In the first essay of this three-part series, I noted that current estimates of the incidence of antidepressant withdrawal range from 1% to 50%; and that patients’ beliefs and hopes, and the availability of alternative treatments, influence how they hear explanations of antidepressant risk.

Now let’s think about where and when patients hear those explanations. Most often it will be just before a prescription is written, in a discussion of “Procedures, Alternatives and Risks”—the PAR conference, as physicians learn it in medical school. The PAR is supposed to present benefits and risks for each of the treatment alternatives a patient might consider. But the PAR process is more complicated than you might think.

Benefits: Managing the Placebo Effect

Antidepressants, on average, add a small increment of improvement over what a placebo offers. For example, in one review, placebo reduced depression symptoms by half or more by an average of 35-40%. For antidepressants, that average was only slightly higher: 42-53%. These results suggest that, on average, most of the value of an antidepressant is coming from its placebo value. After all, we do call these medications “anti-depressants”, right? Perfect.

This is so important, here’s one more striking example. In a study of patients with migraine headache, patients were aware that they might receive a placebo or an anti-migraine medication called Maxalt. Those who were given a placebo but who were told that it was Maxalt had more pain reduction than those who were given Maxalt but told it was a placebo. Even those who were given a placebo and told it was a placebo had a substantial reduction in pain compared to those who received no treatment.

Think about what this means for providers who are trying to offer a patient accurate information about an antidepressant. They know that the patient may indeed choose to take it, so they try to maximize antidepressant’s placebo value. The prescriber must somehow describe a small-to-medium potential benefit and a substantial array of risks, including risk of severe withdrawal symptoms, without undermining the patient’s belief that the pills could help. In other words, even if the antidepressant itself doesn’t directly contribute much, the placebo benefit can be substantial—unless the prescriber has sown doubt in the patient’s mind while trying to be transparent about what can be expected.

You see? Two goals are in direct conflict here: fully informed consent versus maximizing placebo value. An effective prescriber must actively balance these two goals.

Risks: The Nocebo Effect

On the flipside lies similar PAR challenge: patients deserve an accurate account of risk. But too much emphasis on a treatment’s potential risks can increase expectation of those potential problems and thus increase the experience of them (a “nocebo effect”). For example, in a review of trials of COVID-19 vaccine trials, people in the placebo groups had nearly as many adverse effects (headache, fatigue, nausea, muscle pain) as people in the active vaccine group, but only with the first dose. With the second dose, adverse effects were far higher in the vaccine group, presumably because vaccine was indeed inducing an immune response leading to those symptoms, while the placebo group, having weathered the first dose, had lower expectations for problems.

Therefore, an effective prescriber must convey information about antidepressants’ risks without creating too strong an expectation for such problems. It’s just like the balancing act required to maximize placebo value, but in reverse: in this case, minimizing expectations while conveying accurate information.

Further, there are a lot of side effects and risks to consider. Offering a litany of all known concerns would be too lengthy: substantial risks could be overshadowed by the long list of little ones. Instead, the prescriber chooses which risks to present. Generally, this includes any risks that are dangerous, and any that are extremely common. (In addition, I often present the risks that a patient is likely to run into on the internet with even a simple search. I’d rather they hear about these risks from me, where I can shape how they sound.)

Thus, in the PAR process, two goals are in direct conflict: fully informed consent versus maximizing the medication’s value. I hope this is starting to sound nearly impossible to you. In the face of this challenge, I suspect prescribers likely tip this complex balancing act toward the treatment they think is most likely to help their patient. (Decreasing patient autonomy, but from benevolent motivation.) This means the prescribers’ beliefs about benefits and risks have a very strong impact on how a treatment is described.

Prescribers Are Human Too

Humans use shortcuts to estimate risks, especially in conditions of uncertainty. These shortcuts are often wildly inaccurate. For example, the “availability” shortcut: if an example of a particular event comes quickly to mind, we think the event is common; whereas if an example is hard to find in memory, we think the event is rare. This obviously leads to errors when the event is striking and dramatic (e.g. a terrorist attack) or off one’s radar (e.g. treatment-resistant tuberculosis).

Imagine how this affects a clinician’s thinking. If one of their patients recently had a great response to a particular antidepressant, then if they’re like most humans, the clinician will evaluate the benefits of that antidepressant more positively than if it’s been a long time since seeing such a response. Likewise, if they haven’t recently seen a patient have significant withdrawal symptoms (perhaps because their patient left and never told them about it; or perhaps because they didn’t ask), then if they’re like most humans, the clinician will evaluate the risk of antidepressants with less concern than if they saw a recent severe case.

In other words, prescribers are subject to common cognitive errors (patients too). These include confirmation bias (more likely to hear and see results that support one’s previous beliefs); the well-traveled road effect (a repeatedly used tool, such as an antidepressant, is more likely to be used again); and many others.

Too Many Options

Prescribers also fear that if they presented the entire menu of options, they’d be sitting with the patient for many minutes, explaining each treatment and its pros and cons. Some of the treatment options for depression are quite complicated: transcranial magnetic stimulation, for example; or how to use a light box correctly. The clinician might regard some treatment options as ill-suited to that particular patient: ketamine, for example, in a patient with bipolar disorder (because research has only just recently been expanded to include bipolar depression). Thus, prescribers narrow the range of options considered, focusing on those they think are most likely to help. Here, the balancing act is self-preservation, if you will, versus patient autonomy.

The Process Is Actually Backwards

Thus… while attempting to balance information to maximize placebo value and minimize nocebo effects; and while being human (subject to cognitive biases, error-prone mental shortcuts, and desiring self-preservation); in actual practice, the consideration of Procedures, Alternatives and Risks occurs in reverse: the prescriber decides what one or two treatments might be best and then presents those alternatives to the patient. Maybe three. Only rarely would the full smorgasbord be offered. In other words, the decision-making begins with the provider, not the patient.

To partially reverse this sequence of events in favor of greater patient involvement, multiple groups have advocated a process referred to as Shared Decision-Making (SDM) (including Britain’s National Health Service, in their most recent guidelines.

Shared Decision-Making

SDM doesn’t necessarily mean sharing the entire smorgasbord of treatment options, although that’s one way to start. It means sharing the decision-making process after disclosing the risks and benefits of at least a few treatment options. Unfortunately, although treatment results are better when patients are involved in decision-making, healthcare professionals do not easily adopt SDM and even institutional efforts to make it routine have often failed. One of the reasons: creating informative Patient Decision Aids (PDAs) is difficult.

Patient Decision Aids

PDAs are supposed to help providers share treatment decision-making, including paper or video or digital educational materials focused on a specific health problem. They aim to empower patients by presenting information in an understandable manner, hopefully decreasing confusion about options and helping make sure that treatments selected truly align with patients’ preferences and values. But in practice, they haven’t become common. Here are two reasons why.

First: PDAs are like the consensus statements from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: for matters of controversy (e.g. whether to say “phase out” or “phase down” fossil fuels”), PDAs tend to present the most conservative views.

Perhaps that’s why so few PDAs about depression say anything about antidepressant withdrawal: it’s too controversial? In one of the largest PDA libraries available, there are seven PDAs on depression. How many of them address antidepressant withdrawal? Just one, and only if you count this description: “Quitting your medicine all at once can make you feel sick, as if you had the flu (headache, dizziness, light-headedness, nausea or anxiety.”

Secondly, providers are hesitant to use PDAs because they interfere with the sensitive and complex process I just described: balancing the need for information transparency with the need to maximize a treatment’s value by maximizing patient confidence in whatever treatment they choose. Even a well-balanced, conservative PDA could tilt a patient away from a treatment that could be very helpful for them. So rather than start from a generic presentation of the full smorgasbord of treatment options, clinicians tend to focus on a few, presenting those options in the best possible light.

Unfortunately, this leaves the PAR vulnerable to the profound influence the pharmaceutical industry has had, and continues to have, on clinicians’ concepts of “best options”. In particular, the entire concept of “FDA-approved” treatments is an egregious twist of public trust: since companies must have FDA approval to market a new product, and the only way to get such approval is to run randomized trials that cost millions of dollars, only new expensive drugs can earn FDA approval. Generic drugs do not because there is no financial incentive to run the necessary large trials. Thus, new drugs are loudly touted as “FDA approved”, which obviously suggests, even without stating it as such, that all the other treatments patients might consider are “not approved”, which certainly sounds like “disapproved”. Not the right starting point for creating a good placebo effect.

The pharmaceutical industry has many other means of influencing clinicians’ concepts of “best options”: attractive, personable “reps” make office visits, with samples alone a sufficient inducement (which many clinicians use to allow a few patients access to a new treatment they cannot otherwise afford). So, no question, “pharma” has strong influence. Some clinicians work actively against this influence: no office visits for reps, no samples, staying skeptical about industry influence on published articles, presuming that randomized trials are slanted in favor of the company’s drug (especially if they sponsored the study), waiting for broad clinical experience (not company publications) to show that a new medication really gets better results than inexpensive generics, and believing that only long experience will reveal the true risks. Granted, not all clinicians are thus cautious.

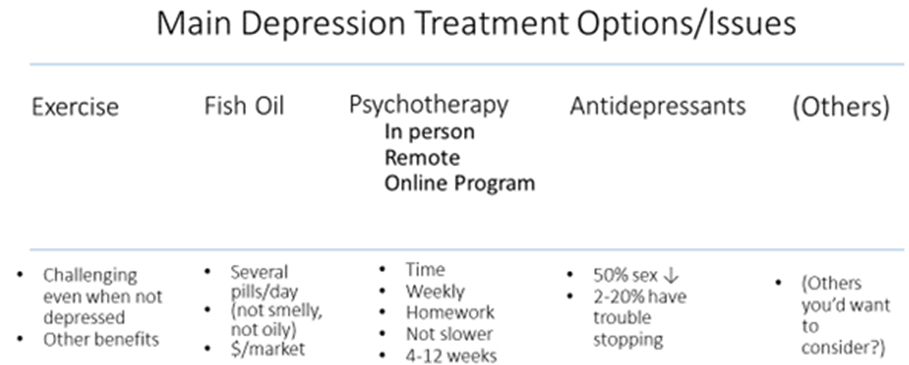

To avoid clinician-narrowing of options, moving too quickly to antidepressants and offering only a choice of which antidepressant to take, here’s a broad PDA. It’s just a first draft, because the next step in developing PDAs is to seek input from users: patients and providers. Then revise, and revise again—hopefully not becoming so watered down in seeking consensus that no one wants to use it!

Just as an example, then:

I used “2-20% have trouble stopping”. That’s an example of consensus seeking. If it elicits equal criticism—too low and too high—then perhaps it’s about right for now, until we have more data.

Conclusion

By examining placebo effects, nocebo effects, and recognizing the inevitable effects of patients’ and providers’ beliefs and biases, I hope to have convinced you that a balanced PAR is difficult, but not entirely impossible. However, imagine doing this in a busy primary care practice, where most antidepressants are started. Tried to get an appointment lately? Tried to find a new PCP lately?

Otherwise, I don’t have great solutions to offer. Why write all this, then? Two reasons: first, I hope to show readers that there are important reasons why the risk of antidepressant withdrawal has not been well explained to people before they start them. These reasons must be considered by anyone who wishes to change the way antidepressants are prescribed.

Secondly, I have a hunch to share. What if we could identify in advance the patients who will have severe withdrawal problems? They could be given much stronger warnings about this risk. And if they’re already on an antidepressant, they could be given careful tapering instructions about taking slow small steps down.

In the last of these three essays, I’ll describe my hunch and suggest some of its implications.