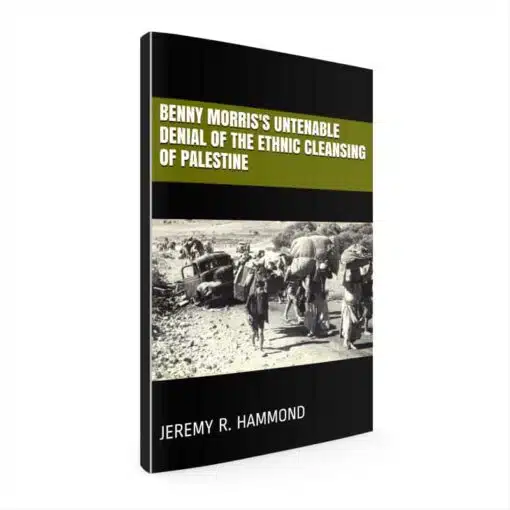

The Israeli historian Benny Morris has been very vocal of late in denying that Palestine was ethnically cleansed of Arabs in order for the “Jewish state” of Israel to be established. In a series of articles in the Israeli daily Haaretz, Morris has debated the question with several of his critics who contend that ethnic cleansing is precisely what occurred. Not so, argues Morris. So who’s right?

It’s worth noting at the outset that, while such a debate exists in the Israeli media, the US media remains, as ever, absolutely silent on the matter. Americans who get their information about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict only from the nightly news or papers like the New York Times and Washington Post would never even know that there is a discussion about it. Not only that, but they would have absolutely no familiarity at all with the idea that Palestine was ethnically cleansed of most of its Arab inhabitants in 1948. That this occurred (or even that this might have occurred) is entirely absent from the discussion; it is simply wiped from history altogether, in the narrative of the conflict propagated by the US media.

Even in those rare instances when the mainstream media outlets do refer to the expulsion and flight of Arabs from their villages, it is characterized as only as an unfortunate but unintended consequence of a war started by the neighboring Arab states to wipe the new state of Israel off the map—a narrative that is not merely over-simplified, but false.[1]

So was Palestine ethnically cleansed in 1948? The debate between Benny Morris and his interlocutors provides a unique occasion to clear up several myths and misconceptions about what actually happened during the 1948 war. An examination of the arguments Morris presents to deny its occurrence is highly instructive, and offers an opportunity to settle the matter once and for all—and, in doing so, to finally move the discussion about how to achieve peace between Israelis and Palestinians forward.

The Debate

It started when Daniel Blatman, an Israeli historian and head of the Institute for Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, penned an op-ed for the Israeli daily Haaretz stating that ethnic cleansing “is exactly what happened in 1948.” To support this, Blatman cited Benny Morris: the Israeli historian, Blatman wrote, “determined that most of the Arabs in the country, over 400,000, were encouraged to leave or expelled in the first stage of the war—even before the Arab nations’ armies invaded.”[2]

That prompted a response from Morris, who wrote an op-ed of his own titled “Israel Conducted No Ethnic Cleansing in 1948”. In it, he contends that Blatman “distorts history when he says the new State of Israel, a country facing invading armies, carried out a policy of expelling the local Arabs.” And Blatman “betrayed his profession”, Morris further charged, “when he attributed to me things I have never claimed and distorted the events of the 1948 war.”

Central to Morris’s argument is that “Blatman ignores the basic fact that the Palestinians were the ones who started the war when they rejected the UN compromise plan and embarked on hostile acts in which 1,800 Jews were killed between November 1947 and mid-May 1948.” Moreover, the neighboring Arab states had “threatened to invade even before the UN resolution was passed on November 29, 1947, and before a single Arab had been uprooted from his home.” Even prior to the adoption of General Assembly Resolution 181, which recommended partitioning Palestine into separate Arab and Jewish states, the Arab states had continuously declared their intent “to attack the Jewish state when the British left.”

He acknowledges that prior to the Zionists’ declaration of the existence of Israel on May 14, 1948, and the subsequent introduction of Arab states’ regular armies into the conflict, a few hundred thousand Arabs (though a number “apparently smaller” than the figure of 400,000 cited by Blatman) “were expelled from their homes and forced to flee”.

How can it be true that, on one hand, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were forced from their homes and never allowed to return, yet also true, on the other, that there was no ethnic cleansing?

Morris attempts to reconcile the apparent contradiction by arguing that “at no stage of the 1948 war was there a decision by the leadership of the Yishuv [the Jewish community] or the state to ‘expel the Arabs’”. In other words, it’s true that many Arabs were indeed expelled, but this was not the result of an official policy of the Zionist leadership.

“It’s true that in the 1930s and early ‘40s”, Morris further acknowledges, “David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann supported the transfer of Arabs from the area of the future Jewish state. But later they supported the UN decision, whose plan left more than 400,000 Arabs in place.

“It’s also true that from a certain point during the war, Ben-Gurion let his officers understand that it was preferable for as few Arabs as possible to remain in the new country, but he never gave them an order ‘to expel the Arabs.’”

And, true, there was an “atmosphere of transfer that prevailed in the country beginning in April 1948”, but this “was never translated into official policy—which is why there were officers who expelled Arabs and others who didn’t. Neither group was reprimanded or punished.

“In the end, in 1948 about 160,000 Arabs remained in Israeli territory—a fifth of the population.”

Furthermore, “on March 24, 1948, Israel Galili, Ben-Gurion’s deputy in the future Defense Ministry and the head of the Haganah, ordered all the Haganah brigades not to uproot Arabs from the territory of the designated Jewish state. Things did change in early April due to the Yishuv’s shaky condition and the impending Arab invasion. But there was no overall expulsion policy—here they expelled people, there they didn’t, and for the most part the Arabs simply fled.”

Morris acknowledges that the Zionist leadership in mid-1948 “adopted a policy of preventing the return of refugees”, but asserts this was “logical and just” on the grounds that these were the “same refugees who months and weeks earlier had tried to destroy the state in the making.”

What happened in 1948 does not fit the definition of “ethnic cleansing”, Morris concludes. The Arab states, on the other hand, “carried out ethnic cleansing and uprooted all the Jews, down to the last one, from any territory they captured in 1948”, while the Jews “left Arabs in place in Haifa and Jaffa”, among other places.[3]

That wasn’t the end of the discussion. Blatman responded in turn with an op-ed titled “Yes, Benny Morris, Israel Did Perpetrate Ethnic Cleansing in 1948”. In it, he writes that, “On March 10, 1948, the national Haganah headquarters approved Plan Dalet, which discussed the intention of expelling as many Arabs as possible from the territory of the future Jewish state.”

With regard to Morris’s denial that what occurred fits the definition of “ethnic cleansing”, Blatman quotes the prosecutor in the trial of Radovan Karadzic, a Bosnian-Serb leader convicted for the ethnic cleansing of Muslims in Bosnia:

In ethnic cleansing . . . you act in such a way that in a given territory, the members of a given ethnic group are eliminated. . . . You have massacres. Everybody is not massacred, but you have massacres in order to scare those populations. . . . Naturally, the other people are driven away. They are afraid . . . and, of course, in the end these people simply want to leave. . . . They are driven away either on their own initiative or they are deported. . . . Some women are raped and, furthermore, often times what you have is the destruction of the monuments which marked the presence of a given population . . . for instance, Catholic churches or mosques are destroyed.

In other words, contrary to Morris’s argument, it doesn’t follow that, since there is no document in which the Zionist leadership explicitly outlined a plan to expel all Arabs or in which military commanders were instructed to do so, therefore what occurred was not ethnic cleansing. What the prosecutor describes is exactly what happened in 1948, Blatman notes: “Implied instructions, silent understandings, sowing fear among the population whose flight is the objective; the destruction of the physical presence left behind.”

Blatman quotes from Morris’s book The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949:

The attacks of the Haganah and the Israel Defense Forces, expulsion orders, the fear of attacks and acts of cruelty on the part of the Jews, the absence of assistance from the Arab world and the Arab Higher Committee, the sense of helplessness and abandonment, orders by Arab institutions and commanders to leave and evacuate, in most cases was the direct and decisive reason for the flight—an attack by the Haganah, Irgun, Lehi or the IDF, or the inhabitants’ fear of such an attack.

Blatman adds, “The expulsions were not war crimes, says Morris, because it was the Arabs who started the war. In other words, hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians who belong to the side that began the fighting have to be expelled. Maybe Morris would agree that the genocide carried out by the Germans against the Herero in 1904–1908 was justified since, after all, the Herero began the rebellion against German colonialism in Namibia.”[4]

Next to weigh in on the debate was Steven Klein, a Haaretz editor and adjunct professor at Tel Aviv University’s International Program in Conflict Resolution and Mediation. Klein notes how Morris himself, in a 1988 essay titled “The New Historiography”, had explained how under Plan D, the Zionist forces “cleared various areas completely of Arab villages”, and how “Jewish atrocities . . . and the drive to avenge past misdeeds also contributed significantly to the exodus.”

And in his book Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–2001, “Morris observed that Ben-Gurion’s views on ‘transfer as a legitimate solution to the Arab problem’ did not change after he publicly declared support for forced expulsions in the 1930s, but that ‘he was aware of the need, for tactical reasons, to be discreet.’ Thus, so it seemed, he explained how Ben-Gurion could be responsible for the expulsion of many of the 700,000 Palestinian Arabs without ever issuing an order to that effect.”

Then in a 2004 Haaretz interview with journalist Ari Shavit, Morris had said, “A Jewish state would not have come into being without the uprooting of 700,000 Palestinians. Therefore it was necessary to uproot them.”

“Morris, of course, is welcome to change his political view”, Klein continues. “But he, like any other historian, must understand that he has left a paper trail that tells a substantially different narrative than the one he now advocates. The Benny Morris of 2016 seems to be doing what he once accused the ‘old historians’ of doing—interpreting history and downplaying Israeli misdeeds in order to defend Israel’s legitimacy.”[5]

Next to chime in on the debate was Ehud Ein-Gil, who points out in his own Haaretz op-ed that among the Arabs who were allowed to remain were “15,000 Druze who had allied with Israel, 34,000 Christians, whom Israel treated decently so as not to anger its Western allies, and some Bedouin Muslim villages, whose leaders had allied with Israel or with their Jewish neighbors.

“Of the 75,000 Muslims who remained (less than 15 percent of the prewar number), tens of thousands were internally displaced—people who had fled their villages or were expelled from them and have not been allowed to return to their homes to this day.”

“Morris is right”, Ein-Gil continues, “when he mentions the ‘atmosphere of transfer’ that gripped Israel from April 1948, but he errs when he claims that this atmosphere was never translated into official policy.” He quotes the orders given to commanders in Plan D to either destroy villages or encircle and then mount “search-and-control operations” within them and, in the event of resistance, to expel all inhabitants.[6]

Finally, Morris responded once more to his critics with a Haaretz article titled “‘Ethnic Cleansing’ and pro-Arab Propaganda”, in which he characterizes their articles as not reflecting “a serious way of writing history.”

His own “opinions about the history of 1948 haven’t changed at all”, Morris asserts. He maintains that “Some Palestinians were expelled (from Lod and Ramle, for example), some were ordered or encouraged by their leaders to flee (from Haifa, for example) and most fled for fear of the hostilities and apparently in the belief that they would return to their homes after the expected Arab victory.

“And indeed, beginning in June, the new Israeli government adopted a policy of preventing the return of refugees—those same Palestinians who fought the Yishuv, the prestate Jewish community, and tried to destroy it.”

Morris contends, “In 1947–1948 there was no a priori intention to expel the Arabs, and during the war there was no policy of expulsion. There are clearly Israel-hating ‘historians’ like Ilan Pappe and Walid Khalidi, and perhaps also Daniel Blatman, going by what he has said, who see the Haganah’s Plan Dalet of March 10, 1948, as a master plan for expelling the Palestinians. It isn’t.”

Rather, Plan D “was intended to craft strategy and tactics for the Haganah to maintain its hold on strategic roads in what was to become the Jewish state. It also sought to secure the borders in the run-up to the expected Arab invasion following the departure of the British. Blatman’s contention that Plan Dalet ‘discussed the intention of expelling as many Arabs as possible from the territory of the future Jewish state’ is a malicious falsification. These are the words of a pro-Arab propagandist, not of a historian.”

Furthermore, Plan D “explicitly states that the inhabitants of villages that fight the Jews should be expelled and the villages destroyed, while neutral or friendly villages should be left untouched (and have forces garrisoned there).

“As for Arab neighborhoods in mixed cities, the Haganah field commanders ordered that the Arabs of the outlying neighborhoods be transferred to the Arab centers of those cities, like Haifa, not expelled from the country.”

Morris contends that, “if there had been a master plan and a policy of ‘expelling the Arabs,’ we would have found indications of this in the various operational orders to the combat units, and in the reports to the command headquarters, like ‘We carried out the expulsion in accordance with the master plan’ or ‘with Plan Dalet.’ There are no such mentions.”

True, “there was an ‘atmosphere of transfer,’” but this was “understandable in light of the circumstances: constant attacks by Palestinian militias over four months and the expectation of an impending invasion by the Arab armies aimed at annihilating the Jewish state to be and perhaps the people as well.”

This “necessitated occupation and the expelling of villagers who ambushed, sniped at and killed Jews along the borders and the main roads.” Moreover, “the vast majority of Arabs fled, and the officers of the Haganah/IDF had no need to face the decision of whether to expel them.”[7]

Points of Agreement

While there are a number of points on which Morris and his critics heatedly disagree, it’s imperative to begin by highlighting those facts that aren’t in dispute.

First and foremost, it’s completely uncontroversial that hundreds of thousands of Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes by the Zionist forces during the 1948 war—about 700,000, according to Morris, by the time it was done.

Also uncontroversial is the fact that much of this flight and expulsion occurred well before the neighboring Arab states sent in their armies following the Zionists’ declaration of the existence of the state of Israel on May 14, 1948.

In his book The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949, Morris estimates the number of Arabs made refugees prior to May 14 at somewhere between 200,000 and 300,000. In his book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Israeli historian Ilan Pappé writes, “There were in fact 350,000 if one adds all of the population from the 200 towns and villages that were destroyed by 15 May 1948.”[8] This is consistent with Morris’s remark that the number was “apparently smaller” than 400,000.

Another uncontroversial fact is that there was a prevailing “atmosphere of transfer” among the Zionist leadership—with “transfer” being a euphemism for the forced displacement of Arabs from their homes. As Morris notes in his book 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War, “an atmosphere of what would later be called ethnic cleansing prevailed”, and, to be sure, “much of the country had been ‘cleansed’ of Arabs” by the end of the war.[9]

Indeed, the idea that the Arabs would have to go was an assumption inherent in the ideology of political Zionism. The Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl, who is considered the father of the movement, outlined the Zionist project in a pamphlet titled The Jewish State in 1896.[10] A year prior, he had expressed in his diary the need to rid the land of its Arab majority: “We shall have to spirit the penniless population across the border, by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our own country. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.”[11]

In 1937, the British Peel Commission proposed that Palestine be partitioned into separate Jewish and Arab states, but there was a problem: there would remain an estimated 225,000 Arabs in the area proposed for the Jewish state. “Sooner or later there should be a transfer of land and, as far as possible, an exchange of population”, the Commission concluded. It proceeded to draw attention to the “instructive precedent” of an agreement between the governments of Greece and Turkey in the aftermath of the Greco-Turkish War of 1922 that determined that “Greek nationals of the Orthodox religion living in Turkey should be compulsorily removed to Greece, and Turkish nationals of the Moslem religion living in Greece to Turkey.”

The Commission expressed its hope “that the Arab and the Jewish leaders might show the same high statesmanship as that of the Turks and the Greeks and make the same bold decision for the sake of peace.”[12]

Of course, the Commission was not unmindful of “the deeply-rooted aversion which all Arab peasants have shown in the past to leaving the lands which they have cultivated for many generations. They would, it is believed, strongly object to a compulsory transfer . . . .”[13]

As Morris notes in 1948, “The fact that the Peel Commission in 1937 supported the transfer of Arabs out of the Jewish state-to-be without doubt consolidated the wide acceptance of the idea among the Zionist leaders.”[14] “Once the Peel Commission had given the idea its imprimatur, . . . the floodgates were opened. Ben-Gurion, Weizmann, Shertok, and others—a virtual consensus—went on record in support of transfer at meetings of the JAE [Jewish Agency Executive] at the Twentieth Zionist Congress (in August 1937, in Zurich) and in other forums.”[15] Chaim Weizmann, for example, in January 1941 told the Soviet ambassador to London, Ivan Maiskii, “If half a million Arabs could be transferred, two million Jews could be put in their place.”[16]

The Zionist leader who would become Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, after the Peel Commission had recommended the “compulsory transfer” of Arabs, expressed his acceptance of the partition plan as a pragmatic first step toward the ultimate goal of establishing a Jewish state over all of the territory of Palestine. On October 5, 1937, he wrote to his son (underlined emphasis in original):

Of course the partition of the country gives me no pleasure. But the country that they are partitioning is not in our actual possession; it is in the possession of the Arabs and the English. What is in our actual possession is a small portion, less than what they are proposing for a Jewish state. If I were an Arab I would have been very indignant. But in this proposed partition we will get more than what we already have, though of course much less than we merit and desire. . . . What we really want is not that the land remain whole and unified. What we want is that the whole and unified land be Jewish. A unified Eretz Israeli [sic] would be no source of satisfaction for me—if it were Arab.

Acceptance of “a Jewish state on only part of the land”, Ben-Gurion continued, was “not the end but the beginning.” In time, the Jews would settle the rest of the land, “through agreement and understanding with our Arab neighbors, or through some other means” (emphasis added). If the Arabs didn’t acquiesce to the establishment of a Jewish state in the place of Palestine, then the Jews would “have to talk to them in a different language” and might be “compelled to use force” to realize their goals.[17]

“My approach to the solution of the question of the Arabs in the Jewish state”, said Ben-Gurion in June 1938, “is their transfer to Arab countries.” The same year, he told the Jewish Agency Executive, “I am for compulsory transfer. I do not see anything immoral in it.”[18]

The idea of partitioning Palestine was resurrected by the UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP), which had drawn up the plan endorsed by the UN General Assembly in Resolution 181 on November 29, 1947. This plan, too, contained the inherent problem of a sizable population of Arabs who would remain within the boundaries of the proposed Jewish state. Benny Morris documents the attitude of the Zionist leadership with respect to this dilemma:

The Zionists feared that the Arab minority would prefer, rather than move to the Arab state, to accept the citizenship of the Jewish state. And “we are interested in less Arabs who will be citizens of the Jewish state,” said Golda Myerson (Meir), acting head of the Jewish Agency Political Department. Yitzhak Gruenbaum, a member of the Jewish Agency Executive and head of its Labor Department, thought that Arabs who remained in the Jewish state but were citizens of the Arab state would constitute “a permanent irredenta.” Ben-Gurion thought that the Arabs remaining in the Jewish state, whether citizens of the Arab or Jewish state, would constitute an irredenta—and in the event of war, they would become a “Fifth Column.” If they are citizens of the Arab state, argued Ben-Gurion, “[we] would be able to expel them,” but if they were citizens of the Jewish state, “we will be able only to jail them. And it is better to expel them than jail them.” So it was better not to facilitate their receipt of Jewish state citizenship. But Ben-Gurion feared that they would prefer this citizenship. Eli‘ezer Kaplan, the Jewish Agency’s treasurer, added: “Our young state will not be able to stand such a large number of strangers in its midst.”[19]

In sum, there was a consensus that such a sizable population of Arabs within the borders of their desired “Jewish state” was unacceptable. The events that followed must be analyzed within the context of this explicit understanding among the Zionist leadership that, one way or another, a large number of Arabs would have to go.

Who Started the War?

One of Morris’s main arguments underscoring his denial of ethnic cleansing is that it was the Arabs, not the Jews, who started the war after having rejected the UN partition plan. He points to hostile actions by the Arabs between the end of November 1947 and May 1948, but, of course, there were also hostile actions by the Jews during this same period. So is there a particular incident Morris can point to as having marked the initiation of these hostilities?

In fact, in his book 1948, he does point to a specific event. Early in the morning on November 30—the day after Resolution 181 was adopted in the UN General Assembly—an eight-man armed band from Jaffa ambushed a Jewish bus near Kfar Syrkin, killing five. Half an hour later, the gang attacked a second bus, killing two more. “These were the first dead of the 1948 War”, Morris writes.

Yet Morris also acknowledges that these attacks were almost certainly “not ordered or organized by” the Arab Palestinian leadership. And “the majority view” in the intelligence wing of the Haganah—the Zionists’ paramilitary organization that later became the Israel Defense Forces (IDF)—“was that the attackers were driven primarily by a desire to avenge” a raid by the Jewish terrorist group Lehi, also known as the Stern Gang, on an Arab family ten days prior. Lehi “had selected five males of the Shubaki family and executed them in a nearby orange grove” as an act of revenge for the apparently mistaken belief that the Shubakis had informed the British authorities about a Lehi training session that prompted a British raid on the group in which five Jewish youths were killed.[20]

So why wasn’t the murder of five Arabs by the Jewish terrorist organization the initiating act of hostility marking the start of the 1948 war, in Morris’s account?

Clearly, to try to assess responsibility for the war by pinpointing this or that incident of tit-for-tat violence is an exercise in futility. Moreover, apart from overlooking the Zionists’ own acts of hostility, Morris’s claim that the Arabs started the war serves to remove the mutual hostilities that broke out in the wake of the General Assembly’s adoption of Resolution 181 from their larger context—and it is only within that larger context that a proper assessment of which side bore greater responsibility for the war can be made.

As in the above example, Morris tends to portray Jewish violence against Arabs as always being preceded by Arab violence against Jews—even though, as just illustrated, it was equally true that the Arab violence had, in turn, been preceded by Jewish violence. Elsewhere, in contrast to how he characterizes Arab violence, Morris describes unambiguous war crimes committed by the Zionist forces as merely “mistakes”.

Included among the Haganah’s “mistakes” was an attack on December 18, 1947, on the village of Khisas. Carried out with the approval of Yigal Allon, the commander of the Palmach (an elite unit within the Jewish army), Zionist forces invaded the village and indiscriminately murdered seven men, a woman, and four children. Morris describes this as a “reprisal” for the murder of a Jewish cart driver earlier that day, even though, as he superfluously notes, “None of the dead appear to have been involved in the death of the cart driver.”[21]

Another of the Haganah’s “mistakes” occurred on the night of January 5, 1948, when Zionist forces entered the West Jerusalem neighborhood of Katamon and bombed the Semiramis Hotel, killing twenty-six civilians, including a government official from Spain. “The explosion triggered the start of a ‘panic exodus’ from the prosperous Arab neighborhood.” The British were furious, and Ben-Gurion subsequently removed the officer responsible from command.[22]

“But generally”, Morris continues, “Haganah retaliatory strikes during December 1947–March 1948 were accurately directed, either against perpetrators or against their home bases”—meaning the Arab villages where they lived. Thus, according to Morris’s own criteria, when the Haganah attacked an Arab village that happened to be home to one or more combatants and proceeded to go about “accurately” killing innocent civilians and destroying their homes, this was by no means a “mistake”.

Instructively, Morris quotes a document from the intelligence wing of the Haganah on the consequences of what he describes as the “Jewish reprisals” that occurred during those months: “The main effect of these operations was on the Arab civilian population” (emphasis added), the Haganah noted, including “the destruction of their houses” and psychological trauma. Among other consequences, “The Jewish attacks forced the Arabs to tie down great forces in protecting themselves” (emphasis added).[23] Thus Morris’s characterization of Arabs as the aggressors and the Haganah as being on the defensive throughout this period is contradicted by his own account, citing primary source evidence that precisely the opposite was true.

Indeed, Morris goes into considerable detail documenting how, in his own summation, “the Yishuv had organized for war. The Arabs hadn’t.”[24]

Morris’s characterization of the Arabs as always being the aggressors and the Jews as being on the defensive, despite occasional “mistakes” such as those just noted, extends well prior to the onset of the 1948 war. While Lehi’s murder of five members of the Shubaki family on November 20 seems to fit Morris’s criteria for a “mistake”, he could, in turn, also point to Arab attacks on Jews that had occurred well prior to that incident.

He writes, for example, that in the spring and summer of 1939 the Irgun Zvai Leumi, “which had been formed by activist breakaways from the Haganah, subjected the Arab towns to an unnerving campaign of retaliatory terrorism, with special Haganah units adding to the bloodshed through selective reprisals” (emphasis added).[25]Once again we see that, while Morris doesn’t try to justify such acts of terrorism, he does characterize them as only occurring in retaliation for earlier acts of aggression by Arabs.

Indeed, Morris could go back a decade prior, within this exercise of trying to pinpoint responsibility for the initiation of such tit-for-tat violence, and point to the 1929 massacre of Jews in Hebron; or, further, to May 1921, when Arab mobs murdered Jews in Jaffa; or further still, to April 1920, when Arab rioters killed five Jews in Jerusalem.

There is no dispute that these earlier incidences of violence were initiated by Arabs. But the question remains of why they occurred. Did these murderous attacks reflect an inherent hatred of Jews among the Arab population? Or is there some other context that the debate Morris has had with his critics is still missing?

Those were questions the British occupiers asked themselves and conducted inquiries to try to answer. The inquiry into the outbreak of violence in 1921, the Haycraft Commission, determined that “there is no inherent anti-Semitism in the country, racial or religious. We are credibly assured by educated Arabs that they would welcome the arrival of well-to-do and able Jews who could help to develop the country to their advantage of all sections of the community.”[26] The outbreaks, rather, reflected the growing apprehension and resentment among the Arabs toward the Zionist project to reconstitute Palestine into a “Jewish state”—and in so doing to displace or otherwise disenfranchise and the land’s majority Arab population.

Nor were the Arabs’ fears unfounded; indeed, the Zionists were quite open about their intentions. When the acting Chairman of the Zionist Commission was interviewed, for example, “he was perfectly frank in expressing his view of the Zionist ideal. . . . In his opinion there can only be one National Home in Palestine, and that a Jewish one, and no equality in the partnership between Jews and Arabs, but a Jewish predominance as soon as the numbers of that race are sufficiently increased.”[27]

The Shaw Commission inquiring into the cause of the 1929 violence arrived at the same conclusion and further observed:

In less than ten years three serious attacks have been made by Arabs on Jews. For eighty years before the first of these attacks there is no recorded instance of any similar incidents. It is obvious then that the relations between the two races during the past decade must have differed in some material respect from those which previously obtained. Of this we found ample evidence. The reports of the Military Court and of the local Commission which, in 1920 and in 1921 respectively, enquired into the disturbances of those years, drew attention to the change in the attitude of the Arab population towards the Jews in Palestine. This was borne out by the evidence tendered during our enquiry when representatives of all parties told us that before the War the Jews and Arabs lived side by side if not in amity, at least with tolerance, a quality which to-day is almost unknown in Palestine.[28]

Morris likewise notes in 1948 that the attacks were chiefly motivated by “the fear and antagonism toward the Zionist enterprise”: “The bouts of violence of 1920, 1921, and 1929 were a prelude to the far wider, protracted eruption of 1936–1939, the (Palestine) Arab Revolt. Again, Zionist immigration and settlement—and the prospect of the Judaization of the country and possibly genuine fears of ultimate displacement—underlay the outbreak.”[29]

As Jewish Agency chairman David Ben-Gurion wrote to the director of the agency’s Political Department, Moshe Shertok, in 1937, “What Arab cannot do his math and understand that immigration at the rate of 60,000 a year means a Jewish state in all of Palestine?”[30]

As Morris also documents, Ben-Gurion understood the Arab perspective perfectly well. With respect to the 1936–1939 Arab Revolt, Ben-Gurion told his colleagues, “We must see the situation for what it is. On the security front, we are those attacked and who are on the defensive. But in the political field we are the attackers and the Arabs are those defending themselves. They are living in the country and own the land, the village. We live in the Diaspora and want only to immigrate [to Palestine] and gain possession of [lirkosh] the land from them.”[31]

Ben-Gurion told Zionist leader Nahum Goldmann years later, after the establishment of Israel, “Why should the Arabs make peace? If I was an Arab leader I would never make terms with Israel. That is natural: We have taken their country. Sure, God promised it to us, but what does that matter to them? Our God is not theirs. We come from Israel, it’s true, but two thousand years ago, and what is that to them? There has been anti-Semitism, the Nazis, Hitler, Auschwitz, but was that their fault? They only see one thing: We have come here and stolen their country. Why should they accept that?”[32]

Another aspect of Morris’s assessment that warrants emphasis is how he takes for granted that the UN partition plan was an equitable solution and that it was unreasonable of the Arabs to have rejected it. While accusing his critics of “pro-Arab propaganda”, this assumption reveals his own demonstrable prejudice toward the Palestinians. In truth, the UN partition plan was preposterously inequitable. Here, too, some additional historical background helps illuminate the context in which Resolution 181 was adopted, as well as the questions of why the 1948 war started and who bore greater responsibility for it.

The Zionist Mandate for Palestine

During the First World War, the British came to occupy the territory of Palestine, having conquered it from the defeated Ottoman Empire. On November 2, 1917, British Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour sent a letter to financier and representative of the Zionist movement Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild that contained a declaration approved by the British Cabinet. The declaration read:

His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

This statement, which became known as “The Balfour Declaration”, was cited by the Zionist leadership as having legitimized their aspirations, which had been reiterated by Lord Rothschild just a few months prior, on July 18, in a memorandum that expressed “the principle that Palestine should be re-constituted as the National Home for the Jewish People.” Any opinion the Arabs might have had about their homeland being so “re-constituted” was of no consideration.[33]

The purpose of the declaration was to secure Jewish support for the war effort. As Prime Minister Lloyd George noted, it was for “propaganda reasons”. The aforementioned 1937 British commission headed up by Lord William Peel explained that “it was believed that Jewish sympathy or the reverse would make a substantial difference one way or the other to the Allied cause. In particular Jewish sympathy would confirm the support of American Jewry . . . .” The Zionist leaders promised that, “if the Allies committed themselves to giving facilities for the establishment of a national home for the Jews in Palestine, they would do their best to rally Jewish sentiment and support throughout the world to the Allied cause.”[34]

“The fact that the Balfour Declaration was issued in 1917 in order to enlist Jewish support for the Allies and the fact that this support was forthcoming”, the Peel Commission further remarked, “are not sufficiently appreciated in Palestine.”[35]

The wording “national home for the Jewish people” was chosen because it was not politically feasible for the British government to “commit itself to the establishment of a Jewish State” in the place of Palestine; the best it could do was to facilitate immigration and deny self-determination to the people of Palestine—the only one of the formerly mandated territories whose independence was not recognized—until such time as the Jews had managed to establish a majority.[36]

The problem with this plan was that the Arabs recognized that the goal of the Zionist project “would ultimately tend to their political and economic subjection. The Arabs were aware that this prospect was definitely envisaged not only by the Zionists of the ‘extremist’ kind, . . . but also by more responsible representatives of Zionism, such as Dr. Eder, the acting chairman of the Zionist Commission . . . .”[37]

The Peel Commission further acknowledged that “the forcible conversion of Palestine into a Jewish State against the will of the Arabs . . . would mean that national self-determination had been withheld when the Arabs were a majority in Palestine and only conceded when the Jews were a majority. It would mean that the Arabs had been denied the opportunity of standing by themselves: that they had, in fact, after an interval of conflict, been bartered about from Turkish sovereignty to Jewish sovereignty.”[38]

In an effort to allay Arab apprehension and garner their support, as well, for the war effort, Western governments promised the people of the region their independence. In January 1918, President Woodrow Wilson outlined his “fourteen points”, promising respect for the right to self-determination and independence for the people living under Turkish rule: “The Turkish portions of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development.”[39]

On November 7, 1918, the British and French governments issued a joint declaration stating that “The object aimed at by France and Great Britain in prosecuting in the East the war let loose by German ambition is the complete and definite emancipation of the peoples so long oppressed by the Turks, and the establishment of National Governments and administrations deriving their authority from the initiative and free choice of the indigenous populations.”[40]

The British were not incognizant of the self-contradictory nature of its promises. In a memorandum to British Foreign Secretary George Curzon on August 11, 1919, Lord Balfour acknowledged the “flagrant” contradictions of British policy, but dismissed it as a matter of no concern:

For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country . . . . The four great powers are committed to Zionism and Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, and far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.

No declaration had been made by the British with regard to the inhabitants of Palestine, Balfour added, that “they have not always intended to violate”.[41]

As the Peel Commission later noted, “It was never doubted that the experiment”—meaning the Zionist project—“would have to be controlled by one of the Great Powers; and to that end it was agreed . . . that Palestine should have its place in the new Mandate System . . . .”[42]

The League of Nations’ Mandate for Palestine was intended to give the color of law to Britain’s occupation and the policies enacted under its administration. It was not only favorable toward their goals, but was effectively written by the Zionists themselves. As the Peel Commission pointed out:

On the 3rd February the Zionist Organisation presented a draft resolution embodying its scheme for the execution of the Balfour Declaration. On the 27th of February its leaders appeared before the Supreme Council and explained the scheme. A more detailed plan, dated the 28th of March, was drafted by Mr. Felix Frankfurter, an eminent American Zionist. From these and other documents and records it is clear that the Zionist project had already in those early days assumed something like the shape of the Mandate as we know it.[43]

Not surprisingly, given the Zionists’ role in drafting the Mandate, it included the terms of the Balfour Declaration, charging the British with enacting policies to “secure the establishment of the Jewish national home”—including the facilitation of Jewish immigration—and requiring the British administration to consult and cooperate with the Jewish Agency toward that end.

It contained no provisions assuring the Arab majority that they would have a say in the administration of their homeland by the foreign occupying power and its European colonialist partners.[44]

The Expropriation of the Land

As Theodor Herzl had envisioned, the Mandate facilitated the process of expropriation and removal of the poor Arab peasants by the Zionists, including by denying them employment. The Constitution of the Jewish Agency for Palestine signed in Zurich on August 14, 1920, stated:

Land is to be acquired as Jewish property and . . . the title to the lands acquired is to be taken in the name of the Jewish National Fund [JNF], to the end that the same shall be held as the inalienable property of the Jewish people. . . . The Agency shall promote agricultural colonization based on Jewish labour, and in all works or undertakings carried out or furthered by the Agency, it shall be deemed to be a matter of principle that Jewish labour shall be employed . . . .[45]

A 1930 report by Sir John Hope Simpson for the British government on immigration, land settlement, and development noted that, “Actually the result of the purchase of land in Palestine by the Jewish National Fund has been that the land has been extraterritorialised. It ceases to be land from which the Arab can gain any advantage either now or at any time in the future. Not only can he never hope to lease or to cultivate it, but, by the stringent provisions of the lease of the Jewish National Fund, he is deprived for ever from employment on that land.”[46]

The prejudice underlying the JNF’s policy blinded the Zionist leadership to the harm it also caused to Jewish landowners. The 1921 British Haycraft Commission report cited an example:

[T]he Zionist Commission put strong pressure upon a large Jewish landowner of Richon-le-Zion to employ Jewish labour in place of the Arabs who had been employed on his farm since he was a boy. The farmer, we were told, yielded to this pressure with reluctance, firstly, because the substitution of Jewish for Arab labour would alienate the Arabs, secondly, because the pay demanded by the Jewish labourers, and the short hours during which they would consent to work, would make it impossible for him to run his farm at a profit.[47]

Relations between Jews and Arabs in the JNF colonies were contrasted by relations in the settlements of the Palestine Jewish Colonisation Association (PICA) funded by Baron Edmond de Rothschild. The 1930 Hope Simpson Report observed:

In so far as the past policy of the P.I.C.A. is concerned, there can be no doubt that the Arab has profited largely by the installation of the colonies. Relations between the colonists and their Arab neighbours were excellent. In many cases, when land was bought by the P.I.C.A. for settlement, they combined with the development of the land for their own settlers similar development for the Arabs who previously occupied the land. All the cases which are now quoted by the Jewish authorities to establish the advantageous effect of Jewish colonization on the Arabs of the neighbourhood, and which have been brought to notice forcibly and frequently during the course of this enquiry, are cases relating to colonies established by the P.I.C.A., before the KerenHeyesod [JNF] came into existence. In fact, the policy of the P.I.C.A. was one of great friendship for the Arab. Not only did they develop the Arab lands simultaneously with their own, when founding their colonies, but they employed the Arab to tend their plantations, cultivate their fields, to pluck their grapes and their oranges. As a general rule the P.I.C.A. colonization was of unquestionable benefit to the Arabs of the vicinity.

It is also very noticeable, in travelling through the P.I.C.A. villages, to see the friendliness of the relations which exist between Jew and Arab. It is quite a common sight to see an Arab sitting in the verandah of a Jewish house. The position is entirely different in the Zionist colonies.[48]

Had the Jewish settlement in Palestine proceeded along the lines of the PICA colonies, history would undoubtedly have been very different. Alas, it was the policies of the JNF that came to characterize the nature of the colonization project. As the Hope Simpson Report noted:

At the moment this policy is confined to the Zionist colonies, but the General Federation of Jewish Labour is using every effort to ensure that it shall be extended to the colonies of the P.I.C.A., and this with some considerable success. . . . It will be a matter of great regret if the friendly spirt which characterized the relations between the Jewish employer in the P.I.C.A. villages and his Arab employees . . . were to disappear. Unless there is some change of spirit in the policy of the Zionist Organisation it seems inevitable that the General Federation of Jewish Labour, which dominates that policy, will succeed in extending its principles to all the Jewish colonies in Palestine. . . . The Arab population already regards the transfer of lands to Zionist hands with dismay and alarm. These cannot be dismissed as baseless in the light of the Zionist policy . . . .[49]

Another aspect of the Zionists’ land purchases was how it disenfranchised Arab inhabitants who had theretofore been living on and working the land. This was achieved by exploiting feudalistic Ottoman land laws. Under the Ottoman Land Code of 1858, the state effectively claimed ownership of the land and individuals were regarded as tenants. Subsequently, the law was amended so individuals could register for a title-deed to the land, but landholders often saw no need to do so unless they were interested in selling. Moreover, there were incentives not to register, including the desire to avoid granting legitimacy to the Ottoman government, to avoid paying registration fees and taxes, and to evade possible military conscription. Additionally, land lived on and cultivated by one individual or family was often registered in the name of another, such as local government magnates who registered large plots or even entire villages in their own names.[50]The British Shaw Commission report of 1929 described another common means by which the rightful owners of the land were legally disenfranchised:

Under the Turkish regime, especially in the latter half of the eighteenth century, persons of the peasant classes in some parts of the Ottoman Empire, including the territory now known as Palestine, found that by admitting the over-lordship of the Sultan or of some member of the Turkish aristocracy, they could obtain protection against extortion and other material benefits which counterbalanced the tribune demanded by their over-lord as a return for his protection. Accordingly many peasant cultivators at that time either willingly entered into an arrangement of this character or, finding that it was imposed upon them, submitted to it. By these means persons of importance and position in the Ottoman Empire acquired the legal title to large tracts of land which for generations and in some cases for centuries had been in the undisturbed and undisputed occupation of peasants who . . . had undoubtedly a strong moral claim to be allowed to continue in occupation of those lands.[51]

Much of the land acquired by the JNF was purchased from absentee landlords, with extreme prejudice toward the poor Arab inhabitants who by rights were its legitimate owners.[52] According to the Shaw Commission, no more than 10 percent of purchased land was acquired from peasants, the rest having been “acquired from the owners of large estates most of whom live outside Palestine”.[53] In the Vale of Esdraelon, for instance, “one of the most fertile parts of Palestine”, Jews purchased 200,000 dunams (more than 49,000 acres) from a wealthy family of Christian Arabs from Beirut (the Sursock family). Included in the purchase were 22 villages, “the tenants of which, with the exception of a single village, were displaced: 1,746 families or 8,730 people.”[54] As another example, in the Wadi el Hawareth area, the JNF purchased 30,826 dunams (more than 7,600 acres) and evicted a large proportion its 1,200 Arab inhabitants.[55]

Resolution 181 and the Early Phases of the 1948 War

Despite their best efforts, by the end of the Mandate, the Jewish settlers had managed to acquire only about 7 percent of the land in Palestine. Arabs owned more land than Jews in every single district, including Jaffa, which included the largest Jewish population center, Tel Aviv. According to the UNSCOP report, “The Arab population, despite the strenuous efforts of Jews to acquire land in Palestine, at present remains in possession of approximately 85 percent of the land.” A subcommittee report further observed that “The bulk of the land in the Arab State, as well as in the proposed Jewish State, is owned and possessed by Arabs” (emphasis added). Furthermore, the Jewish population in the area of their proposed state was 498,000, while the number of Arabs was 407,000 plus an estimated 105,000 Bedouins. “In other words,” the subcommittee report noted, “at the outset, the Arabs will have a majority in the proposed Jewish State.”

UNSCOP nevertheless proposed that the Arab state be constituted from about 44 percent of the whole of Palestine, while the Jews would be awarded about 55 percent for their state, including the best agricultural lands. The committee was not incognizant of how this plan prejudiced the rights of the majority Arab population. In fact, in keeping with the prejudice inherent in the Mandate, the UNSCOP report explicitly rejected the right of the Arab Palestinians to self-determination. The “principle of self-determination” was “not applied to Palestine,” the report stated, “obviously because of the intention to make possible the creation of the Jewish National Home there. Actually, it may well be said that the Jewish National Home and the sui generis Mandate for Palestine run counter to that principle.”[56]

Given the proper historical context, we can now return to Benny Morris’s argument that “the Palestinians were the ones who started the war when they rejected the UN compromise plan and embarked on hostile acts”. This argument assumes that the Arabs’ rejection of the plan was somehow unreasonable. It was not.

Morris’s argument also assumes that Resolution 181 somehow lent legitimacy to the Zionists’ goal of establishing a “Jewish state” in Palestine within the area proposed under UNSCOP’s plan. It did not. While it is a popular myth that the UN created Israel, the partition plan was actually never implemented. Resolution 181 merely recommended that Palestine be partitioned and referred the matter to the Security Council, where it died. Needless to say, neither the General Assembly nor the Security Council had any authority to partition Palestine against the will of the majority of its inhabitants.

Although Resolution 181 was cited in Israel’s founding document as having granted legitimacy to the establishment of the “Jewish state”, in truth, the resolution neither partitioned Palestine nor conferred any legal authority to the Zionists for their unilateral declaration of the existence of the state of Israel on May 14, 1948.[57]

When Morris says that the Arabs states had declared their intent “to attack the Jewish state when the British left”, what he really means, therefore, is that they declared their intent to take up arms to prevent the Zionists from unilaterally declaring for themselves sovereignty over lands they had no rights to and politically disenfranchising the majority population of Palestine.

Morris employs this same rhetorical device—a mainstay of Zionist propaganda—in his book 1948 to suggest that it was the Arabs who were the aggressors, while the Jews were simply defending themselves. For example, he emphasizes that “most of the fighting between November 1947 and mid-May 1948 occurred in the areas earmarked for Jewish statehood”—thus implying that most of the fighting occurred on land rightfully belonging to the Jews. However, the fact that most of the violence occurred within this area is completely irrelevant and tells us nothing about which side was guilty of aggression. After all, Arabs owned more land than Jews and much of this fighting took place in Arab villages and towns located within that same “earmarked” territory.

It is largely on the basis of his assumption that the land proposed for the Jewish state under the partition plan was indeed rightfully the Jews’ that he can sustain his narrative that, “From the end of November 1947 until the end of March 1948, the Arabs held the initiative and the Haganah was on the strategic defensive.”[58] “Going into the civil war, Haganah policy was purely defensive”, Morris repeats—although he grants that “the mainstream Zionist leaders, from the first, began to think of expanding the Jewish state beyond the 29 November partition resolution borders”; and its “defensive policy” during the early months of the war “was dictated in part by a lack of means” as it “was not yet ready for large-scale offensive operations”.[59] But the Arabs initiated the violence, in Morris’s account, and the Haganah acted in self-defense while “occasionally retaliating against Arab traffic, villages, and urban neighborhoods.”[60]

Ilan Pappé sheds some additional light on how the Haganah’s “defensive” operations were undertaken:

The first step was a well-orchestrated campaign of threats. Special units of the Hagana would enter villages looking for ‘infiltrators’ (read ‘Arab volunteers’) and distribute leaflets warning the local people against cooperating with the Arab Liberation Army. Any resistance to such an incursion usually ended with the Jewish troops firing at random and killing several villagers. The Hagana called these incursions ‘violent reconnaissance’ (hasiyur ha-alim). . . . In essence the idea was to enter a defenceless village close to midnight, stay there for a few hours, shoot at anyone who dared leave his or her house, and then depart.[61]

For example, on December 18, 1947, the Haganah attacked the village of Khisas at night, randomly blowing up houses with the occupants sleeping inside, killing fifteen, including five children. With a New York Times reporter having closely followed the events, Ben-Gurion issued a public apology and claimed the attack had been unauthorized; but “a few months later, in April, he included it in a list of successful operations.”[62]

“Much of the fighting in the first months of the war”, writes Morris, “took place in and on the edges of the main towns—Jerusalem, Tel Aviv–Jaffa, and Haifa. Most of the violence was initiated by the Arabs. Arab snipers continuously fired at Jewish houses, pedestrians, and traffic and planted bombs and mines along urban and rural paths and roads.” He describes “several days of sniping and Haganah responses in kind”—a typical example of how he characterizes the Haganah’s violence as occurring in self-defense or as retaliation for earlier Arab attacks he identifies as having initiated any given round of fighting.[63]

Pappé again offers some additional illumination that once again calls into question Morris’s assertion that it was the Arabs who were mostly responsible for initiating the violence. With respect to Haifa, Pappé writes:

From the morning after the UN Partition Resolution was adopted, the 75,000 Palestinians in the city were subjected to a campaign of terror jointly instigated by the Irgun and the Hagana. As they had only arrived in recent decades, the Jewish settlers had built their houses higher up the mountain. Thus, they lived topographically above the Arab neighbourhoods and could easily shell and snipe at them. They had started doing this frequently since early December. They used other methods of intimidation as well: the Jewish troops rolled barrels full of explosives, and huge steel balls, down into the Arab residential areas, and poured oil mixed with fuel down the roads, which they then ignited. The moment panic-stricken Palestinian residents came running out of their homes to try to extinguish these rivers of fire, they were sprayed with machine-gun fire. In areas where the two communities still interacted, the Hagana brought cars to Palestinian garages to be repaired, loaded with explosives and detonating devices, and so wreaked death and chaos. A special unit of the Hagana, Hashahar (‘Dawn’), made up of mistarvim—literally Hebrew for ‘becoming Arab’, that is Jews who disguised themselves as Palestinians—was behind this kind of assault. The mastermind of these operations was someone called Dani Agmon, who headed the ‘Dawn’ units. On its website, the official historian of the Palmach puts it as follows: ‘The Palestinians [in Haifa] were from December onwards under siege and intimidation.’ But worse was to come.[64]

Plan D

Morris’s debate with his critics centers largely around “Plan D”, for “Dalet”, the fourth letter of the Hebrew alphabet. In contrast to what he describes as the Zionists’ “defensive” stage of the war, Plan D marked, by his own account, the beginning of their “war of conquest”.[65]

Morris is correct that Plan D did not explicitly call for “expelling as many Arabs as possible from the territory of the future Jewish state”, as Blatman suggests. But neither did it order that “neutral or friendly villages should be left untouched”, as Morris contends.

Under Plan D, brigade commanders were to use their own discretion in mounting operations against “enemy population centers”—meaning Arab towns and villages—by choosing between the following options:

—Destruction of villages (setting fire to, blowing up, and planting mines in the debris), especially those population centers which are difficult to control continuously.

—Mounting combing and control operations according to the following guidelines: encirclement of the village and conducting a search inside it. In the event of resistance, the armed force must be wiped out and the population must be expelled outside the borders of the state.[66]

Thus, while Plan D allowed for Arab inhabitants to remain as long as they did not resist the takeover of their villages by the Zionist forces, it did not order Haganah commanders to permit them to stay under such circumstances—as Morris falsely suggests in the second of his responses in Haaretz.

Nor is Morris incognizant of the critical distinction. In 1948, he explicitly notes that “brigade commanders were given the option” of destroying Arab villages (emphasis added)—which would obviously necessitate expelling their inhabitants—regardless of whether any of the villagers offered any resistance. “The commanders were given discretion whether to evict the inhabitants of villages and urban neighborhoods sitting on vital access roads”, Morris writes (emphasis added). “The plan gave the brigades carte blanche to conquer the Arab villages and, in effect, to decide on each village’s fate—destruction and expulsion or occupation. The plan explicitly called for the destruction of resisting Arab villages and the expulsion of their inhabitant” (emphasis added).[67]

As Ilan Pappé expounds, “Villages were to be expelled in their entirety either because they were located in strategic spots or because they were expected to put up some sort of resistance. These orders were issued when it was clear that occupation would always provoke some resistance and that therefore no village would be immune, either because of its location or because it would not allow itself to be occupied.”[68]By these means, by the time the war ended, the Zionist forces had expelled the inhabitants of and destroyed 531 villages and emptied eleven urban neighborhoods of their Arab residents.[69]

Pappé further notes how the facts on the ground at the time challenge Morris’s characterization of the Zionist’s operations as having been “defensive” prior to the implementation of Plan D:

The reality of the situation could not have been more different: the overall military, political and economic balance between the two communities was such that not only were the majority of Jews in no danger at all, but in addition, between the beginning of December 1947 and the end of March 1948, their army had been able to complete the first stage of the cleansing of Palestine, even before the master plan had been put into effect. If there were a turning point in April, it was the shift from sporadic attacks and counter-attacks on the Palestinian civilian population towards the systematic mega-operation of ethnic cleansing that now followed.[70]

In Haaretz, Morris adds that in the larger urban areas with mixed populations, under Plan D, the orders were for the Arabs “to be transferred to the Arab centers of those cities, like Haifa, not expelled from the country.” Morris also writes that the Zionists “left Arabs in place in Haifa”, and he cites it as an example of a place where Arabs “were ordered or encouraged by their leaders to flee”—as opposed to them being expelled by the Zionist forces.

But the details Morris provides in 1948 of what happened in Haifa tell an altogether different story.

By the end of March 1948, most of the wealthy and middle-class families had fled Haifa. Far from ordering this evacuation, the Arab leadership had blasted those who fled as “cowards” and tried to prevent them from leaving.[71] Among the reasons for the flight were terrorist attacks by the Irgun that had sowed panic in Haifa and other cities. On the morning of December 30, 1947, for example, the Irgun threw “three bombs from a passing van into a crowd of casual Arab laborers at a bus stop outside the Haifa Oil Refinery, killing eleven and wounding dozens.”[72] (Ilan Pappé notes that “Throwing bombs into Arab crowds was the specialty of the Irgun, who had already done so before 1947.”[73] And as Morris points out, Arab militias took note of the methods of the Irgun and Lehi and eventually started copying them: “The Arabs had noted the devastating effects of a few well-placed Jewish bombs in Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Haifa . . . .”[74]) Arab laborers inside the plant responded by turning against their Jewish coworkers, killing thirty-nine and wounding fifty (several Arab employees did try to protect their Jewish co-workers).[75]

The Haganah retaliated by targeting a nearby village that was home to many of the refinery workers. The orders were to spare the women and children, but to kill the men. “The raiders moved from house to house, pulling out men and executing them. Sometimes they threw grenades into houses and sprayed the interiors with automatic fire. There were several dozen dead, including some women and children.” Ben-Gurion defended the attack by saying it was “impossible” to “discriminate” under the circumstances. “We’re at war. . . . There is an injustice in this, but otherwise we will not be able to hold out.”[76]

Marking “the start of the implementation of Plan D”, writes Morris, was Operation Nahshon in April 1948.[77] By this time, tens of thousands of Haifa’s seventy thousand Arabs had already fled.[78] The Haganah had been planning an operation in Haifa since mid-month, and when the British withdrew their troops from positions between Arab and Jewish neighborhoods on April 21, it provided the Haganah with the opportunity to put it into effect.[79] The Haganah fired mortars indiscriminately into the lower city, and by noon “smoke rose above gutted buildings and mangled bodies littered the streets and alleyways.” The mortar and machine gun fire “precipitated mass flight toward the British-held port area”, where Arab civilians trampled each other to get to boats, many of which were capsized in the mad rush.[80]

The British high commissioner, Sir Alan Cunningham, described the Haganah’s tactics: “Recent Jewish military successes (if indeed operations based on the mortaring of terrified women and children can be classed as such) have aroused extravagant reactions in the Jewish press and among the Jews themselves a spirit of arrogance which blinds them to future difficulties. . . . Jewish broadcasts both in content and in manner of delivery, are remarkably like those of Nazi Germany.”[81]

It was under these circumstances that the local Arab leaders sought to negotiate a truce, and in a British-mediated meeting in the afternoon on April 22, the Jewish forces proposed a surrender agreement that “assured the Arab population a future ‘as equal and free citizens of Haifa.’”[82] But the Arab notables, after taking some time to consult before reconvening, informed that they were in no position to sign the truce since they had no control over the Arab combatants in Haifa and that the population was intent on evacuating. Jewish and British officials at the meeting tried to persuade them to sign the agreement, to no avail. In the days that followed, nearly all of Haifa’s remaining inhabitants fled, with only about 5,000 remaining.

While in his Haaretz article, Morris attributed this flight solely to orders from the Arab leadership to leave the city, in 1948, he notes that other factors included psychological trauma from the violence—especially the Haganah’s mortaring of the lower city—and despair at the thought of living now as a minority under a people who had just inflicted that collective punishment upon them. Furthermore, “The Jewish authorities almost immediately grasped that a city without a large (and actively or potentially hostile) Arab minority would be better for the emergent Jewish state, militarily and politically. Moreover, in the days after 22 April, Haganah units systematically swept the conquered neighborhoods for arms and irregulars; they often handled the population roughly; families were evicted temporarily from their homes; young males were arrested, some beaten. The Haganah troops broke into Arab shops and storage facilities and confiscated cars and food stocks. Looting was rife.”[83]

This, then, is the situation Morris is describing when he disingenuously writes in Haaretz that the Zionist forces “left Arabs in place in Haifa” and that Arabs fled Haifa because they were “ordered or encouraged by their leaders”.

We can also compare Morris’s account of how the village of Lifta came to be emptied of its Arab inhabitants with Ilan Pappé’s. 1984 contains only one mention of Lifta, a single sentence in which Morris characterizes it as another example of how Arabs fled upon the orders of their leadership: “For example, already on 3–4 December 1947 the inhabitants of Lifta, a village on the western edge of Jerusalem, were ordered to send away their women and children (partly in order to make room for incoming militiamen).”[84]

Pappé tells a remarkably different story, describing Lifta, with its population of 2,500, as “one of the very first to be ethnically cleansed”:

Social life in Lifta revolved around a small shipping centre, which included a club and two coffee houses. It attracted Jerusalemites as well, as no doubt it would today were it still there. One of the coffee houses was the target of the Hagana when it attacked on 28 December 1947. Armed with machine guns the Jews sprayed the coffee house, while members of the Stern Gang stopped a bus nearby and began firing into it randomly. This was the first Stern Gang operation in rural Palestine; prior to the attack, the gang had issued pamphlets to its activists: ‘Destroy Arab neighbourhoods and punish Arab villages.’

The involvement of the Stern Gang in the attack on Lifta may have been outside the overall scheme of the Hagana in Jerusalem, according to the Consultancy [i.e., Ben-Gurion and his close advisors], but once it had occurred it was incorporated into the plan. In a pattern that would repeat itself, creating faits accomplis became part of the overall strategy. The Hagana High Command at first condemned the Stern Gang attack at the end of December, but when they realized that the assault had caused the villagers to flee, they ordered another operation against the same village on 11 January in order to complete the expulsion. The Hagana blew up most of the houses in the village and drove out all the people who were still there.[85]

The lesson learned was also applied in Jerusalem. On February 7, 1948, Ben-Gurion went to see Lifta for himself and that evening reported to a council of the Mapai party in Jerusalem:

When I come now to Jerusalem, I feel I am in a Jewish (Ivrit) city. This is a feeling I only had in Tel-Aviv or in an agricultural farm. It is true that not all of Jerusalem is Jewish, but it has in it already a huge Jewish bloc: when you enter the city through Lifta and Romema, through Mahaneh Yehuda, King George Street and Mea Shearim—there are no Arabs. One hundred percent Jews. Ever since Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans—the city was not as Jewish as it is now. In many Arab neighbourhoods in the West you do not see even one Arab. I do not suppose it will change. And what happened in Jerusalem and in Haifa—can happen in large parts of the country. If we persist it is quite possible that in the next six or eight months there will be considerable changes in the country, very considerable, and to our advantage. There will certainly be considerable changes in the demographic composition of the country.[86]

Note that all of this happened well before explicit orders were given to destroy villages and expel their inhabitants if anyone resisted occupation by the Zionist forces. From mid-March onward, in Morris’s own words, “In line with Plan D, Arab villages were henceforward to be leveled to prevent their reinvestment by Arab forces; the implication was that their inhabitants were to be expelled and prevented from returning.”[87] The Haganah “embarked on a campaign of clearing areas of Arab inhabitants and militia forces and conquering and leveling villages”.[88] Plan D implemented a “new policy, of permanently occupying and/or razing villages and of clearing whole areas of Arabs”.[89]

Morris’s contention that what happened wasn’t ethnic cleansing because most Palestinians fled, as opposed to being expelled by the Zionist forces, becomes a moot distinction in light of how, for example, a massacre that occurred in the Arab village of Deir Yassin in April was “amplified through radio broadcasts . . . to encourage a mass Arab exodus from the Jewish state-to-be.”[90]

In the Galilee, “the Arab inhabitants of the towns of Beit Shean (Beisan) and Safad had to be ‘harassed’ into flight”, according to a planned series of operations conceived in April (“in line with Plan D”, Morris notes). In charge of these operations was the commander of the Palmach, Yigal Allon.[91] On May 1, two villages north of Safad were captured. Several dozen male prisoners were executed, and the Palmach “proceeded to blow up the two villages as Safad’s Arabs looked on. The bulk of the Third Battalion then moved into the town’s Jewish Quarter and mortared the Arab quarters”, prompting many of Safad’s Arab inhabitants to flee.[92]

After five days, the Arabs sought a truce, which Allon rejected. Even some of the local Jews “sought to negotiate a surrender and demanded that the Haganah leave town. But the Haganah commanders were unbending” and continued pounding Safad with mortars and its arsenal of 3-inch Davidka munitions. The first of the Davidka bombs, according to Arab sources cited by a Haganah intelligence document, killed 13 Arabs, mostly children, which triggered a panic and further flight. This, of course, was precisely what was “intended by the Palmah commanders when unleashing the mortars against the Arab neighborhoods”—which, “literally overnight, turned into a ‘ghost town’”. In the weeks that followed, “the few remaining Arabs, most of them old and infirm or Christians, were expelled to Lebanon or transferred to Haifa.”[93]

Yigal Allon summed up the purpose of the Palmach’s operations: “We regarded it as imperative to cleanse the interior of the Galilee and create Jewish territorial continuity in the whole of Upper Galilee.” He boasted of how he devised a plan to rid the Galilee of tens of thousands of Arabs without having to actually use force to drive them out. His strategy, which “worked wonderfully”, was to plant rumors that additional reinforcements had arrived “and were about to clean out the villages of the Hula [Valley]”. Local Jewish leaders with ties to the area’s villages were tasked with advising their Arab neighbors, “as friends, to flee while they could. And the rumor spread throughout the Hula that the time had come to flee. The flight encompassed tens of thousands.”[94]

Morris adds that, “To reinforce this ‘whispering,’ or psychological warfare, campaign, Allon’s men distributed fliers, advising those who wished to avoid harm to leave ‘with their women and children.’”[95]

Morris’s denial that these events he describes constituted ethnic cleansing seems difficult to reconcile with Allon’s statement that the goal of the Palmach’s operations in the Galilee was “to cleanse” the area of its Arab inhabitants. In his 2004 interview with Ari Shavit, Morris also noted with respect to the use of the verb “cleanse” to describe what happened throughout Palestine, “I know it doesn’t sound nice but that’s the term they used at the time. I adopted it from all the 1948 documents in which I am immersed.”

Indeed, Morris himself used the term repeatedly in his discussion with Shavit, in which Morris expressed his view that this “cleansing” of Palestine was morally justified:

Ben-Gurion was right. If he had not done what he did, a state would not have come into being. That has to be clear. It is impossible to evade it. Without uprooting of the Palestinians, a Jewish state would not have arisen here. . . .

There is no justification for acts of rape. There is no justification for acts of massacre. Those are war crimes. But in certain conditions, expulsion is not a war crime. I don’t think that the expulsions of 1948 were war crimes. You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs. You have to dirty your hands. . . .

There are circumstances in history that justify ethnic cleansing. I know that this term is completely negative in the discourse of the 21st century, but when the choice is between ethnic cleansing and genocide—the annihilation of your people—I prefer ethnic cleansing. . . .

That was the situation. That is what Zionism faced. A Jewish state would not have come into being without the uprooting of 700,000 Palestinians. Therefore it was necessary to uproot them. There was no choice but to expel that population. . . .

I feel sympathy for the Palestinian people, which truly underwent a hard tragedy. I feel sympathy for the refugees themselves. But if the desire to establish a Jewish state here is legitimate, there was no other choice. . . .

But I do not identify with Ben-Gurion. I think he made a serious historical mistake in 1948. Even though he understood the demographic issue and the need to establish a Jewish state without a large Arab minority, he got cold feet during the war. In the end, he faltered. . . .

If he was already engaged in expulsion, maybe he should have done a complete job. . . .

If the end of the story turns out to be a gloomy one for the Jews, it will be because Ben-Gurion did not complete the transfer in 1948. Because he left a large and volatile demographic reserve in the West Bank and Gaza and within Israel itself. . . .

The non-completion of the transfer was a mistake.[96]

Morris’s recent denial that what occurred was ethnic cleansing is also difficult to reconcile with these earlier comments of his. Indeed, that would seem quite impossible, which is presumably why Morris made no attempt to do so after Steven Klein, in his contribution to the debate, had pointed out these words of Morris’s.

The Fallacies of Morris’s Arguments

Now that the proper historical context has been established, let’s return to Morris’s arguments and address each in turn.

Morris denies that the Jewish leadership “carried out a policy of expelling the local Arabs”. This denial is untenable. Logically, the goal of establishing a demographically “Jewish state” would require the “compulsory transfer”—to borrow Ben-Gurion’s phrase for it, in turn borrowed from the Peel Commission—of a large number of Arabs. Ben-Gurion and other Zionist leaders had explicitly stated their desire to effect this “transfer”, and once war broke out there was a clear tacit understanding between the political leadership and the military commanders toward that end. As Morris himself has pointed out, there was an “atmosphere of transfer”, and commanders who carried out such expulsions were not punished.