Russia is no longer fighting a Ukrainian army equipped by NATO, but a NATO army manned by Ukrainians. Yet, Russia still holds the upper hand despite its Kharkiv setback.

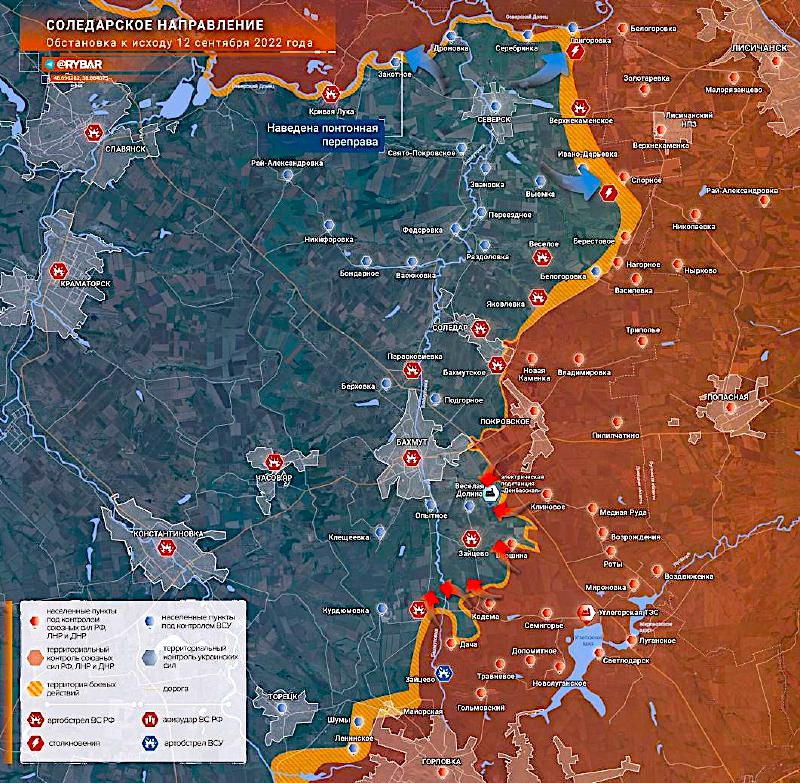

The Ukrainian army began a major offensive against Russian forces deployed in the region north of the southern city of Kherson on Sept. 1. Ten days later, the Ukrainians had expanded the scope and the scale of its offensive operations to include the region around the northern city of Kharkov.

While the Kherson offensive was thrown back by the Russians, with the Ukrainian forces suffering heavy losses in both men and material, the Kharkov offensive turned out to be a major success, with thousands of square kilometers of territory previously occupied by Russian troops placed back under Ukrainian governmental control.

Instead of launching its own counteroffensive against the Ukrainians operating in the Kharkov region, the Russian Ministry of Defense (MOD) made an announcement many people found shocking: “To achieve the stated goals of a special military operation to liberate the Donbass,” the Russians announced via Telegram, “it was decided to regroup Russian troops…to increase efforts in the Donetsk direction.”

Downplaying the notion of a retreat, the Russian MOD declared that “to this end, within three days, an operation was carried out to curtail and organize the transfer of [Russian] troops to the territory of the Donetsk People’s Republic.

During this operation,” the report said, “a number of distractions and demonstration measures were carried out, indicating the real actions of the troops” which, the Russians declared, resulted in “more than two thousand Ukrainian and foreign fighters [being] destroyed, as well as more than a hundred units of armored vehicles and artillery.”

To quote the immortal Yogi Berra, it was “déjà vu all over again.”

Phases of the War

Russian bombardment of telecommunications antennas in Kiev, March 1, 2022. (Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine/Wikimedia Commons)

On March 25, the head of the Main Operational Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, Colonel General Sergei Rudskoy, gave a briefing in which he announced the end of what he called Phase One of Russia’s “special military operation” (SMO) in Ukraine.

The goals of the operation, which had begun on Feb. 24 when Russian troops crossed the border with Ukraine, were to cause “such damage to military infrastructure, equipment, personnel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine” to pin them down and prevent any significant reinforcement of the Ukrainian forces deployed in the Donbass region.

Rudskoy then announced Russian troops would be withdrawing and regrouping so that they will be able to “concentrate on the main thing — the complete liberation of Donbass.”

Thus began Phase Two.

On May 30 I published an article in Consortium News where I discussed the necessity of a Phase Three. I noted that

“both Phase One and Phase Two of Russia’s operation were specifically tailored to the military requirements necessary to eliminate the threat posed to Lugansk and Donetsk by the buildup of Ukrainian military power in eastern Ukraine. … [A]t some point soon, Russia will announce that it has defeated the Ukrainian military forces arrayed in the east and, in doing so, end the notion of the imminent threat that gave Russia the legal justification to undertake its operation.”

Such an outcome, I wrote, would “leave Russia with a number of unfulfilled political objectives, including denazification, demilitarization, permanent Ukrainian neutrality, and NATO concurrence with a new European security framework along the lines drawn up by Russia in its December 2021 treaty proposals. If Russia were to call a halt to its military operation at this juncture,” I declared, “it would be ceding political victory to Ukraine, which ‘wins’ by not losing.”

Donate to CN’s 2022 Fall Fund Drive

This line of thinking was predicated on my belief that “[w]hile one could have previously argued that an imminent threat would continue to exist so long as the Ukrainian forces possessed sufficient combat power to retake Donbass region, such an argument cannot be made today.”

In short, I believed that impetus for Russia expanding into a third phase would arise only after it completed its mission of liberating the Donbass in Phase Two. “Ukraine,” I said, “even with the massive infusion of military assistance from NATO, would never again be in a position to threaten a Russian conquest of the Donbass region.”

I was wrong.

Anne Applebaum, a neoconservative staff writer for The Atlantic, recently interviewed Lieutenant General Yevhen Moisiuk, the deputy commander in chief of the Ukrainian armed forces, about the successful Ukrainian offensive operation. “What really surprises us,” Moisiuk said, “is that the Russian troops are not fighting back.”

Applebaum put her own spin on the general’s word. “Offered the choice of fighting or fleeing,” she wrote of the Russian soldiers, “many of them appear to be escaping as fast as they can.”

According to Applebaum, the Ukrainian success on the battlefield has created a new reality, where the Ukrainians, she concludes, “could win this war” and, in doing so, bring “about the end of Putin’s regime.”

I wasn’t that wrong.

Soviet and NATO Doctrine

Russian military vehicles bombed by Ukrainian forces, March 8, 2022. (Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine/Wikimedia Commons)

War is a complicated business. Applebaum seems ignorant of this. Both the Ukrainian and Russian militaries are large, professional organizations backed by institutions designed to produce qualified warriors. Both militaries are well led, well equipped, and well prepared to undertake the missions assigned them. They are among the largest military organizations in Europe.

The Russian military, moreover, is staffed by officers of the highest caliber, who have undergone extensive training in the military arts. They are experts in strategy, operations, and tactics. They know their business.

For its part, the Ukrainian military has undergone a radical transformation in the years since 2014, where Soviet-era doctrine has been replaced by a hybrid one that incorporates NATO doctrine and methodologies.

This transformation has been accelerated dramatically since the the Russian invasion, with the Ukrainian military virtually transitioning from older, Soviet-era heavy equipment to an arsenal which more closely mirrors the organization and equipment of NATO nations, which are providing billions of dollars of equipment and training.

The Ukrainians are, like their Russian counterparts, military professionals adept at the necessity of adapting to battlefield realities. The Ukrainian experience, however, is complicated by trying to meld two disparate doctrinal approaches to war (Soviet-era and modern NATO) under combat conditions. This complexity creates opportunities for mistakes, and mistakes on the battlefield often result in casualties — significant casualties.

Russia has fought three different styles of wars in the six months since it entered Ukraine. The first was a war of maneuver, designed to seize as much territory as possible to shape the battlefield militarily and politically.

The operation was conducted with approximately 200,000 Russian and allied forces, who were up against an active-duty Ukrainian military of some 260,000 troops backed by up to 600,000 reservists. The standard 3:1 attacker-defender ratio did not apply — the Russians sought to use speed, surprise, and audacity to minimize Ukraine’s numerical advantage, and in the process hoping for a rapid political collapse in Ukraine that would prevent any major fighting between the Russian and Ukrainian armed forces.

This plan succeeded in some areas (in the south, for instance, around Kherson), and did fix Ukrainian troops in place and caused the diversion of reinforcements away from critical zones of operation. But it failed strategically — the Ukrainians did not collapse but rather solidified — ensuring a long, hard fight ahead.

The second phase of the Russian operation had the Russians regroup to focus on the liberation of Donbass. Here, Russia adapted its operational methodology, using its superiority in firepower to conduct a slow, deliberate advance against Ukrainian forces dug into extensive defensive networks and, in doing so, achieving unheard of casualty ratios that had ten or more Ukrainians being killed or wounded for every Russian casualty.

While Russia was slowly advancing against dug in Ukrainian forces, the U.S. and NATO provided Ukraine with billions of dollars of military equipment, including the equivalent of several armored divisions (tanks, armored fighting vehicles, artillery, and support vehicles), along with extensive operational training on this equipment at military installations outside Ukraine.

In short, while Russia was busy destroying the Ukrainian military on the battlefield, Ukraine was busy reconstituting that army, replacing destroyed units with fresh forces that were extremely well equipped, well trained, and well led.

The second phase of the conflict saw Russia destroy the old Ukrainian army. In its stead, Russia faced mobilized territorial and national units, supported by reconstituted NATO-trained forces. But the bulk of the NATO trained forces were held in reserve.

The Third Phase – NATO vs. Russia

These are the forces that have been committed to the current fighting. Russia finds itself in a full-fledged proxy war with NATO, facing a NATO-style military force that is being logistically sustained by NATO, trained by NATO, provided with NATO intelligence, and working in harmony with NATO military planners.

What this means is that the current Ukrainian counteroffensive should not be viewed as an extension of the phase two battle, but rather the initiation of a new third phase which is not a Ukrainian-Russian conflict, but a NATO-Russian conflict.

The Ukrainian battle plan has “Made in Brussels” stamped all over it. The force composition was determined by NATO, as was the timing of the attacks and the direction of the attacks. NATO intelligence carefully located seams in the Russian defenses and identified critical command and control, logistics, and reserve concentration nodes that were targeted by Ukrainian artillery, which operates on a fire control plan created by NATO.

In short, the Ukrainian army that Russia faced in Kherson and around Kharkov was unlike any Ukrainian opponent it had previously faced. Russia was no longer fighting a Ukrainian army equipped by NATO, but rather a NATO army manned by Ukrainians.

Ukraine continues to receive billions of dollars of military assistance, and currently has tens of thousands of troops undergoing extensive training in NATO nations.

There will be a fourth phase, and a fifth phase … as many phases as necessary before Ukraine either exhausts its will to fight and die, NATO exhausts its ability to continue supplying the Ukrainian military, or Russia exhausts its willingness to fight an inconclusive conflict in Ukraine. Back in May I called the decision by the U.S. to provide billions of dollars of military assistance to Ukraine “a game changer.”

Massive Intelligence Failure

What we are witnessing in Ukraine today is how this money has changed the game. The result is more dead Ukrainian and Russian forces, more dead civilians, and more destroyed equipment.

If Russia is to prevail, however, it will need to identify its many failings leading up to the successful Ukrainian offensive and adapt accordingly. First and foremost, the Ukrainian offensive around Kharkov represents one of the most serious intelligence failures by a professional military force since the Israeli failure to predict the Egyptian assault on the Suez Canal that kicked off the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

The Ukrainians had been signaling their intent to conduct an offensive in the Kherson region for many weeks now. It appears that when Ukraine initiated its attacks along the Kherson line, Russia assumed that this was the long-awaited offensive, and rushed reserves and reinforcements to this front.

The Ukrainians were repulsed with heavy losses, but not before Russia had committed its theater reserves. When the Ukrainian army attacked in the Kharkov region a few days later, Russia was taken by surprise.

And then there is the extent to which NATO had integrated itself into every aspect of Ukrainian military operations.

How could this happen? A failure of intelligence of this magnitude suggests deficiencies in both Russia’s ability to collect intelligence data, as well as an inability to produce timely and accurate assessments for the Russian leadership. This will require a top-to-bottom review to be adequately addressed. In short, heads will roll — and soon. This war isn’t stopping anytime soon, and Ukraine continues to prepare for future offensive actions.

Why Russia Will Still Win

In the end, I still believe the end game remains the same — Russia will win. But the cost for extending this war has become much higher for all parties involved.

The successful Ukrainian counteroffensive needs to be put into a proper perspective. The casualties Ukraine suffered, and is still suffering, to achieve this victory are unsustainable. Ukraine has exhausted its strategic reserves, and they will have to be reconstituted if Ukraine were to have any aspirations of continuing an advance along these lines. This will take months.

Russia, meanwhile, has lost nothing more than some indefensible space. Russian casualties were minimal, and equipment losses readily replaced.

Russia has actually strengthened its military posture by creating strong defensive lines in the north capable of withstanding any Ukrainian attack, while increasing combat power available to complete the task of liberating the remainder of the Donetsk People’s Republic under Ukrainian control.

Russia has far more strategic depth than Ukraine. Russia is beginning to strike critical infrastructure targets, such as power stations, that will not only cripple the Ukrainian economy, but also their ability to move large amounts of troops rapidly via train.

Russia will learn from the lessons the Kharkov defeat taught them and continue its stated mission objectives.

The bottom line – the Kharkov offensive was as good as it will get for Ukraine, while Russia hasn’t come close to hitting rock bottom. Changes need to be made by Russia to fix the problems identified through the Kharkov defeat. Winning a battle is one thing; winning a war another.

For Ukraine, the huge losses suffered by their own forces, combined with the limited damage inflicted on Russia means the Kharkov offensive is, at best, a Pyrrhic victory, one that does not change the fundamental reality that Russia is winning, and will win, the conflict in Ukraine.

Scott Ritter is a former U.S. Marine Corps intelligence officer who served in the former Soviet Union implementing arms control treaties, in the Persian Gulf during Operation Desert Storm and in Iraq overseeing the disarmament of WMD. His most recent book is Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika, published by Clarity Press.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.