From its founding origins as a secular republic to army coups, footballing success and the rise of Erdoğan, we look at 100 years of Turkey since 1923

Formed in 1923, Turkey marked its centenary on Sunday with nationwide celebrations. The republic was founded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, a general turned politician, who rescued his country from the clutches of European rule after the first world war and restructured the remainder of what was once a transcontinental and multicultural Islamic empire into a lean new Anatolian republic, intending it to resemble Europe more closely.

“The Turkish nation has fallen far behind the west,” Atatürk told a German officer during the first world war. “The main aim should be to lead it to modern civilisation.” To that end, he began implementing political, social and cultural reforms that would change his country for ever, creating new social and political cleavages as Turkish citizens began contesting the meanings of their country’s history, symbols and identity.

Forging a nation while attempting a clean break with its past can be fraught enterprise in the most favourable circumstances, but following independence Turkey’s new leaders had a daunting task. Turkey was war-weary, battered by almost continuous fighting with various European empires from the 19th century into the 20th and with a large population of Muslim refugees who fled from territories it lost control of in those wars.

As the country turns 100, Turkey’s republican era is a story of its leaders working to continually redefine the country as they tend to the scars of its history, while attempting to find their nation’s place in the world.

November 1922

Atatürk abolished the sultanate, driving the Ottoman royal family into exile. Sixteen days later, Mehmed VI, the last sultan, was photographed boarding a British warship as he fled to Malta, marking the end of a dynasty that had ruled Anatolia, the Balkans and large parts of the Middle East and north Africa for hundreds of years.

29 October 1923

Atatürk gathered representatives at the Turkish Grand National Assembly, where he declared Turkey a republic. Atatürk envisioned Turkey as a secular republic and a home for the Muslim populations of post-Ottoman territories. In March 1924, he abolished the caliphate, an office that gave the sultan added religious legitimacy, leaving a vacuum in its place across the Muslim world.

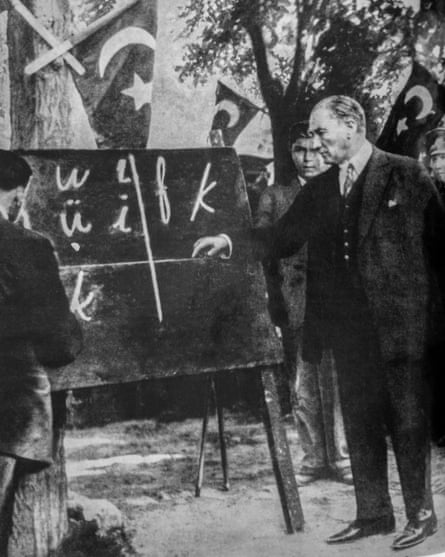

1 November 1928

A new Turkish alphabet law was passed, making the use of Latin letters compulsory in all public communications and the education system and discarding the use of the Arabic script for the Turkish language. The move erected a firewall around Turkey’s past as the country continued its effort to redefine itself.

10 November 1938

Atatürk died, leaving a towering legacy as a commander who rescued Anatolia from European occupation after the first world war and founded a new nation in the embers of the Ottoman empire. His close confidant, İsmet İnönü, took over before Turkey held its first free election. İnönü then voluntarily gave up power.

15 May 1950

Adnan Menderes was elected prime minister of Turkey in the country’s first democratic election, ushering in a new era in which the country would enter the US camp during the cold war and become a member of Nato in 1952. The military ousted his government on 27 May 1960, accusing him of undermining secularism. He was sentenced to death, then hanged on 2 January 1961. It was the first of four military takeovers in Turkish history.

26 January 1974

Bülent Ecevit was elected prime minister on a centre-left platform with 33.5% of the vote, leading the Republican People’s party back to power. A former journalist and talented poet, Ecevit’s career in politics lasted more than four decades. A four-time prime minister, Ecevit earned his country EU candidate status and was in power when Abdullah Öcalan, the leader the Kurdish militant group the PKK, was captured. He is perhaps better remembered for his decision in 1974 to send Turkish troops into Cyprus.

When asked in May 2000 what he thought his greatest achievement was, he cited a major reform to workers’ rights that he passed as labour minister in 1963. Speaking to the Sabah newspaper, he said: “For me, it is more important than all of them to grant the workers the right to establish trade unions, because I am a leftist.” He died aged 81 in 2006.

20 July 1974

Turkish troops pushed into Cyprus in 1974 in response to an attempt by a military government in Athens to annex the island to Greece. Turkey established the self-styled Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in the island’s northern regions for the Turkish Cypriot population. The state is recognised only by Ankara.

1 October 1976

Muhammad Ali visited Istanbul in October 1976 and prayed alongside the deputy prime minister, Necmettin Erbakan, at Sultan Ahmet mosque. The world heavyweight champion’s visit had an electrifying impact on the Turkish public. During his trip, Ali said he was retiring from boxing to “devote all my energy to the propagation of the Muslim faith”, though he would continue in the ring for many years.

20 May 1977

The Orient Express departed Gare de Lyon on its last trip to Istanbul. The 1,900-mile, 56-hour train journey connected Paris with Istanbul, calling at cities such as Venice, Belgrade and Sofia.

7 September 1980

A communique released by Turkey’s armed forces at 04.30am announced that the army, led by Kenan Evren, had dissolved the government of Süleyman Demirel. The army overhauled the country’s political class, leaving some of the scions of Turkish politics such as Alparslan Türkeş, Ecevit and Erbakan in the cold for much of the next decade. Evren would rule Turkey for seven years, but yielded power back to civilians after drawing up a new constitution in 1982.

13 December 1983

Turgut Özal became prime minister after his Motherland party came out on top in Turkey’s first election since the shutdown of political activity. Özal often spoke about his Kurdish ancestry and was openly religious, a first for a Turkish politician of his seniority. He combined an expansion of religious freedoms with economic liberalisation, which empowered large parts of Turkey’s conservative religious population, who had previously been excluded from public life. A former World Bank economist, he ruled Turkey for six years as prime minister, then became president from 1989 until his death in 1993. During this period, Turkey shifted politically and economically to the right.

25 June 1993

Turkey elected Tansu Çiller, a former economics professor and politician, as the country’s first female prime minister. Addressing supporters after her victory in Ankara, Çiller declared: “We have changed Turkish history.”

11 August 1999

In the summer of 1999, a 7.6-magnitude earthquake hit, striking the Kocaeli province near Istanbul. The quake devastated the region, levelling thousands of homes and resulting in the deaths of more than 17,000 people.

17 May 2000

Turkish side Galatasaray beat Arsenal 4–1 on penalties in the Uefa cup final, becoming the first Turkish football team to achieve success on the European stage.

22 June 2002

Turkey’s footballing success continued when the national team reached the semi-final of the 2002 World Cup held in Korea and Japan, beating Senegal 1–0. Kevin Mitchell was in Osaka for the Guardian that day. “If they reproduce something similar in Saitama on Wednesday,” he wrote, “they might continue the run of shocks that has characterised a most unusual and enthralling World Cup.” The victory put them up against the eventual winners, Brazil. The Turkish team finished third overall.

15 March 2003

The Justice and Development party (AKP) won the general election poll by a landslide, giving Recep Tayyip Erdoğan his first shot at national power. Abdullah Gül, who led the AKP to the victory, lifted a ban on Erdoğan seeking the top office, then stepped aside. “Poverty will be overcome. You can have a secular government; it doesn’t conflict with Islam. Islam is a religion,” Erdoğan said, addressing concerns about the religious roots of his party.

The elections were held after an economic crisis that was still fresh in the public memory. The AKP promised better economic governance, an expansion of freedoms, and a European future for Turkey. Erdoğan would go on to become one of the most consequential, polarising and longest-serving figures in Turkish political history.

28 May 2013

After a period of breakneck reforms that were lauded domestically and internationally, Erdoğan faced the first major test of his rule when millions of people across the country took to the streets in protests that lasted three weeks. Demonstrators gathered in the central Istanbul district of Beyoğlu to halt a plan to turn Gezi park into a shopping centre, which snowballed into larger expressions of discontent against the AKP. They were met with force by police and eight people died, four as a result of police violence, and 8,000 were injured.

September 2015

The corpse of a three-year-old refugee, Alan Kurdi, washed up on the shores of a beach in Bodrum after the boat he was in capsized, triggering a global outcry about the plight of people fleeing the war in Syria. Turkey took in more than four millon refugees from Syria.

15 July 2016

A faction within the Turkish military attempted to overthrow the government. Erdoğan called on the public to take the streets through an iPhone call broadcast on CNN Türk. People across Turkey did so. The Turkish government blamed the coup on the US-based Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen and his followers. Thousands of people suspected of being members of the organisation were arrested in the aftermath.

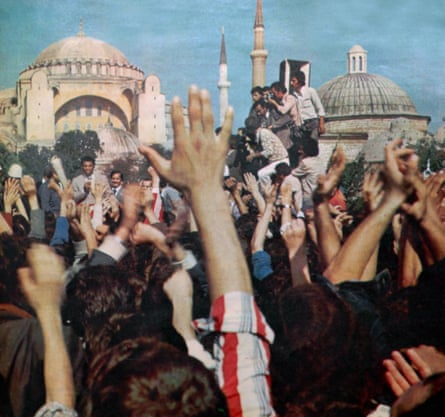

24 July 2020

Hagia Sophia was reopened to Muslim worshippers, 86 years after Atatürk converted it from a mosque to a museum in a symbolic decision to underline Turkey’s secular new regime. The structure, a Unesco world heritage site, was an orthodox Christian cathedral in the Byzantine era before Ottoman forces conquered the city, turning it into a mosque in the 15th century. Erdoğan attended the first Friday prayer, which coincided with the official opening ceremony.

28 May 2023

After a hotly contested election, opposition challenger Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu fell short and Erdoğan was re-elected to a revamped presidency where its once ceremonial nature was transformed into a more politically charged role. Erdoğan was granted a mandate for five more years, taking him to the two-term legal limit.

Erdoğan’s legacy is bitterly contested. Supporters credit him with lifting restrictions on Islam, modernising the country’s infrastructure, and raising its global profile. His critics accuse him of harming the country’s economy, polarising Turkish politics, and presiding over a period of tightened restrictions on political freedoms.

… there is a good reason why