Alan Macleod uncovers the deep links between the British security state and the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, responsible for training a large number of British, American, and European agents and defense analysts.

LONDON — Last week, MintPress exposed how the supposedly independent investigative collective Bellingcat is, in fact, funded by a CIA cutout organization and filled with former spies and state intelligence operatives. However, one part of the story that has remained untold until now is Bellingcat’s close ties to the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, an institution with deep links to the British security state and one that trains a large number of British, American and European agents and defense analysts.

A school for spooks

A prestigious university located in the heart of London, King’s College has, in its own words, “a number of contracts and agreements with various departments within government, including the Cabinet Office, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and the Ministry of Defence.” Some of those contracts are up to 10 years long. The university has so far refused to elaborate on the agreements, telling investigative news outlet Declassified UK that doing so could undermine U.K. security services.

A 2009 study published by the CIA spoke approvingly of how beneficial it can be to “use universities as a means of intelligence training,” noting that, “exposure to an academic environment, such as the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, can add several elements that may be harder to provide within the government system.” The paper, written by two King’s College staffers, is essentially a request to the agency to send more of its recruits there, and boasts about how the department’s staff have “extensive and well-rounded intelligence experience” and how their programs “offer a containing space in which analysts from every part of the community can explore with each other the interplay of ideas about their profession.”

In 2013, former CIA Director Leon Panetta took time out of his schedule as then-secretary of defense to visit the Department of War Studies, where he expressed his profound gratitude to the unit. “I deeply appreciate the work that you do to train and to educate our future national security leaders, many of whom are in this audience,” he said, before adding that it was those young leaders who must ensure that NATO had the creativity, innovation and the commitment to develop and share capabilities in order to meet future security threats, citing the need to expand into tech, surveillance and cyberwarfare.

Former CIA head Leon Panetta exits King’s College after giving a speech in 2013. Photo | DVIDS

It was this department that Bellingcat founder Eliot Higgins joined in 2018 as visiting research associate, with Bellingcat maintaining a close relationship with it to this day.

After studying their writers’ backgrounds, MintPress can confirm that no fewer than six Bellingcat employees or contributors — including Cameron Colquhoun, Jacob Beeders, Lincoln Pigman, Aliaume Leroy, Christiaan Triebert and senior investigator Nick Waters — all pursued postgraduate studies within the department, the most popular being the “Conflict, Security and Development” degree overseen by Professor Mats Berdal.

For 13 years, Professor Berdal was employed by the Norwegian Defence University College, Norway’s version of West Point. Berdal is one of a host of King’s College War Studies academics who previously taught there, including one who continues to be an officer in the Norwegian Armed Forces, serving in multiple NATO conflicts in the Middle East.

While many in the West picture Norway as a peaceful, enlightened nation, the country is actually a key driving force within NATO; former Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg is the organization’s current secretary general. Sending troops and other assistance, it was the U.S.’ partner in attacks on Kosovo, Afghanistan and Libya. Norway has among the highest per capita military spending in Europe and is one of the minority of NATO members to exceed the defense spending benchmark of 2% of GDP.

A network of pro-war think tanks

Before joining King’s College, Professor Berdal was Director of Studies at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), one of the world’s most influential think tanks. Also situated in central London, the organization is directly funded by NATO and its member states, as well as by major weapons manufacturers such as Airbus, BAE Systems, Boeing and Raytheon. In 2016, the IISS was the subject of a major scandal after it was found to have secretly accepted £25 million — around $34 million — from the government of Bahrain.

Founded in 1958, the IISS provided much of the intellectual basis behind the Cold War scaremongering around Soviet military capacity, thereby pushing NATO members to spend more on arms. On its advisory board are a former NATO secretary general, the former chief of defense intelligence for the Israeli Defense Forces, and, until recently, the CEO of Lockheed Martin. Today, the think tank is a major driver in the increasing hostility towards China, Russia and North Korea. A number of other current Department of War Studies academics have held positions at the IISS as well. Indeed, King’s College boasts that one of the “key benefits” of studying there is its “established links” with the IISS.

A second pro-war think tank with which King’s College prides itself on working closely is the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI). RUSI’s funding comes from many of the same sources as the IISS’s. Its senior vice president is retired American General David Petraeus and its chairman is Lord Hague, Britain’s secretary of state from 2010 to 2015.

A host of King’s College academics — including Jack Spence, Benedict Wilkinson, Brian Holden-Reid, Walter Ladwig, Thomas Maguire and Neil Melvin — have also held positions at RUSI. Perhaps the most notable King’s College-RUSI crossover is Professor Sir David Omand, who was formerly the think tank’s vice president, as well as the head of GCHQ, Britain’s version of the NSA.

Source | RUSI

Bellingcat writer Dan Kaszeta is an associate fellow at the organization. Bellingcat, RUSI and King’s College often cite each other in papers and reports, providing something of a united front on controversial issues of statecraft.

One man who links the IISS and RUSI together is Professor Sir Lawrence Freedman, a key member of the Department of War Studies who went on to become King College’s vice principal. A powerful figure in British politics, Freedman contributed to Prime Minister Tony Blair’s 1999 speech in which he established the Blair Doctrine, a maxim that NATO could and should militarily intervene anywhere in the world to stop human rights violations.

A rogues’ gallery

For an institution that prides itself on cultivating independent thought, there exists a remarkable overlap between the staff of the Department of War Studies and the innermost halls of power of the British state. Professor John Gearson, for example, was principal defence policy adviser to the Defense Select Committee at the House of Commons, a senior adviser to the Ministry of Defense, and taught terrorism and asymetric warfare to military officers at the U.K. Defense Academy.

Another professor, Michael Goodman, is a current British Army reservist and formerly the Official Historian of the Joint Intelligence Committee (a body that oversees Britain’s intelligence organizations).

Visiting professors include Paul Rimmer, who was deputy chief of defence intelligence until last year; Lord Robertson, who was secretary general of NATO at the time of the Afghanistan invasion; and Sir Malcolm Rifkind, the former minister of defense. The longtime cabinet member was the creator of the Rifkind Doctrine — the controversial British policy on nuclear weapons. Rifkind rejected the idea that the country should use atomic missiles only as a last resort after being attacked, insisting that he could also use them simply to “deliver an unmistakable message of Britain’s willingness to defend her vital interests.”

King’s College visiting fellow Vera Michlin-Shapir moderates a panel in Tel Aviv on the future of post-war Syria. Photo | INSS

It is not just British officials who teach King’s College students, however. Christopher Kolenda, for instance, was commander of an 800-man strong U.S. task force in Afghanistan, where he “pioneered innovative approaches to counterinsurgency” according to his bio at the hawkish think tank the Center for New American Security (CNAS), where he is a senior fellow. CNAS recently released a report calling for more “innovative” use of what it called “coercive economic statecraft,” (i.e., sanctions) and continues to saber rattle against China and Russia.

Between 2009 and 2010, Kolenda was a strategic advisor to COMISAF, the Commander of International Security Assistance Force. In plain English, he provided some of the brains behind the occupation of Afghanistan. Before pursuing a role in academia, he was also a senior advisor to Undersecretary of Defense Michele Flournoy and three 4-star generals. Flournoy was President Joe Biden’s first choice to run the Pentagon.

The department also contains a number of Israeli academics, including Vera Michlin-Shapir, a former official in her country’s National Security Council who worked in the prime minister’s office. Meanwhile Ofer Fridman served as an officer in the IDF between 1999 and 2011, during which time it was carrying out some of its worst war crimes against Palestine and Lebanon. After leaving the IDF, Fridman became an arms dealer, becoming the head of non-lethal weapons at LHB Ltd., which describes itself as “the leading company in Israel for security and defense advanced solutions.” In 2016, King’s College also hosted a lecture by the former head of Shin Bet, the Israeli secret police force.

The department has links to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as well, with one senior research fellow, Nawaf Obaid, a former special advisor to the Saudi Ambassador in the U.K. and Ireland and a consultant at the Royal Court in Riyadh.

Weapons spending good, Russia bad.

While the department’s staff are concerning enough, much of King’s College academic output is even more troubling, and appears to be completely in line with that of NATO and weapons contractors. One study named “A benefit, not a burden: The security, economic and strategic value of Britain’s defence industry,” for instance, reads like a press release from Raytheon, extolling how many people the industry employs. The report claimed that remaining one of the world’s top arms manufacturers was crucial in “build[ing] a secure and resilient U.K. and to help shape a stable world.” “Without a vibrant and thriving domestic defence industrial base,” it warned, “there is a risk that the U.K. will jeopardise its freedom to act in an unstable, fast-changing world,” concluding that the government should protect or “ideally expand” its defense spending budget.

A report from last August also lobbied the government to invest in making the United Kingdom a “leading nation for space.” “Investment in space surveillance capacity is key to seizing the commercial and diplomatic opportunities offered by space while defending U.K. economic and security interests,” it concludes. Surprisingly, the report insists that it would take only a “modest investment” from the government to turn Great Britain into a leading force in a rapidly expanding market.

King’s College also published a study, titled “The future strategic direction of NATO,” advising that the organization “urgently needs a coherent policy on China” and that it must re-up its commitment to countering Russia. It recommends that the majority of member states increase their military budgets and that they must “share the burden of responsibility on nuclear weapons” by allowing the U.S. to store missiles inside their territories.

Meanwhile, their 2018 report “Weaponizing news: RT, Sputnik and targeted disinformation” analyzes Russian state-backed media outlets and accuses them of carrying out a campaign of “information-psychological warfare” over its coverage of contentious events such as the alleged Skripal poisoning and the wars in Ukraine and Syria. The report claims Russian media is turning news into a weapon by projecting an image of strength and stability while highlighting flaws in Western democracies. While praising the work of Bellingcat and disinfo outlet “Prop or Not,” it concludes by advising that the West must “use technical means to prevent propaganda.”

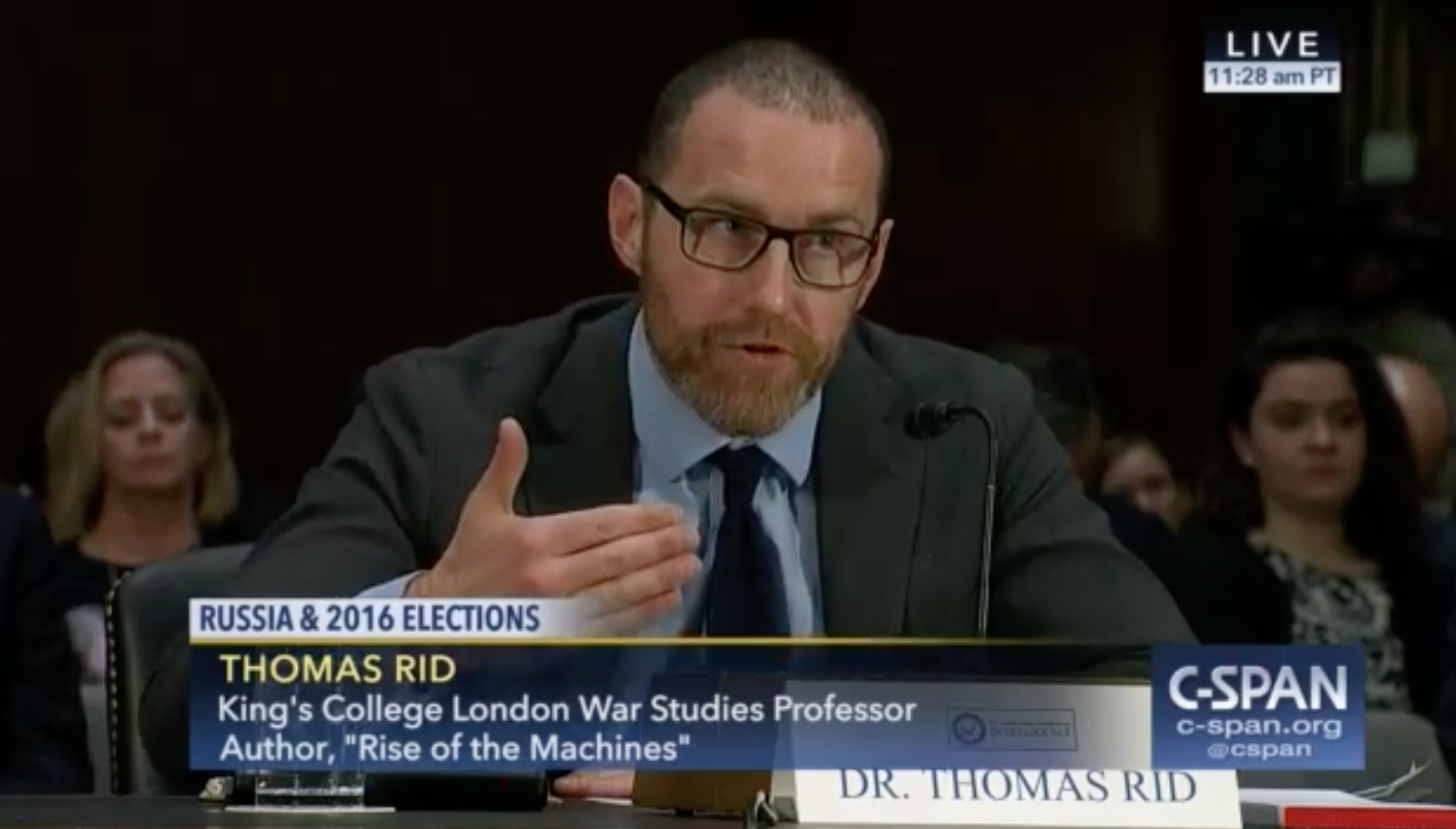

King’s College professor Thomas Rid testifies before a Senate committee on Russian meddling. Photo | CSPAN

These technical solutions, we now know, have largely entailed NATO indirectly taking control of social media. In 2018, Facebook announced that NATO’s cutout organization, the Atlantic Council, was becoming its “eyes and ears,” giving it significant control over curating its news feed, supposedly in an attempt to limit disinformation. Yet many of the most lurid stories around RussiaGate were started by the Council itself, which pumped out report after report accusing virtually every political movement in Europe outside the establishment beltway as being the “Kremlin’s Trojan Horses.”

King’s College staff have also been crucial in propagating the idea of Russian interference in American politics, with Professor Thomas Rid testifying before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on the “dark art” of Russian meddling, and condemning WikiLeaks and alternative media journalists as unwitting agents of disinformation. Rid previously described 2016 as the “biggest election hack in U.S. history.”

Earlier this year, Facebook also hired former NATO press officer and Atlantic Council Senior Fellow Ben Nimmo as head of its intelligence team. Meanwhile Reddit appointed former Atlantic Council Deputy Director of Middle Eastern Strategy Jessica Ashooh as its head of policy. And Eliot Higgins, of course, was a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council as well. In recent years, social media giants like Facebook and Google have radically altered their algorithms, demoting content from adversarial nations, but also attacking alternative media that challenge the power of NATO and the national security state.

Today, the Department of War Studies hosted an online seminar with two senior NATO officials who discussed what they saw as Russia and China’s increasingly aggressive actions, as well as new ways in which NATO can secure its control over the internet.

A military-academic-journalistic nexus

What is being described is a network of military, think-tank and media units all working towards furthering the goals of the national security state. Bellingcat regularly holds seminars and courses at King’s College, teaching the next generation of state officials how to use big-data and surveillance tools.

While King’s College provides an academic veneer for the national security state, Bellingcat provides a journalistic one. This cluster of think tanks, academic reports, and newsy investigative articles all cite one another as credible, independent sources when, in reality, they are all part of the same network furthering an agenda. It should be noted that this was an investigation into just one department in one school in one college of the University of London. The links to the highest levels of power were so profound and so manifold that it often seemed harder to find someone in the department who was not linked to military or intelligence communities. Thus, one could be forgiven for mistaking the Department of War Studies for a department of war mongers.

Feature photo | Photo by King’s College. Editing by MintPress News

Alan MacLeod is Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.