Historian Rashid Khalidi’s concise and at times personal take on a century of colonial conquest and resistance in Palestine is a highly accessible read that focuses on key events and themes.

There is a plethora of books on the Arab-Israeli conflict and yet those of us who teach the subject on college campuses are desperately looking for new ones to use as textbooks on the Palestinian question. Rashid Khalidi’s new book, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonial Conquest and Resistance, 1917-2017, takes a fresh new approach.

Even among the good informative books on the conflict, like Sami Hadawi’s Bitter Harvest or Charles D. Smith’s Palestine and the Arab Israeli conflict, the tendency is to produce an overly detailed, blow-by-blow account of wars to introduce students to the origins and evolution of the conflict.

In his book, Khalidi refreshingly avoids presenting a tedious descriptive chronology and opts for a highly selective account of the conflict, dividing the book into themes and events.

He also adds personal details, regarding himself or his family, or even other members of the extended Khalidi family, giving the book a more interesting and accessible take. The historian was my advisor at the American University of Beirut at undergraduate and graduate levels.

He wrote his own PhD dissertation under Albert Hourani, entitled British Policy Toward Syria and Palestine and knows the history inside out. He also participated in Middle East negotiations as an advisor to the Palestinian delegation in Madrid and later in Washington D.C. Not surprisingly, Khalidi has written prolifically about Palestine, including a book on the formation of Palestinian identity.

Damning Account of Balfour Declaration

By avoiding the production of a chronology, his book focuses on key events and personalities. His account of the Balfour Declaration is concise but damning about the cunning British policy, a theme he had dealt with in his PhD dissertation.

He also includes correspondence at the very end of the 19th century between prominent Ottoman politician Diya’ Al-Khalidi and Austro-Hungarian political activist Theodore Herzl, considered the father of modern Zionism. The correspondence puts to rest the notion that Herzl, or early Zionists in Europe, simply did not know that Palestine was already inhabited or that the Palestinians did not fear very early on a grave danger from the Zionist project, which intended to steal their land, and subsequently their entire, ancestorial homeland.

Khalidi cites the words of Herzl himself, who wrote in his diary:

“We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries…Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.”

Colonial Myths Dispelled

Herzl is still treated in the West as a humanist dreamer. He surely dreamt of the forceful wholesale expulsion of the native population. It is a racist mindset that led people like Herzl to assume Palestinians were too backward politically to manifest national attachment to their homeland and to fight for its retention.

The notion that ethnic cleansing of the natives happened as an accident is belied by the evidence contained in the early writings of Herzl. The entire Zionist project was predicated on the principle of creating a new Jewish homeland over the ruins of an existing Palestinian homeland, where the majority of the population was not Jewish and where Jews and non-Jews had lived side-by-side for centuries. It is Zionism that poisoned this relationship.

Khalidi does not fill the book with numerous facts and events, but selects the most important to give the reader a good view of the overall picture. He, for example, informs us that in the Arab Revolt of 1936-39, 10 percent of the adult Arab population was “killed, wounded, imprisoned or exiled”. This in itself shows how the British acted as the midwife for the crime of erasing the Palestinian homeland to make room for a new homeland intended solely for Jewish immigrants from Europe. Local Jews were initially opposed to Zionism.

Khalidi also dispels the myth that Palestinian and Arab societies were in a state of stagnation. He points out that “thirty-two new newspapers and periodicals were established in Palestine between 1908 and 1914, with even more in the 1920s and 1930.” He builds on his previous work on Palestinian identity to show Palestinians forged a national identity not different from modern national identities of other groups.

Responding to the Zionist notion that Palestinian nationalism only emerged in response to Zionism, Khalidi points out that Zionism itself was shaped in response to antisemitic hatred in Europe.

British Trickery and Deception

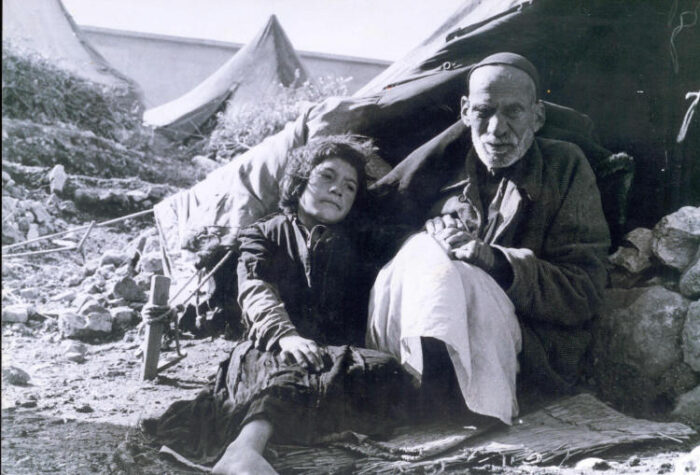

Lord Peel and Sir Horace Rumbold, chairman and vice chairman of the Palestine Royal Commission, leaving their offices in Jerusalem during the Arab Revolt in 1936. (Creative Commons/Public Domain)

The author is at his best documenting British deception and trickery. He refers to a dinner at Lord Balfour’s home where British Prime Minister Lloyd George, Balfour and Conservative Winston Churchill met and they assured

“Weizman that by the term ‘Jewish national home’ [in the Balfour Declaration] they ‘always meant an eventual Jewish state’. Lloyd George convinced the Zionist leader that for this reason Britain would never allow representative government in Palestine. Nor did it.”

This only validates early Arab rejection of British promises and pledges. Palestinians were aware, as this book shows, that before the advent of the British mandate, Britain was committed to the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine. The book chronicles the British repression of the Arab Revolt in 1936-39. One 81-year-old rebel leader “was put to death in 1937.”

“Under the martial law in force at the time, that single bullet was sufficient to merit capital punishment…Well over a hundred such sentences of executions were handed down after summary trials by military tribunals, with many more Palestinians executed on the spot by British troops.”

However, I disagree with Khalidi’s contention that the Palestinians were at fault for rejecting the 1939 White Paper. The Palestinians were actually correct in doubting British intentions. The phrasing of the paper did not at all promise the establishment of an independent Palestinian Arab state, especially given Britain’s commitment to the establishment of a Jewish state superseded any gesture it was willing to make towards the Arabs.

Furthermore, while the paper pledged to temporarily limit Jewish immigration, the influx of illegal Jewish immigration continued unabated.

On the founding of the Arab League in 1945 at the behest of the British government, he describes the bitter disappointment of Dr. Husayn Khalidi, the author’s uncle, when the “six Arab states [which] formed the Arab League… decided to remove reverences to Palestine from the League’s inaugural communique” and they insisted on selecting the Palestinian representative, who was a loyal servant of British wishes.

In selecting Israeli war crimes to include in his narrative, Khalidi effectively includes massacres largely unknown by Western readers. When Israel invaded the refugee camps of Khan Yunis and Rafah in November 1956, “more than 450 people, male civilians, were killed, most of them summarily executed.” Arabs know the history of Israel as a chronology of massacres and war crimes.

Khalidi is at his best in covering the PLO’s experience in Lebanon and the brutality of Israeli aggression against Lebanese and Palestinians. He lived through the siege of Beirut in 1982 and he wrote a classic book on the PLO’s political and military performance during the siege. He provides the reader with a first-person account of life under the indiscriminate bombardment of West Beirut.

Points of Disagreement

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, U.S. President Bill Clinton and the PLO’s Yasser Arafat at Oslo Accords signing ceremony, September 13, 1993. (Wikimedia Commons/IDF)

I disagree with Khalidi on two major points in this book. He repeatedly faults the Palestinian leadership of Arafat for not focusing its attention on the American scene. But Khalidi concedes, in this book and in other works, that the U.S. was fundamentally hostile to Palestinian interests and frequently lied to and deceived Arab interlocuters.

He says explicitly “the United States could never be an honest broker given the commitments it had undertaken” to Israel. And why should this liberation movement address itself to the single most influential country in the construction of the Israeli nuclear fortress?

Furthermore, Khalidi knows U.S. foreign policy decision-making was nothing like its domestic policy-making where — in theory at least — various interest groups get a seat at the table and compete. In foreign policy there is a powerful Israel lobby that has been able to monopolize, with the consent of both parties, the making of U.S. Middle East policy.

The Arabist faction at the U.S. Department of State had been decimated by the Clinton administration and the pro-Israeli Washington Institute for Near East Policy became the center of Middle East thinking and propositions in the nation’s capital. The public, even if swayed by some Arab lobbying, would not be able to affect policy. In France and U.K., sympathy for the Palestinians has not been translated into the policies of the leadership of ruling parties.

Secondly, it is rather surprising that a book on resistance to Israel would not address the earth-shaking achievements of the Lebanese resistance movement, which was able in the July 2006 war prevent Israel from advancing one inch into Lebanon in 33 days of war. In 1967, three Arab armies were defeated in a matter of hours, while a Lebanese band of volunteers humiliatingly expelled Israeli army from South Lebanon and deterred it from contemplating another occupation.

That model of resistance undermines the thesis of Khalidi that armed resistance has proven its futility and that the non-violent intifada of 1987 was a successful alternative model to armed resistance.

PLO Military Operations Ineffective

Yasser Arafat, chairman of the Executive Committee of the Palestine Liberation Organization, at a U.N. press conference, May 2, 1996. (UN Photo/Evan Schneider)

But that intifada did not succeed in making any gains for the Palestinians. On the contrary, the model of non-violent resistance was then used by Western powers to deprive the Palestinians of the basic right of military resistance to a brutal occupation. The current alliance between Lebanese resistance and the resistance in Gaza shows that the PLO could have done a great deal to husband its resources and to provide a regional network for the coordination of resistance activities.

Instead, PLO’s military operations largely amounted to an abysmal failure and the leadership was never serious about forming an effective military resistance movement. Arafat used symbolic military operations to extract diplomatic attention from the West. But even that calculus failed, as evidenced by the meager offerings of Oslo peace accords signed in 1993 and 1995.

The author reflects on his experience as an advisor to the Palestinian negotiating team. He says:

“Had I understood how heavily the deck was stacked and that the United States was bound in this way by a formal commitment—which meant that Israel effectively determined both its own position and that of its sponsor—I probably would not have gone to Madrid or spent much of the next two years engaged in Washington talks.”

This book can serve as an essential primer on the Palestinian question and fills a gap in the library of books on Palestine. The combination of personal narrative and academic investigation of the origins and evolution of the conflict provides students with solid background of the topic, without burdening them with details and minutia.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004) and ran the popular The Angry Arab blog. He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.