Far-right leader Giorgia Meloni has claimed victory in Italy’s election, and is on course to become the country’s first female prime minister.

Ms Meloni is widely expected to form Italy’s most right-wing government since World War Two.

That will alarm much of Europe as Italy is the EU’s third-biggest economy.

However, speaking after the vote, Ms Meloni said her Brothers of Italy party would “govern for everyone” and would not betray people’s trust.

“Italians have sent a clear message in favour of a right-wing government led by Brothers of Italy,” she told reporters in Rome, holding up a sign saying “Thank you Italy”.

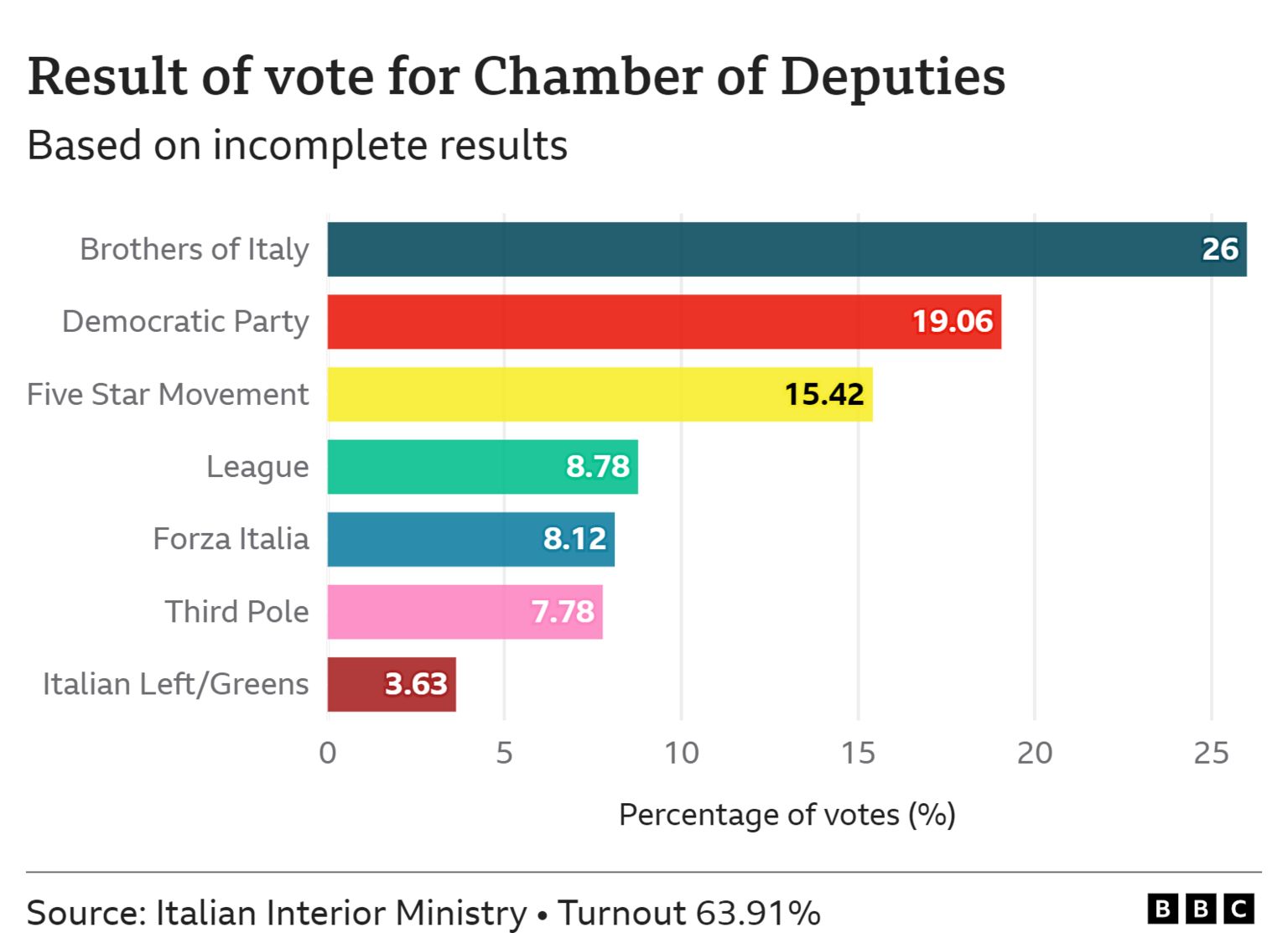

She is set to win around 26% of the vote, ahead of her closest rival Enrico Letta from the centre left. Mr Letta told reporters on Monday that the far-right victory was a “sad day for Italy and Europe” but his party would provide a “strong and intransigent opposition”.

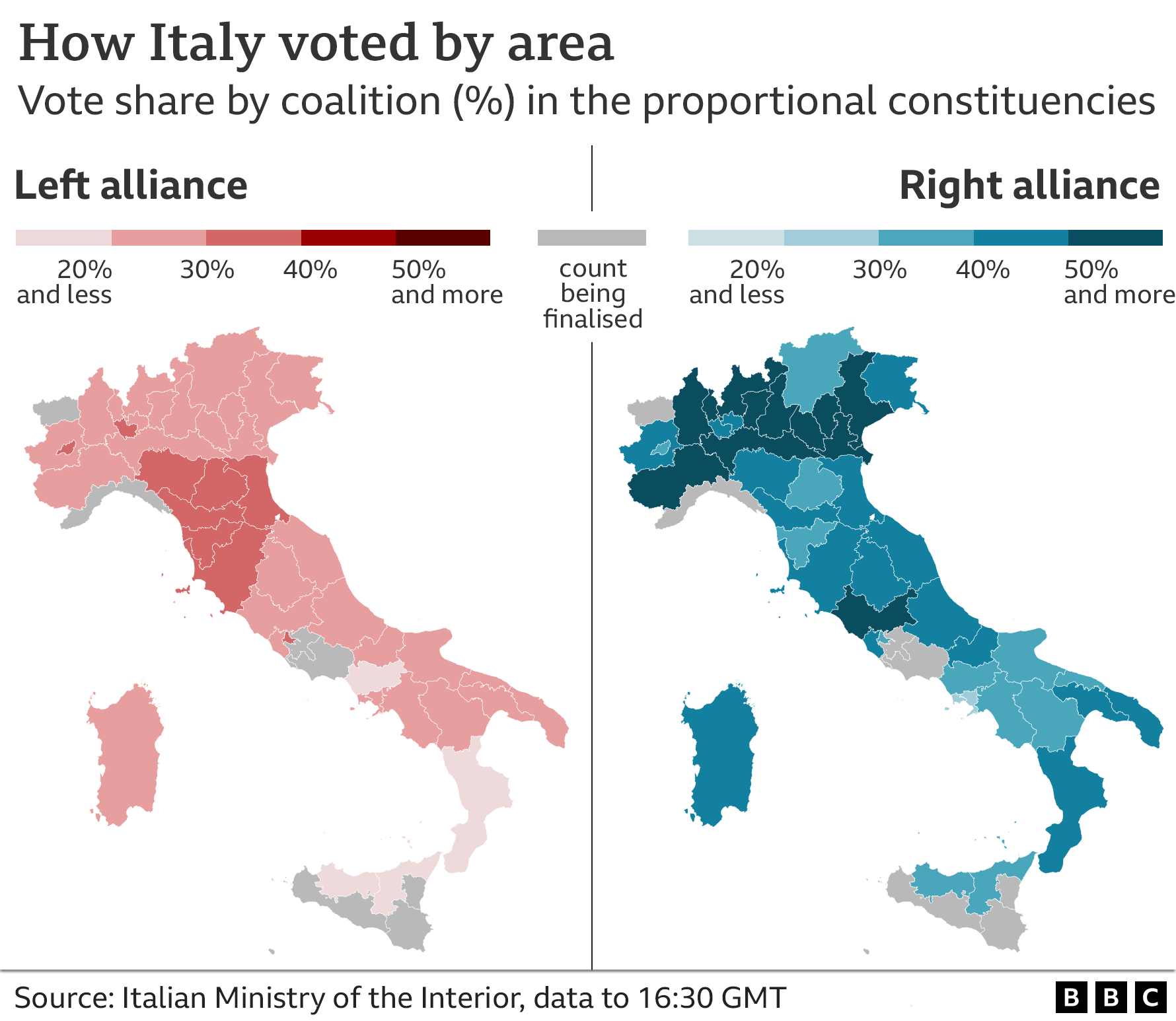

Ms Meloni’s right-wing alliance – which also includes Matteo Salvini’s far-right League and former PM Silvio Berlusconi’s centre-right Forza Italia – will take control of both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, with around 44% of the vote.

Four years ago, Brothers of Italy won little more than 4% of the vote but this time benefited from staying out of the national unity government that collapsed in July.

The party’s dramatic success in the vote disguised the fact that her allies performed poorly, with the League slipping below 9%, and Forza Italia even lower.

Their big advantage, however, was that where they were able to put up one unified candidate in a constituency, their opponents in the left and centre could not agree a common position and stood separately.

Giorgia Meloni appears certain to become prime minister but it will be for the president, Sergio Mattarella, to nominate her and that is unlikely to happen before late October.

Although she has worked hard to soften her image, emphasising her support for Ukraine and diluting anti-EU rhetoric, she leads a party rooted in a post-war movement that rose out of dictator Benito Mussolini’s fascists.

Earlier this year she outlined her priorities in a raucous speech to Spain’s far-right Vox party: “Yes to the natural family, no to the LGBT lobby, yes to sexual identity, no to gender ideology… no to Islamist violence, yes to secure borders, no to mass migration… no to big international finance… no to the bureaucrats of Brussels!”

The centre-left alliance was a long way behind the right with 26% of the vote and Democratic Party figure Debora Serracchiani argued that the right “has the majority in parliament, but not in the country”.

In truth the left failed to form a viable challenge with other parties after Italy’s 18-month unity government fell apart, and officials were downbeat even before the vote. The Five Star Movement under Giuseppe Conte won a convincing third place – but did not see eye to eye with Enrico Letta even though they have several policies in common on immigration and raising the minimum wage.

Turnout fell to a record low of 63.91% – nine points down on 2018. Voting levels were especially poor in southern regions including Sicily.

Italy is a founding father of the European Union and a member of Nato, and Ms Meloni’s rhetoric on the EU places her close to Hungary’s nationalist leader Viktor Orban.

Her allies have both had close ties with Russia. Mr Berlusconi, 85, claimed last week that Vladimir Putin was pushed into invading Ukraine while Mr Salvini has called into question Western sanctions on Moscow.

Ms Meloni wants to revisit Italian reforms agreed with the EU in return for almost €200bn (£178bn) in post-Covid recovery grants and loans, arguing that the energy crisis has changed the situation.

Italy is already the second most indebted country in the eurozone and Prof Leila Simona Talani of King’s College London believes the next government will face a clutch of serious issues.

“They have no experience economically. Tax cuts will be a problem, so Italy will have less revenue and it’s heading for a recession, so it’ll face problems with the financial markets and with Europe. How will they find the money to tackle the rising energy prices?”

The Hungarian prime minister’s long-serving political director, Balazs Orban, was quick to congratulate Italy’s right-wing parties: “We need more than ever friends who share a common vision and approach to Europe’s challenges.”

In France, Jordan Bardella of the far-right National Rally said Italian voters had given European Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen a lesson in humility. She had earlier said Europe had “the tools” to respond if Italy went in a “difficult direction”.

However, Prof Gianluca Passarrelli of Rome’s Sapienza University told the BBC he thought she would avoid rocking the boat on Europe and focus on other policies: “I think we will see more restrictions on civil rights and policies on LGBT and immigrants.”

Ms Meloni wants a naval blockade to stop migrant boats leaving Libya, and Matteo Salvini is known to covet the job of interior minister which he held three years ago. However, he is currently on trial for barring a boat from docking as part of his policy to close ports to rescue boats.

This election marks a one-third reduction in the size of the two houses, and that appears to have benefited the winning parties.

The make-up of the Chamber and Senate is not yet clear but a YouTrend projection said the right-wing alliance would hold as many as 238 of the 400 seats in the lower house and 112 of the 200 seats in the upper house.

As for the centre left, they are projected to have 78 seats in the Chamber and 40 in the Senate.