aniel Yalke was twenty when he left Ethiopia and set off for Europe. One of six siblings from a poor family in Cherkos, a tough neighborhood in Addis Ababa, he had recently graduated from a technical college, where he’d trained to be an electrician. Some of his friends from Cherkos had paid smugglers to reach Europe. These friends now sent Yalke boastful texts about their better lives in Italy, France, and England. Yalke, a handsome youth with a wide smile, didn’t see much of a future for himself in Addis Ababa. It was difficult to make money as an electrician in the city, and the work was dangerous: a friend from school had been fatally electrocuted.

In the summer of 2017, Yalke and his best friend from Cherkos, Israel Endale, phoned a broker they knew only as Binyam, who had grown up in their neighborhood. Binyam, who lived in Khartoum, in Sudan, said that he could arrange for their journey to Europe. Starting from Sudan, they’d cross the Sahara, pass through the war-ravaged state of Libya, and then head for Italy on a boat. People often refer to this path as the Central Mediterranean Route.

Yalke and Endale told their families of their plan only a day before they were scheduled to leave. Both families desperately tried to dissuade them, reminding them of people who’d died or been imprisoned on the route, and promising to help them find better opportunities in Addis Ababa. Yalke was initially persuaded by his family, and said that he would reconsider the idea. But Endale was resolute, and within a few hours he’d turned Yalke back to the original plan. The next morning, they secretly boarded a bus. They took no mementos with them, just a few items of clothing, some cash, and a phone. Yalke felt safe with Endale—they were so close that they’d eaten dinner together every night for years, switching between one family’s house and the other’s.

The bus trip to Sudan took four days and cost them about eighty dollars each. Yalke knew that the remaining journey would be arduous, but as a business transaction it seemed simple. Yet, after he and Endale arrived in Khartoum, Binyam told them, by phone, that he couldn’t meet them right away. He directed them to wait at a safe house in Al-Diyum, a neighborhood frequented by migrants from the Horn of Africa. The men guarding the safe house had never heard of Binyam, and they became aggressive with Yalke and Endale, even threatening to shoot them.

After several tense hours, Binyam arrived with another broker, Birhane, whom he described as his superior. The guards knew Birhane and calmed down. Birhane said that Yalke and his friend each could reach Europe for ninety thousand birr, the equivalent of nearly four thousand dollars. The price seemed like a bargain—Yalke knew people who had made the journey and had paid much more. The terms also seemed fair: Birhane said that Yalke and Endale could wait to pay the full amount until they were about to board a boat for Italy.

As is customary for migrants, neither he nor Endale was carrying a large amount of cash. Yalke had hidden money at a neighbor’s house in Addis Ababa, and planned to ask his family to relay payments to the smugglers on his behalf. In Khartoum, Yalke called his family and told them about his decision to migrate, and about the cost. His family begged him to return to Addis Ababa. He said that he was determined to make the journey and wasn’t afraid.

A few days later, Yalke and Endale joined around sixty other Ethiopians and Eritreans in the bed of a dump truck. Some Sudanese men drove the migrants north, into the Sahara. It was searingly hot in the truck, but Birhane had given Yalke and Endale cookies and fruit juice. After three days, they arrived at the border of Chad. A group of Libyans put the migrants in Land Cruisers and continued through the desert. The Libyans smoked marijuana constantly, and they were cruel. They offered no food, and although they gave the migrants water, they laced it with petroleum so that they didn’t drink too much. At one point on the journey, Yalke witnessed some of the Libyans dragging an Eritrean woman away and raping her. He wanted to intercede but was too afraid to do so. As he recently told me, the smugglers were “very heavily armed, and also crazy—they need very little reason to do heinous things.

In southeastern Libya, the migrants arrived at a camp in Kufra—a hub for the smuggling of people, drugs, and weapons. They were still many hundreds of miles south of the Mediterranean. Yalke and Endale expected it to be a short stop. But, after a week, the Libyan guards at the camp said that they wouldn’t release them until Yalke and Endale handed over all the birr that they’d agreed to pay Birhane upon arriving at the coast. Yalke and Endale didn’t know it yet, but Birhane had staked them while gambling, and lost; they now belonged to another smuggler.

Yalke and Endale remained stuck in Kufra for months. The desert nights were frigid, and Endale, whose lungs had always been fragile, began having serious trouble breathing. After many arguments and beatings, each migrant agreed to pay the ninety thousand birr. Their families, whom Yalke and Endale were allowed to contact by phone, arranged the transfer of the money from Ethiopia. They and other captives who paid what was demanded were told that they would soon be headed toward the Mediterranean. Yalke, who had done menial jobs around the camp to curry favor with the guards, persuaded them to release Endale first, on account of his poor health. Yalke followed three weeks later.

To cross the Libyan desert, Yalke and at least fifty others were told, they needed to hide in a crawl space underneath an industrial load of cement in a huge freight truck. They travelled for twelve hours in this cramped fashion. The next day, the group was transferred to a space in a tanker truck that was half loaded with oil. The heat and the smell were intolerable. isis fighters patrolled the area. “It was scary,” Yalke recalls. “If isis found us, God knows what they would have done.”

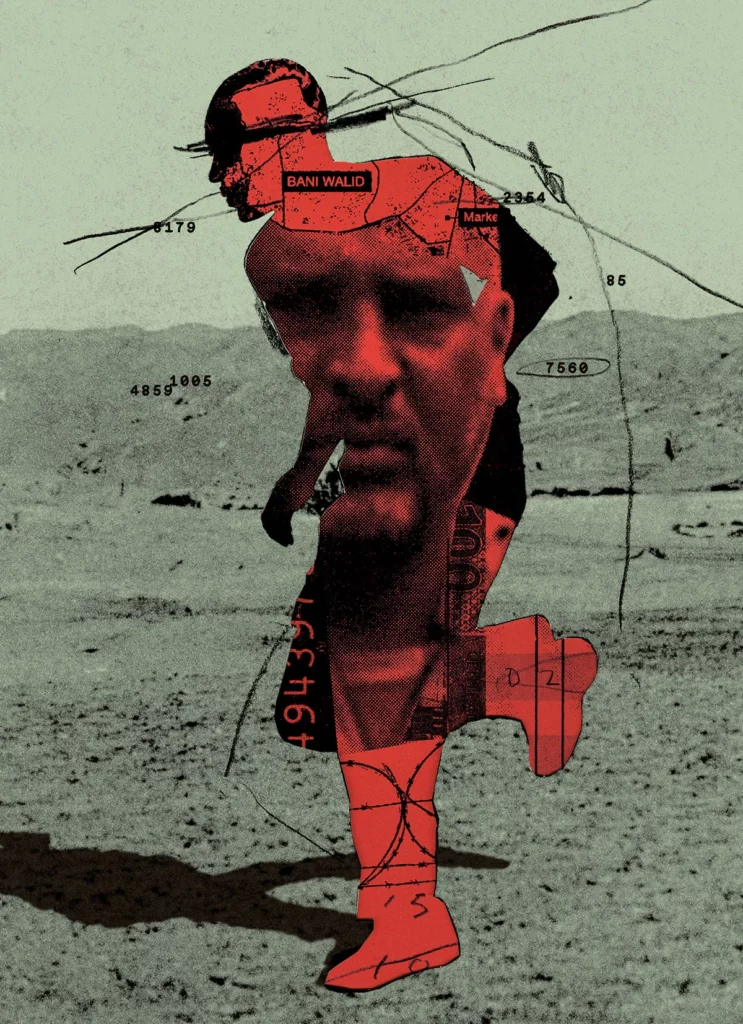

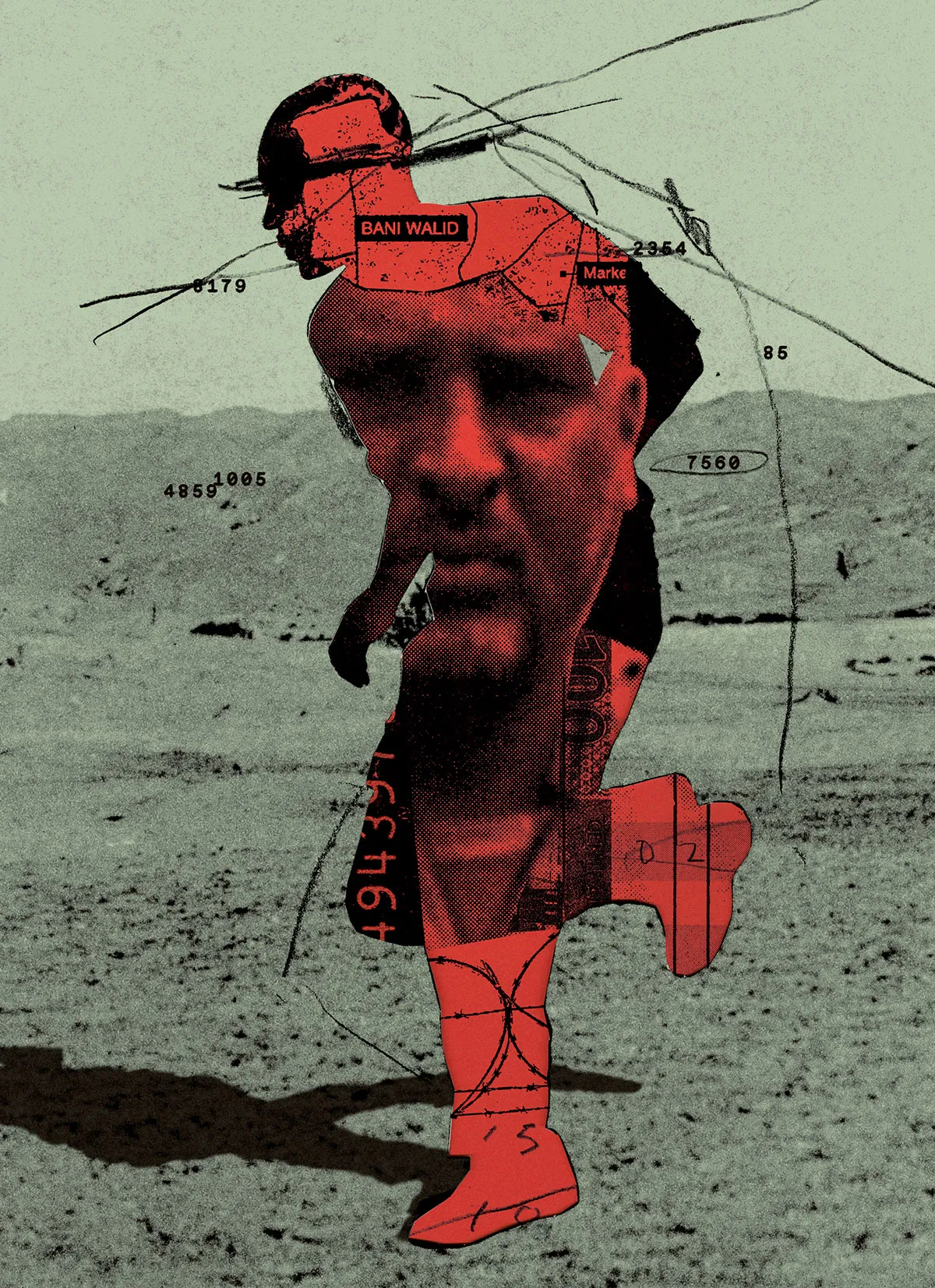

Finally, they arrived in Bani Walid, an oasis town ninety miles southeast of Tripoli. The truck entered a walled compound, and the migrants were herded into a dilapidated warehouse. At first, Yalke felt relief: they had arrived somewhere it might be possible to eat and rest. But he soon realized that he was in an even worse situation. Some two thousand migrants were crammed inside the compound.

Yalke initially couldn’t tell who was in charge. Then he determined that the boss of this camp was a middle-aged man with a hulking frame and hooded eyes. He carried a pistol in his waistband and was flanked by half a dozen guards armed with rifles. One day, the boss told Yalke and the other newcomers that any deal they had struck before arriving in Bani Walid was invalid. To cross the Mediterranean, they needed to pay him fifty-five hundred dollars. The boss declared that he would give them a month to procure the funds; if they failed, they would be tortured on a regular basis until they delivered the money or died.

The boss warned his captives, “It’s going to cost me about ten dinars”—seven dollars—“to kill you.” This was the price of a muslin sheet that the guards used to wrap corpses before burying them in the desert.

The boss was one of the most notorious human traffickers in Africa. He was known universally by his first name: Kidane.

Like many thousands of his victims, Kidane Zekarias Habtemariam is from Eritrea, a small nation in the Horn of Africa. Since gaining independence from Ethiopia, in 1993, Eritrea has been a heavily militarized one-party state ruled by President Isaias Afwerki. There is no free press. National service is mandatory, capriciously assigned, and indefinite in duration. Religious minorities are persecuted. Long prison terms or capital sentences for minor offenses, including insulting the government, are common. Travel is severely limited, and people of conscription age are rarely permitted to leave the country. In Freedom House’s annual assessment of political rights and civil liberties, Eritrea scores the same as North Korea.

Unsurprisingly, many Eritreans find their situation unbearable. According to the Pew Research Center, between 2010 and 2017 at least a million people from sub-Saharan Africa migrated to Europe. During this period, the United Nations estimates, the number of Eritreans living in Europe increased by about forty thousand. (The vast majority of them were granted political asylum.) Meron Estefanos, a Swedish Eritrean expert on the diaspora, told me that there were many more Eritrean migrants than official statistics suggest. She believes that, in 2023, as many as eight thousand Eritreans have fled the country every month. Eritrea’s population is supposedly 3.6 million, but she puts it at only 1.5 million.

Starting in the late two-thousands, when migration routes from Africa to Europe became firmly established, many Eritreans joined others from the Horn of Africa on a well-trodden path through Sudan and Libya. At every stage, refugees were forced to make deals with fixers in order to continue their journey. Many of the fixers—and their bosses—were themselves Eritrean. According to multiple sources, high-level Eritrean military officers and politicians allowed smugglers to operate freely along the route, in return for a cut of the profits.

Kidane was one such fixer. He was born into a poor family in Dbarwa, a town fifteen miles south of the Eritrean capital, Asmara, in the nineteen-seventies. (Nobody seems to know Kidane’s exact age, but he is generally thought to be in his early fifties.) Whereas many Eritreans working on the Libyan smuggling routes are illiterate, Kidane finished high school, and is known to be an avid reader. He spent a short period of his military service in Assab, a port on the Red Sea. An Eritrean musician who lives outside the country—but doesn’t wish to be named—knows Kidane well. He told me he believed that Kidane, during his time in Assab, had met a flagrantly corrupt Eritrean general named Tekle (Manjus) Kiflay. In a 2012 U.N. report, Manjus was described as having supervised two types of trafficking operations: one for weapons and one for people. The businesses used the same routes and, often, the same vehicles. According to the U.N. report, the trade in arms generated around $3.6 million a year for Manjus and other Eritrean officers; the trade in people was said to be “much more lucrative.”

If Kidane made such high-level connections as a young man, it took him years to benefit from them financially. According to an Eritrean expatriate now living in Uganda, Kidane worked as a fruit-and-vegetable seller in Asmara during his twenties. He didn’t earn much, and he had a weakness for gambling on cards—in particular, a version of rummy that is popular in Eritrea. (“Always losing,” the expatriate told me.) At some point in the late two-thousands, Kidane went to Sudan. He was penniless, and eager for an opportunity.

In Khartoum, Kidane met people who ran the smuggling routes across the Sahara and toward the Mediterranean. He built up a network of so-called “feeders”: Eritrean expatriates who would bring other migrants to him. Starting around 2010, the migrants would pay a feeder about sixteen hundred dollars to travel from Sudan to the north coast of Africa. The feeder kept a hundred dollars and gave the remainder to Kidane, who then organized the transport across the Sahara. Within a few years, the price for the journey had risen to twenty-five hundred dollars. Out of that sum, Kidane paid a cut to his superiors along the smuggling route; he also covered the cost of transportation, and the bribes that were given to border guards and militiamen.

After the Arab Spring led to revolution in Libya, in 2011, Kidane began working in that country—including in Misrata, a city on the Mediterranean where many migrants ended up before crossing the sea. By 2014, he had garnered enough money and power to work his way up the criminal food chain. He began running a compound at another coastal city, Sabratha, where many migrants were held—and extorted—until sea passage was booked for them. In the desert, Kidane made use of warehouses in Bani Walid owned by a notorious criminal family, the Diabs, who run a trafficking empire in Libya. The Diabs are protected by elements of the Libyan state. The European Union has sanctioned Moussa Diab, the family’s most powerful member, for committing “serious human rights abuses including human trafficking and the kidnapping, raping and killing of migrants and refugees.”

Daniel Yalke fantasized about escaping the Bani Walid camp, but he knew that there was no point in trying. The Diabs had provided Kidane with sixty to seventy armed guards, from Sudan, Chad, and Niger, to enforce discipline and to patrol the perimeter.

Inside the warehouse, there wasn’t enough room for the migrant captives to lie down at the same time, so they took turns sleeping on the concrete floor, some at night and some during the day. There were few opportunities to wash: showers were taken once a month, in groups. Food was dangerously scarce. Once a day, migrants were fed a tiny amount of plain macaroni. Disease was rife.

Yalke noticed that his friend Endale was also a captive in Bani Walid—but for at least two months they were held in different parts of the warehouse, and couldn’t speak. Eventually, they were reunited in a separate warehouse for migrants who had not yet paid Kidane. The place was known as Death Row. Half a dozen people seemed to be dying every night. As Kidane had noted, the guards wrapped corpses in muslin and took them into the desert for burial. When somebody died, a friend or two of the deceased person was allowed to accompany the body and say a prayer before it was interred.

Endale declined markedly after he entered Death Row. His breathing difficulties worsened to the point that he developed a serious lung infection. For about eight months, Yalke tended to his friend, bathing him when he could and giving him as much food as he could spare. They rarely saw sunlight. Then, miraculously, Endale’s mother mustered up the ransom money. Endale was moved to a different warehouse—nicknamed Canada, on account of its benign conditions—where migrants waited to be transported farther north.

A week after Endale went to Canada, Yalke got word that his friend was dead. “I was crushed,” Yalke told me. “He was like my brother.”

Kidane and the guards kept the migrants in a state of perpetual fear. Every few days, people were pulled from the crowd and asked to call a family member on a cell phone. After the migrant explained his plight, he was brutalized while his captors asked the family member for the thousands of dollars it would cost to buy his freedom. A common torture method was searing the prisoners’ flesh with molten plastic. Yalke suffered this punishment. He told me that he still has nightmares. “It’s not just the torture,” he said. “It’s losing friends, begging your family for money, things like that.”

Beatings were generally administered by the guards, but occasionally Kidane himself took over. (Estefanos, the expert on Eritrean migration, told me that the Diabs provided Kidane and other traffickers with experienced torturers.) Yalke told me that his family became so distressed about his beatings that his sister’s husband sold their car to help raise the ransom money. Like several other victims of Kidane whom I met, Yalke showed me dark marks on his body from the molten plastic and from other abuse inflicted on him in Bani Walid. Other victims showed me multiple cigarette burns on their arms.

Kidane preferred that victims’ families send ransom money via hawala, an informal value-transfer system commonly used in the Arab world and in South Asia. Yalke told me that the contact details of Kidane’s trusted recipients in Ethiopia, Sudan, and various European countries were scrawled on a wall of the warehouse, so that migrants could read them out to distraught family members who’d been reached on the phone. Many migrants spent months under Kidane’s control. One Ethiopian man I met, Seleshi Girma, spent more than three years in the compound—his family was desperately poor, and it took them that long to scrabble together the ransom money.

Nearly everybody I spoke to about Kidane believed that he took sadistic pleasure in beatings. Certainly, he inflicted more pain than was necessary to extort his victims, often whipping them with rubber tubing. One female victim, speaking to Le Monde, said that she was repeatedly raped by Kidane during six months of captivity. She called him a “hyena who gets excited at the sight of blood.” Migrants remember soccer games, organized by Kidane, in which players who bungled a chance to score were shot. The winning team was given a female migrant to rape.

Recently, I met Girma in Addis Ababa. He is twenty-eight but looks at least fifteen years older. At a café in the city, he peeled off his T-shirt and showed me a jagged scar from his navel to below his belt line: Kidane and his guards had sliced him open while his family members watched on a video call. In all, Kidane extorted some nine thousand dollars from his family, and Girma never saw a boat. Kidane was a “devil,” Girma said, adding, “Human life means very little to him. He only values money.”

Girma’s story is not unusual: many people who were held captive by Kidane never crossed the sea. Although Estefanos estimates that Kidane did put some fifteen thousand migrants on boats, the financial core of his business seems to have been kidnapping and extortion, not smuggling.

It’s difficult to know exactly how profitable Kidane’s operation was. His business operated freely, because, in part, Libya fell into a state of anarchy after the 2011 revolution. But this political instability also caused difficulties for traffickers. isis fighters in the region frequently took Kidane’s captives hostage themselves. Kidane paid ransoms to get his captives back, then imposed the cost on their families—plus interest. Captives were often traded among traffickers. The result was that many migrants had to pay multiple ransoms before being set free.

Despite the tumult of operating in Libya, money flowed steadily to Kidane. He was becoming a kingpin, but he also remained a parasite: to keep his operation in Bani Walid going, he needed to continue paying off the Diab family. According to Estefanos, Kidane gave around forty per cent of each migrant’s ransom to the Diabs—about two thousand dollars for the typical “fee.” Kidane spent twenty per cent on other costs and kept forty per cent for himself. When Kidane’s racket was at its peak, around 2017, it was generating perhaps as much as ten million dollars a year. An officer at Interpol recently told me that Kidane had amassed “significant wealth” through extortion, but it was difficult to say precisely how big the fortune was—because Kidane had hidden much of it.

Kidane’s victims remember that he often left the compound in Bani Walid for extended periods. In Africa, smuggling is a seasonal enterprise. Most crossings of the Mediterranean occur between April and September, when the water is less rough. During the off-season, Kidane spent much of his time treating himself to decadent fun in the United Arab Emirates, where he set up a clandestine operation to launder the profits from his criminal activities. Several Eritrean associates of Kidane’s, including his brother, Henok, lived for part of the year in Dubai, collecting cash sent from migrants’ families through hawala networks. They then sent this money to Kidane-owned businesses in the Horn of Africa or made investments in the Emirates. According to sources familiar with Kidane’s network, his many purchases included a house in the Emirates for his family (he and his wife have two children); several properties in Asmara; beauty salons in Addis Ababa and Dubai, each of which was given to a different lover; and numerous Toyota Land Cruiser Prados.

Betting is illegal in the U.A.E., but Kidane’s fondness for gambling followed him there. Other Eritreans remember him playing billiards for high stakes in a club inside Eritrea’s modest consulate. (Kidane never had to hide from the Eritrean government or from its foreign diplomats, with whom he apparently maintained a cozy relationship.) He once lost between ten and twenty thousand dollars playing billiards at the club in a single day.

Kidane also arranged high-stakes card games in private rooms in Dubai. An owner of a speakeasy frequented by Ethiopians and Eritreans observed Kidane setting up such games. (The bar owner did not wish to be named, but his closeness to Kidane was vouched for by other Eritreans.) The bar owner said that Kidane’s stake would be kept, in cash, by a driver who waited outside in his car. Kidane drank, but never to excess—when playing cards, he’d nurse a glass of Johnnie Walker Black Label.

In one card game at the Sun & Sands Sea View Hotel, an unprepossessing three-star hotel near the Dubai airport, Kidane lost about a hundred thousand dollars. The speakeasy owner recalled that, whenever Kidane lost at cards, “he never got angry—he just laughed.” One of Kidane’s regular opponents at the card table is said to have used some of the money he made from beating Kidane to build a gaudy hotel in Uganda, on the shores of Lake Victoria.

Though Kidane could be socially awkward—he found it difficult to make a joke, associates say—he was proud of his success, and used his money to cultivate celebrities. He became friends with several prominent Ethiopian and Eritrean performers. Sometimes he paid for someone he admired to travel to Dubai. The speakeasy owner remembered Kidane bragging that he had bought a plane ticket for Daniel Teklehaimanot—an Eritrean cyclist who’d competed in the Olympics—and had paid for him to stay in the hotel at the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building. (Teklehaimanot recalls meeting Kidane in Dubai around 2016, but says that Kidane did not pay for him to be there.)

Several years ago, Kidane is said to have brought Tarekegn Mulu, a traditional Ethiopian singer, to do a set at the Dubai Palm hotel. Kidane paid him thousands of dollars and presented him onstage with a gold necklace. The artists he sponsored often performed songs whose bespoke lyrics celebrated Kidane’s exploits, much in the way that Mexican narcocorridos heroize members of drug cartels. Estefanos knows Eritreans who attended these parties, and she told me that the lyrics to the songs performed in the Dubai Palm “were, like, ‘Kidane, my brother,’ ‘Kidane, the king,’ ‘Kidane, the hero.’ ” Estefanos added, “The more they sing in his honor, the more money they get.”

Despite the many major crimes Kidane committed, he did not attract the focussed attention of law enforcement in Europe for several years. But in the mid-twenty-tens, as migrant crossings of the Mediterranean rose, boats became increasingly overloaded, and many sank. Thousands of people drowned. The E.U. began pouring money into an effort to stop sea crossings at the main point of departure: the Libyan coast. In 2015, the bloc began giving the Libyan Coast Guard millions of euros, with a mandate to stop migrant crossings and arrest the smugglers.

The policy has been an abject failure, in terms of both saving lives and reducing the number of migrants. The Libyan Coast Guard is cruel and easily bought off with bribes; indeed, some Coast Guard officers have sold migrants back to traffickers—or imprisoned, abused, and extorted them in compounds much like Kidane’s. Without such corruption, Kidane’s business could not have flourished; Moussa Diab’s trafficking empire emerged, in no small part, from relationships that he established with Libyans in the government and the military.

The International Criminal Court has yet to bring charges against anyone involved in the trafficking trade in Libya. Meanwhile, Italy—the first destination of many migrant boats—and several other European countries have pursued the bosses of smuggling networks, sometimes with embarrassing results. As Ben Taub reported in this magazine, an Italian investigation led to the imprisonment of an Eritrean who was believed to be a major smuggler; he turned out to be an innocent man with the same name as the criminal.

Kidane may have been of less immediate interest to prosecutors in Europe because his main operation, in Bani Walid, was at one remove from the sea crossings, but his crimes were nevertheless egregious. Many of his victims, after being released from the warehouse, did eventually make it to Europe, and for prosecutors there who cared to listen to the stories of Eritreans and Ethiopians it was possible to construct a vivid and disturbing criminal case against Kidane. The Netherlands has a significant Eritrean community; according to an Eritrean source familiar with Kidane’s network, the Dutch police first began to ask questions about Kidane a decade ago. But officials at Interpol’s unit on human trafficking and migrant smuggling told me that they didn’t begin receiving intelligence reports about Kidane until October, 2019. By that time, he had been operating on the migrant trail for years.

In February, 2020, a twenty-one-year-old Ethiopian man named Fuad Bedru was talking with a friend on a street in Addis Ababa when a passerby caused him to do a double take. It was Kidane. Bedru had spent much of the previous three years trying unsuccessfully to reach Europe—and for several months he’d been held captive in Bani Walid. The first night that Bedru spent at the camp, he was identified as a troublemaker because he had escaped from another abusive trafficker. Kidane’s guards made him take a freezing shower, leaving him shivering in the desert night. The guards then bound Bedru’s hands behind his back and whipped his torso repeatedly. The wounds took a month to heal, and during this period his clothes remained stuck to his flesh. Kidane maintained a special dislike for Bedru, and beat him with a stick whenever he saw him. “I still have the scars on my back,” Bedru said.

At one point, about a hundred captives in Bani Walid, including Bedru, fled into the desert. Guards pursued the escapees with guns. Doctors Without Borders, which was operating a hospital in the town, later reported that at least fifteen migrants were shot and killed, and dozens were injured. Bedru, whose leg was hurt in the escape, crawled to a nearby mosque, and eventually travelled toward the coast. He was now focussed on escaping traffickers, rather than making it to Europe. Two months later, he was in a U.N. camp in Libya. He was soon repatriated on a flight to Addis Ababa.

Now his former jailer was walking past him in a humdrum Addis Ababa neighborhood. Bedru could not have been more surprised if he’d seen a Bengal tiger strolling by. He followed Kidane on foot. Every time Bedru caught another glimpse of Kidane, he became more confident in his identification. Kidane was wearing a hoodie, jeans, and sandals, just as he had in Bani Walid. Eventually, Kidane stopped at a phone store. Bedru saw two police officers nearby, a man and a woman, and told them why they should arrest Kidane. The female officer knew about the dire situation in Libya’s migrant camps and explained it to her colleague. Bedru then walked up to Kidane and tapped him on the back. Kidane spun around and was shocked to see someone he recognized. “What can I do for you?” he asked Bedru.

The officers stepped in and arrested Kidane, though they didn’t handcuff him. Kidane pleaded his innocence. Then he tried to bribe the police officers, offering them about five hundred dollars. The offer was refused. Kidane, panicked, said that he could get the officers a lot more money, and also take care of Bedru; if they dropped the matter, they could later name their price. Again, he was turned down. Bedru realized that it was the first time he had seen Kidane without a weapon or armed guards. The power in their relationship had shifted. “He was afraid of me,” Bedru recalled.

As the officers led Kidane toward the police station, he suddenly escaped into a crowded marketplace. The male officer chased him and was soon joined by some backup. They eventually overpowered Kidane. Now it was his turn to be detained.

News of the arrest circulated, eventually reaching Meron Estefanos. She reached out to Eritrean contacts in Addis Ababa and learned that Kidane was hardly the only trafficker spending the off-season in the city; many of them had recently been spotted in its cafés and bars. (Ethiopia’s government had recently made it easier for Eritreans to spend extended time there.) Estefanos passed this intelligence to the Regional Operational Center Khartoum, an E.U.-funded police body, based in Sudan, that gathers information on criminal networks involved in the trafficking and abuse of migrants. The rock passed its intelligence to Ethiopian authorities. Within six weeks, the Addis Ababa police had arrested another trafficker who had held and extorted migrants in Bani Walid: Tewelde Goitom, a man known as Welid. He and Kidane had regularly worked together, even sharing guards. They also came from the same town. Whereas Kidane was notorious for beatings, Welid was known as a serial rapist. To Estefanos’s regret, Welid was the final major figure to be apprehended in the investigation. “There were others we were looking for, and I was hoping they would get arrested,” she said. “But then covid hit, and the whole effort stopped.”

Ethiopian prosecutors made cases against both Kidane and Welid, and trials were arranged, but the judicial process was haphazard. Although the pandemic was ongoing, the trial could not proceed through remote hearings, because in Ethiopia witnesses aren’t allowed to appear by video link. This proved problematic, as many potential witnesses were scattered across Africa and Europe. Kidane was charged with only eight counts of trafficking. Fuad Bedru, bafflingly, wasn’t called to give evidence—although he attended as many court hearings as he could. No international monitors were present at the trial. The only Western journalist who covered the proceedings was Sally Hayden, an Irish writer, whose book “My Fourth Time, We Drowned” is a landmark work of reportage about the migrant crisis.

Partway through the trial, in February, 2021, Kidane arrived at an Addis Ababa courthouse in a yellow prison uniform. He was soon ushered into a bathroom, where someone had laid out a change of clothes for him. A few minutes later, he walked out of the courthouse in civilian attire, and disappeared. In all, I was told, Kidane paid about two hundred and fifty thousand dollars in bribes to secure his escape. One of Kidane’s victims told Hayden, “In Ethiopia there is a proverb: ‘Genzeb kale bezemay menged ale.’ This means ‘If there is money, there is a way through the sky.’ ”

Kidane’s escape embarrassed the Ethiopian authorities, but they continued the trial in his absence. In April, 2021, Kidane was found guilty on all counts, and later he was sentenced to life imprisonment. By that time, according to two people with knowledge of Kidane’s whereabouts, he had long since left Ethiopia. For the men and women who had testified against him, the verdict was cold comfort. In Ethiopia, there is little protection for witnesses. Before the trial, the police had put Kidane in lineups and asked his victims to identify him in person, by walking over and touching him. Now the man they had touched was at large. Bedru told me that as these events unfolded, in 2021, he feared that Kidane had both the means and the motivation to seek revenge. As Bedru put it, “He is a bad person, and he is a rich person.”

After Kidane was charged in Addis Ababa, Interpol red notices against both him and Welid were published at the request of the Dutch police, in order to start the process of extraditing them to the Netherlands, where many of their victims now lived. The courtroom escape impressed on the Dutch the urgency of trying Kidane in their own country. The Ethiopian authorities, chagrined, tried to figure out how Kidane had bribed his way to freedom. They didn’t solve the mystery, though they did learn of a wire payment—for a reported twenty-four thousand dollars—that someone in Kidane’s network had sent to Ethiopia, with the intention of dispersing bribes during the trial.

Following Kidane’s escape, Interpol pressed Ethiopia to issue its own red notice against Kidane. In November, 2021, Interpol circulated a report about Kidane’s network, and his likely safe houses, to Sudan, where he had operated; Ethiopia, from which he had escaped; the Netherlands, which was building a case against him; and the U.A.E., where he laundered and spent his money. In fact, according to the Eritrean source familiar with Kidane’s network, Kidane was based in Libya for part of the period after his escape. One persistent rumor placed him in Kufra, the smuggling hub.

In March, 2022, Interpol arranged a meeting of police officers from the four interested countries in Lyon, France. The meeting concluded with a commitment not only to find Kidane but to dismantle his financial network—which meant placing his brother, Henok, under surveillance in Dubai. After the meeting, the U.A.E. police opened a case against Henok. By December, U.A.E. investigators had received a reliable tip that Kidane was now in Sudan. (A police source from another country told me that Emirati investigators confirmed Kidane’s location by tracing phone conversations that he had with his wife, who was travelling from Dubai to meet him; Kidane, apparently feeling out of danger, was making unencrypted calls.) Stephen Kavanagh, the executive director of police services at Interpol, told me that the U.A.E.’s case against Kidane focussed on money laundering, which was easier to prosecute than the Dutch case about Kidane’s crimes in Libya. The U.A.E. pursued Kidane’s arrest.

“Bringing Kidane in for whatever we could—the Al Capone approach—was more important than sequencing,” Kavanagh said. “Even given the more serious charges from our Dutch colleagues.”

According to an officer with knowledge of the operation, the U.A.E. determined that Kidane was in an apartment in Omdurman, a sister city to Khartoum, on the western bank of the Nile. On December 31, 2022, officers from the U.A.E. flew to Khartoum; on New Year’s Day, Emirati officers broke down the reinforced door of the apartment where Kidane was staying. He was entertaining two women, neither of whom was his wife. There were several guns in the apartment, but Kidane fired no shots before surrendering. On the same day, U.A.E. police broke down the door of Henok’s apartment in Dubai, and arrested him, too.

The Emiratis posted a celebratory video on social media announcing that they had led an international effort to catch Kidane—one of the world’s “most wanted criminals.” But since then the Emiratis have stopped discussing the case publicly. Indeed, they refused to answer any of my inquiries about Kidane and Henok. According to a European police source, however, the brothers were both recently convicted in the U.A.E. of money laundering. The officer with knowledge of Kidane’s arrest, though, told me he thinks that the legal process is ongoing. In any event, the Dutch authorities would like to extradite Kidane so that he can stand trial for his more serious crimes alongside Welid, who has been extradited to the Netherlands and whose trial is under way in the city of Zwolle. (Welid denies all allegations against him.) Ironically, it may be that Kidane will first appear in a trial in the Netherlands—not as a defendant but as a witness. Welid’s defense team wants Kidane to testify in the trial in Zwolle. (Welid’s lawyers did not say which aspect of their defense Kidane might bolster.)

The lack of clarity about Kidane’s legal status has frustrated his many victims. In Addis Ababa, Seleshi Girma—the Ethiopian migrant whose abdomen was sliced open—told me that his imprisonment in Bani Walid had left his entire family in dire financial circumstances. He was back in his home country, and unemployed, and he had no way of repaying his relatives. He wanted the people who had been extorted by Kidane to initiate a class-action lawsuit against him, in the hope of recovering some money. “That would be justice,” he said.

Daniel Yalke, who suffered so greatly at Kidane’s hands, feels similarly. He is also back in Addis Ababa. After paying Kidane’s ransom, he eventually made his way to Tunisia, where he attempted to convince a Red Cross employee that he was not Ethiopian but Eritrean, in the hope of being given asylum in Europe. Eventually, Yalke admitted his true identity. “I realized I just wanted my old life back,” he told me. He was sent home on a Red Cross flight. He told me that he is anguished over the financial pain he has caused his family. He is working again as an electrician.

The speakeasy owner in Dubai told me that there is little point in thinking about recovering money from Kidane. Some physical assets could be seized—the houses and the beauty salons—but most of the cash was placed in hawala networks, and would be almost impossible to trace. “The money is with people,” he said.

After the arrest of Kidane and his brother, Interpol said that the police operation had dealt “a significant blow to a major smuggling route towards Europe” and would “protect thousands more from being exploited at the hands of the crime group.” Certainly, the arrests have stopped other migrants from being exploited by Kidane’s enterprise, but they seemed unlikely to do much to prevent the trafficking of African migrants. Kavanagh, the Interpol director, admitted as much to me: “We’re not naïve. More has to be done. There’s no point taking Kidane out and letting others fill the gap.”

Migrant tragedies continue to occur with distressing regularity. This past June, an overcrowded fishing trawler carrying as many as seven hundred and fifty Syrian, Egyptian, Palestinian, and Pakistani people sank off the coast of Greece. Only a hundred and four people were rescued. The trawler had sailed from Libya, which remains—despite all the money that the E.U. has spent on preventative measures—a hub for human trafficking. Tunisia, meanwhile, has become another major destination for migrants wishing to cross the Mediterranean. It may be safer to go there than to Libya, but not much. Tunisia’s President, Kais Saied, has issued tirades against migrants from elsewhere in Africa, saying that their growing presence threatened to turn Tunisia into “a purely African country with no affiliation to Arab and Islamic nations.” Recently, Human Rights Watch reported that migrants who had been intercepted at sea by Tunisia’s Coast Guard were being beaten and robbed by Tunisian officers, and then dumped in the desert with nothing to eat or drink. After one such group of migrants was abandoned in the Sahara, at least twenty-seven died of thirst and exposure. (Tunisia’s government denies such abuses, and Saied says that he is not racist.)

Although Fuad Bedru, the Ethiopian who recognized Kidane in the street, had a horrific experience as a migrant, he was not deterred from attempting to reach Europe again. After Kidane’s escape from the courthouse, Bedru—still determined to improve his prospects, and afraid that Kidane might seek revenge—began making new travel plans. Like many Ethiopians currently attempting to enter Europe without a visa, he chose a different route: after going to Sudan by car, and to Turkey on a cheap flight, he would board a small boat for Greece. He surmised, correctly, that it would be easy to find a fixer in Istanbul who could organize a sea crossing.

Bedru made it to Istanbul last September. A fixer told him to travel to Izmir, on the Turkish coast, and gave him a number to call once he got there. One evening at eight o’clock, Bedru joined forty or fifty others on a dinghy bound for the Greek island of Samos. The boat had only a small outboard motor, which wasn’t powerful enough for so many passengers. None of the migrants were given life jackets. There were two babies on board. When the weather turned bad and the waves rose, people began crying. Water started coming into the boat. Bedru, like most of the migrants, had brought a duffelbag with him. When it seemed possible that the boat would sink, he threw it overboard. The dinghy reached Samos at 6 a.m. Bedru carried with him a light jacket and his phone, and nothing else.

He walked for miles to a U.N. refugee camp, where he was given a space in a tent for four months. In January, 2023, he was transferred to another refugee camp in Greece, where he slept in a shipping container. His plan had always been to reach a rich country in northern Europe, such as the United Kingdom. But that prospect still seemed distant.

Recently, I met Bedru in a southern European country, where he was working at a chicken-processing plant for forty-five euros a day. He asked me not to say exactly where he was, because he didn’t want to alert Kidane’s family or local authorities who might cause him problems.

Bedru was eighteen when he first attempted to come to Europe, and now he was twenty-four. A quarter of his life had been spent on the migrant trail. In his new country, he did not speak the local language, and he had few friends. His work was arduous and poorly paid. I asked him whether he wished he had stayed in Addis Ababa. “No,” he said. “It’s better to be here—even alone.” ♦