Sincere internal criticism of the U.S. — or any country — often sounds a lot like insincere foreign criticism.

A MINOR SQUALL on Twitter this past week may have largely gone unnoticed amid the larger hurricane about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But it’s worth taking a close look at it, because it illustrates something significant about U.S. foreign policy since World War II, and how propaganda works everywhere.

It started when Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs — the equivalent to the U.S. State Department — did something unusual: It tweeted out an endorsement of a 2014 article in Foreign Affairs — the publication of the Council on Foreign Relations, probably the most influential American think tank on U.S. foreign policy. The piece was by John Mearsheimer, a professor in the political science department at the University of Chicago and a prominent member of the “realist” school of foreign policy thought. You can understand why the Russian government liked it, because it was called “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault.”

This led to a response from Anne Applebaum, a neoconservative journalist who’s currently a staff writer at The Atlantic. “Now wondering if the Russians didn’t actually get their narrative from Mearshimer et al.,” she wrote. “Moscow needed to say West was responsible for Russian invasions (Chechnya, Georgia, Syria, Ukraine), and not their own greed and imperialism. American academics provided the narrative.”

The “et al” part is important here. In U.S. political lore NATO was created in 1949 as a defensive military alliance against the Soviet Union and its allies. The reality was somewhat different. But for realists in general, not just Mearsheimer, the Soviet collapse and the end of the Cold War meant that an expansion of NATO could lead to dangerous conflict with Russia. Fifty American foreign policy leaders, largely realists, wrote to President Bill Clinton in 1997 that pushing NATO’s borders eastward would be “a policy error of historic proportions. We believe that NATO expansion will decrease allied security and unsettle European stability … In Russia, NATO expansion, which continues to be opposed across the entire political spectrum, will strengthen the nondemocratic opposition, undercut those who favor reform and cooperation with the West, bring the Russians to question the entire post-Cold War settlement, and galvanize resistance in the Duma …”

To comprehend Applebaum’s glee here, her tweet should be seen as not just about Ukraine, but as part of a decades-long battle between realists and neoconservatives. And her rhetorical gambit is a favorite of neoconservatives, one they’ve used many times before and will surely use many times again. Neither the realists or neoconservatives are any great shakes from a progressive perspective, but you have to understand them to understand U.S. foreign policy.

Realists believe that the U.S. should run as much of the world as possible, while being mindful that there are limits to American power and remember other countries (in particular, “great powers” like Russia and China) have their own interests. For realists, morality, democracy, the sovereignty of small countries, etc., are nice in theory — but it’s naïve to think they can ever play much role in great power politics.

For instance, in Mearsheimer’s 2014 article, he wrote that “it is the Russians, not the West, who ultimately get to decide what counts as a threat to them.” But of course the same thing could have been written about the U.S. before the invasion of Iraq. From a realist perspective, the only question about that war was whether it was wise or foolish for U.S. power, not whether it was right or wrong.

Likewise, in a recent interview with Mearsheimer in the New Yorker, Isaac Chotiner brought up the long history of ugly U.S. actions in the Western Hemisphere, and remarked, “We’re essentially saying that we have some sort of say over how democratic countries run their business.” Mearsheimer replied with equanimity, “We do have that say, and, in fact, we overthrew democratically elected leaders in the Western hemisphere during the Cold War because we were unhappy with their policies. This is the way great powers behave.”

What makes propaganda propaganda is often not its lack of factual basis, but its bad faith.

Then there are the neoconservatives. The term “neoconservatism” wasn’t coined until the 1970s, but it arguably has its roots in the desire of one U.S. foreign policy faction after World War II to confront the Soviet Union and reverse the communist revolution in China. Neoconservatives believe the U.S. can and must run the entire world, and justify the necessary wars with intense sloganeering about our devotion to democracy and human rights. This is sincerely felt by some neoconservatives, in the same way there were Soviet apparatchiks who were sincerely angry about the oppression of African Americans in the U.S. But the practical effect of this sentiment is near-zero: When the rubber meets the road, neoconservatives usually have no problem supporting the most vicious dictatorships if it serves their larger goals, and spend little energy fretting about democracy and human rights in America.

Neither school has much concern for basic justice or the lives of regular, non-powerful people. But the realists at least tend to be more tethered to the world we live in, while the neoconservatives consistently succumb to bizarre fantasies of omnipotence that lead to catastrophe. (There is arguably a third school that embraces an 1821 admonition from John Quincy Adams that America “goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.” But it’s so weak that for practical purposes it’s irrelevant.)

In any case, Applebaum’s attack on Mearsheimer — that his analysis sounds similar to Russian propaganda, or even inspired it in the first place — is the kind of ugly, childish rhetoric in which neoconservatives specialize. For neoconservatives, if any external criticism of the U.S. is similar to internal criticism from Americans, that immediately discredits the internal critics. That argument seems to make sense until you think about it for two seconds. The fact is that when countries engage in propagandistic attacks on others, it’s rarely all lies. Indeed, propaganda often contains a surprisingly high percentage of truth. That’s because powerful nations are constantly doing terrible things, so other powerful governments don’t always have to make things up to criticize them.

What makes propaganda propaganda is often not its lack of factual basis, but its bad faith. In this particular case, Mearsheimer was correct that “the West had been moving into Russia’s backyard and threatening its core interests.” Meanwhile, Putin has been vociferously making the same complaints for years. But obviously Russia doesn’t object to a country moving into another’s backyard on principle. Just ask anyone who lives in Aleppo.

Likewise, in 2006 when Iran’s then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad sent a long letter to George W. Bush, his indictment of the U.S. was mostly on point — and indeed sounds a lot like criticism from America’s left. Yet Ahmadinejad’s words about the injustice of our treatment of prisoners at Guantánamo Bay did not carry great moral weight, since you could just go to Evin Prison to find how much Ahmadinejad’s own government actually cares about the brutal detention of human beings.

From the other direction, consider the attacks of Alexey Navalny, a prominent Russian opposition leader currently in prison, on Vladimir Putin’s war:

What Navalny says is generally true. And when he speaks about “the aggressive war against Ukraine” and the fact “Putin is not Russia” it also sounds a lot like the criticisms U.S. officials make in bad faith against Russia. But this does not invalidate what Navalny is saying — even though Applebaum’s equivalents in Russia have surely claimed that it does. (And like Mearsheimer, Navalny is by no means a progressive hero.)

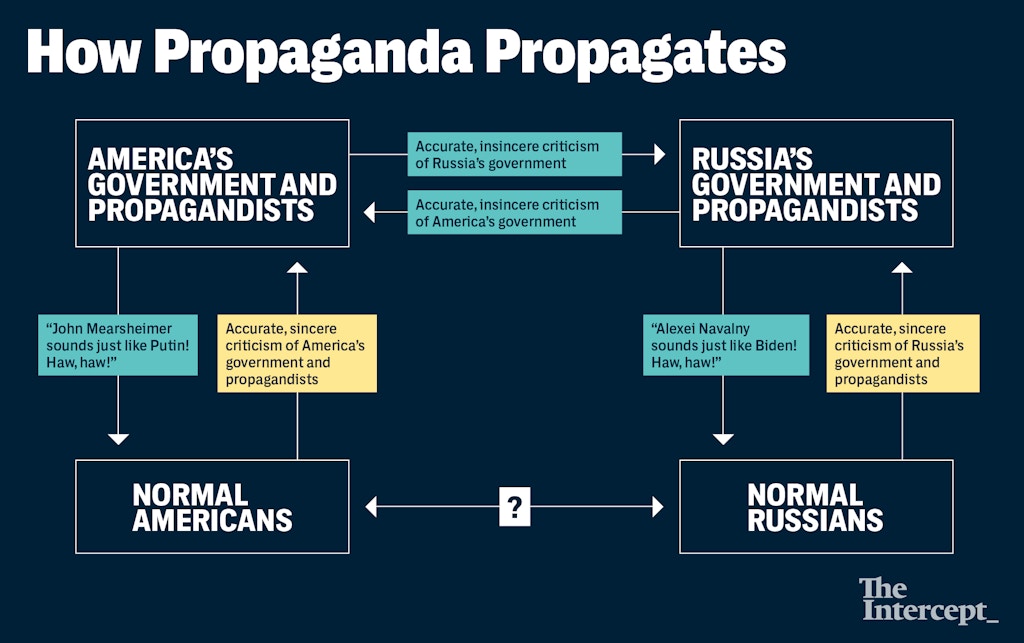

The lesson here is straightforward: Everyone who wants their country to improve should feel free to engage in sincere, accurate criticism of their government’s actions. It is both inevitable and irrelevant that it will likely end up sounding similar to criticism of their country by foreign “enemy” governments. And those who claim the similarity discredits the internal critics should be ignored like the propagandists they are. To keep this in mind, you can memorize this article, or just keep a copy of this chart handy: