judgements to make in his efforts to resolve the crisis.

Action that looks punitive towards Mali as a whole could allow the military to stir up nationalist feelings and paint Ecowas as outsider bullies.

But a retreat that appears to concede to Col Goïta will only confirm military control over the transition and potentially jeopardise hopes for a credible democratic election process early next year.

It will require skilled diplomacy to find a face-saving exit from this week’s conundrum, one that accommodates military pressures and yet somehow saves the political transition and the route back to meaningful constitutional democratic rule.