Britain’s “mandate” over Palestine from 1920-48 left an apparatus of repression which Israel inherited and still uses today in its ferocious war on Palestinians, writes A. Bustos.

Members of the U.K. Royal Commission during the Palestine “disturbances” of 1936. (Library of Congress)

Israel’s present use of collective punishment against Palestinians owes much of its origins to British rule in Palestine.

So too do the aerial bombardments, military raids, use of Palestinian civilians as human shields and the infrastructure of military law deployed against an occupied, overwhelmingly civilian population.

Britain ruled Palestine during its “mandate” between 1920-48, and its repressive infrastructure came into full force during the 1936-39 Great Arab Revolt.

In 1936, Palestine erupted into a national uprising following two decades of peaceful resistance against British rule and several failed uprisings over the 1920s, as the political and economic situation became dire for the Arab majority.

The uprising called for an end to British support for Zionist colonisation and a guarantee of Palestinian self-determination. Britain, however, saw it as a threat to its rule and responded with brutal repression.

By the end of the revolt, 10 percent of the adult male Arab population were either killed, wounded, imprisoned or exiled by the British.

This brought the revolt to an end, devastated Palestinian society and left it defenceless against Zionist militia groups during the 1948 Nakba (catastrophe). Then, over two-thirds of the Palestinian people were ethnically cleansed from their country to establish the state of Israel.

Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi has argued that the armed suppression of Arab resistance during the revolt was among the most valuable services Britain provided to the Zionist movement.

Martial Law

Palestine resistance fighters against the British mandate, 1936. (PLO Collection, Institute for Palestine Studies, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

To crush the revolt, Britain brought Palestine under martial law, building on counterinsurgency tactics it had refined in other colonies like Ireland and India.

As historian Matthew Hughes explains, in response to the 1936 uprising, British authorities renewed local laws enacted during the 1920s, referring to them as “emergency laws”, to impose collective punishment against Palestinians.

This allowed the mandate government to impose curfews, censor written materials, occupy buildings, as well as arrest, imprison and deport individuals without trial while suspending the right to counsel, policies Israel still enforces against Palestinians today.

Far from distinguishing between armed rebels and civilians, Britain enforced collective punishment against the entire population. Mining the declassified files, David Cronin describes how “Britain’s elite decided early on that Palestinians should be targeted en masse”.

By 1937, Palestine was under effective military rule. During the mandate period, Britain had put in place a legal system which was designed to prevent Palestinian political organising while also giving itself broad powers.

Camps & Prisons

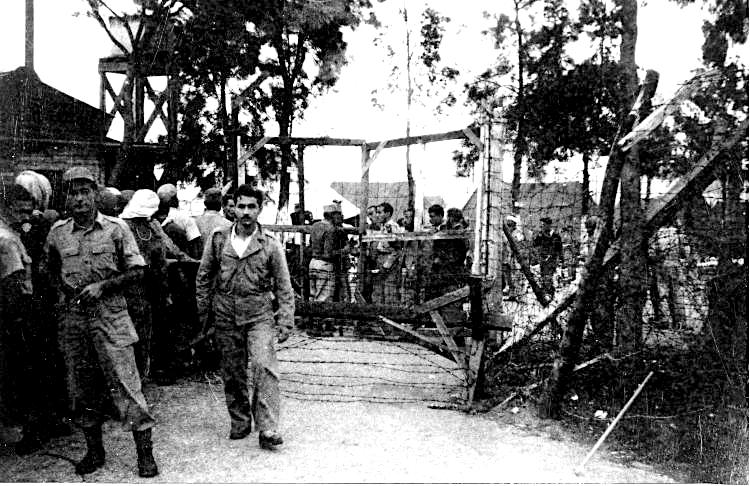

Israeli prison camp at Sarafand, November 1948. (Palmach archive Yiftach 1st Battalion D company Volume 2 album, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

British military rule turned large parts of the country into prisons. Military law made it possible to hand out swift sentences, meaning large-scale detentions of peasants and urban workers.

Detainees were held, often without trial, in extremely overcrowded camps with inadequate sanitation. In May 1939, answering a parliamentary question, colonial secretary Malcolm MacDonald confirmed that there were 13 detention camps in Palestine housing 4,816 people.

This included several concentration camps (as Britain itself referred to them) like Sarafand al-Amar, located at the largest military base in Palestine, which held thousands of prisoners.

Other camps included Nur Shams, near Tulkarem, and Acre prison on the Mediterranean coast which also hosted Palestine’s largest prison.

At one point the overcrowding was so bad it became necessary to release veteran detainees whenever new ones were arrested. In 1939 the number of detainees rose to over 9,000, 10 times the figure of two years previously.

According to Palestinian prisoner rights group, Addameer, at least six of the major Israeli prison and detention centres today were built during the mandate era. These include Kishon, Damon, Ramleh, Ashkelon, Megiddo and Al-Moscobiyeh (the Russian Compound) which are still used by Israel to imprison Palestinians.

Administrative Detention

Palestinian Youth Accord for Prisoners rally in Gaza support of Palestinian administrative detainees on a mass hunger strike, May 12, 2014. (Joe Catron, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

In November 2023, following a four-day humanitarian “pause” between Israel and Hamas, the Israeli government released hundreds of Palestinian prisoners. This shone a spotlight for Western audiences on the fact that thousands of Palestinians are regularly imprisoned today in Israeli jails.

What drew most attention was that so many of them, including children, were held under the policy ofadministrative detention, an unlawful process that allows Israel to hold detainees without charge or trial.

However, Israel appears to have inherited the practice from the British, who regularly detained thousands of Palestinians without trial. Following its establishment in 1948, Israel has practised detention without trial as a staple of military rule.

After the end of the revolt in 1939, Britain strengthened the powers of the mandate administration and in 1945 introduced the Defence (Emergency) Regulations. Ironically, this was in response to violence carried out by Zionist paramilitary groups at that time.

Israel incorporated these regulations and most other British mandate laws into the Israeli Law and Administration Ordinance of 1948. It used them against Palestinians inside Israel between 1948-66 and then extended them to Palestinians in the occupied territories of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967.

These laws would be used repeatedly in response to popular uprisings thereafter, this time against Israeli rule.

A 1989 report by Palestinian human rights organisation Al-Haq describes how Israeli commanders issued a proclamation in 1967 affirming that the Defence (Emergency) Regulations were to remain in force.

Even though they had been terminated by Britain at the end of its mandate, Israeli leaders kept and continued to use them against Palestinians.

In 2019, Human Rights Watch highlighted eight cases where Israeli authorities used military orders to “prosecute Palestinians in military courts for their peaceful expression or involvement in non-violent groups or demonstrations” using, among other measures, the Defence (Emergency) Regulations of 1945 inherited from Britain.

Charles Tegart’s Fence

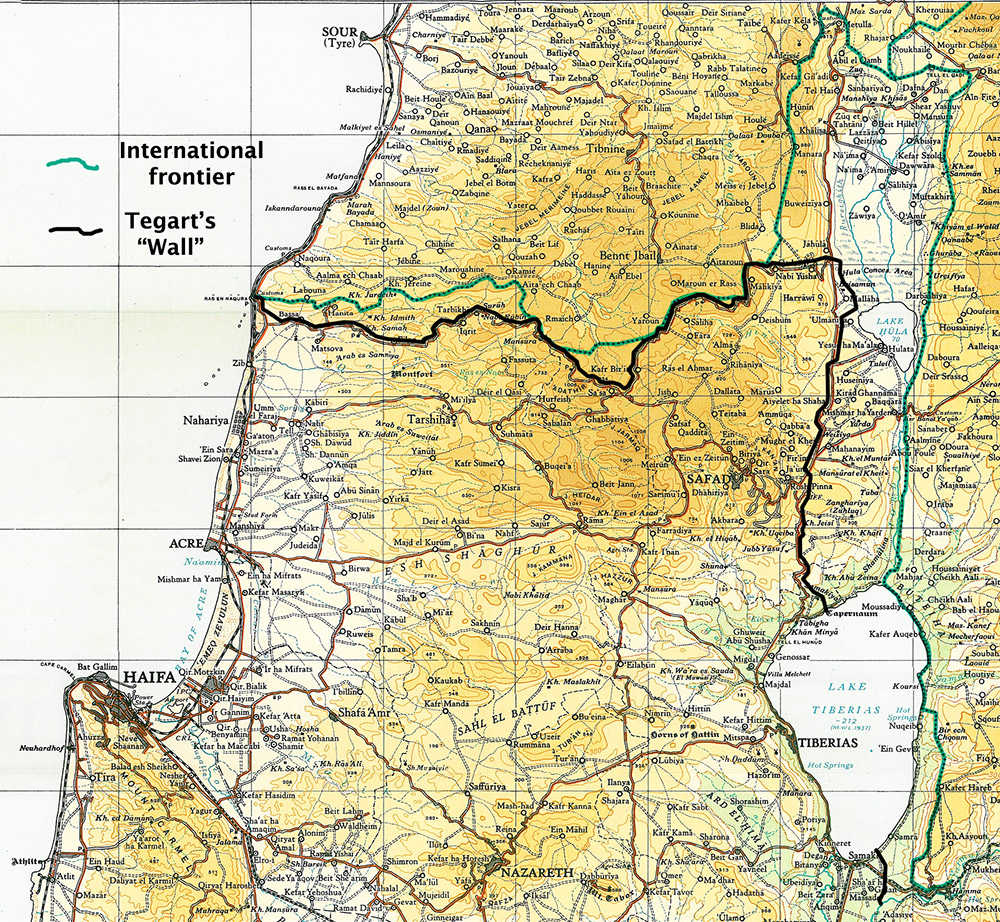

“Tegart’s Wall”, actually a barbed wire fence, Palestine 1938–1940. (Map prepared for the Survey of Palestine, 1944, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

To fight the 1930s revolt, Britain sent Sir Charles Tegart, who had previously headed the police force in colonial India, to Palestine where he built much of the infrastructure used to intern suspects. Tegart built so-called Arab Investigation Centres which were used as torture chambers.

He established a special centre in Jerusalem to train interrogators in torture where suspects underwent brutal questioning, involving humiliation, beatings, and physical mistreatment.

Colonial administrator Edward Keith-Roach recounted in his memoirs that the purpose of these centres was to train police officers “in the gentle art of ‘third degree’” for use on Arabs until they “spilled the beans”.

Israeli historian Tom Segev describes how Tegart “built dozens of police fortresses around the country and put up concrete guard posts, which the British called pillboxes, along the roads”.

Tegart Fort at Kibbutz Sasa, Upper Galile, Israel, 2010. (Ranbar, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Tegart’s best-known recommendation was that a huge fence be erected along Palestine’s northern border, which came to be known as “Tegart’s fence”.

To construct it, he enlisted the help of the Jewish Agency, the main organisation encouraging Jewish settlement to Palestine. The contract to build it was awarded to construction company Solel Bonehwhich was a project of the Histadrut, the leading Zionist trade union in Palestine and Israel’s national trade union today.

Solel Boneh also built the new police buildings, popularly known as the “Tegart Fortresses”. A 2012 BBC profile on Tegart describes how many of them are still used today.

Located mainly in the north of the country they are now situated near the Israeli border with Lebanon but instead of British troops, they are manned by Israeli soldiers.

Military Tactics

Britain used both ground troops and air power through the Royal Air Force against Palestinian rebels during 1936-39. Following the termination of the Munich Agreement made by Britain with Nazi Germany in 1938, Britain sent over 100,000 troops to Palestine, flooding the country with soldiers.

On May 7, 1936, the high commissioner for Palestine, Arthur Wauchope, sought “general covering approval” from the Colonial Office to impose collective punishment on cities and towns where acts of disobedience occurred.

He promptly received the go-ahead and chose Nazareth, Safed and Bisan to be penalised.

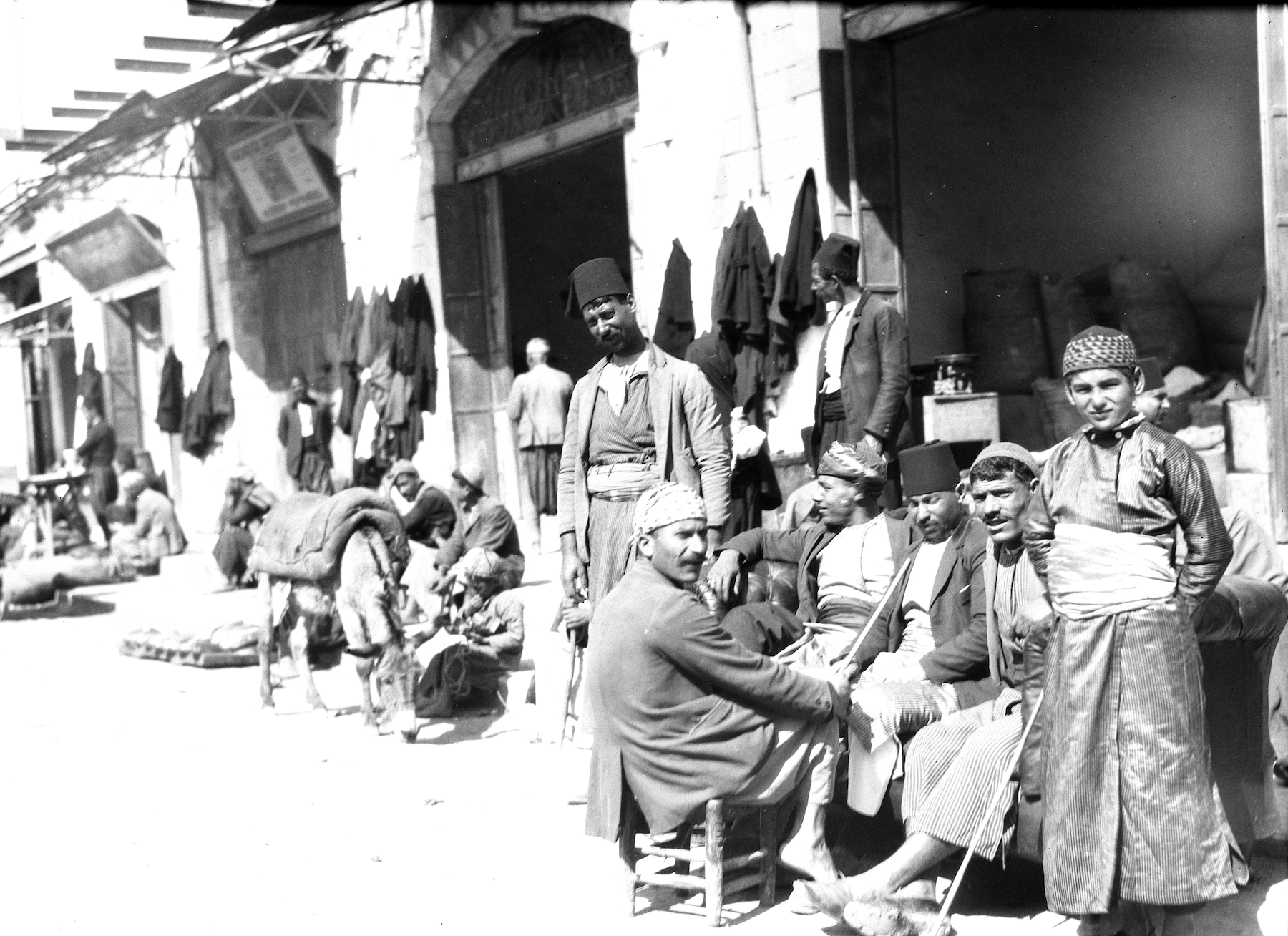

In June 1936, British forces destroyed large parts of the Old City of Jaffa. The army blew up between 220 and 240 multi-occupancy buildings, rendering up to 6,000 Palestinians homeless.

Palestinians in Jaffa in the 1920s. (Frank Scholten, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

While the level of destruction then seems small in comparison to the massive Israeli bombardment in Gaza today, the use of disproportionate force and collective punishment during a military operation felt mainly by civilians is not new to Palestine.

After crushing the general strike that had been declared by the newly formed Arab Higher Committee, with many of the key figures involved imprisoned or exiled, the second phase of the revolt from 1937 saw a large armed uprising sweep through most of the country, reaching its peak in 1938.

To combat this, British forces would take their repression to Palestine’s rural countryside where most of the armed groups were.

Village Raids

To hunt down and eliminate those involved in the uprising, the British regularly cordoned off entire villages, followed by deadly raids. British troops would ransack homes, often destroying property, in search of rebel fighters or weapons.

Palestinian men found with weapons or even bullets were shot dead. Many were killed without any evidence of involvement in military activities.

During raids, British soldiers would often round up the inhabitants and imprison them in open-air pens with barbed wire. Villages would be collectively fined for attacks against British soldiers if the attacker was believed to hail from, or live near, the village in question.

In addition, the homes of suspected attackers and their relatives were demolished, a policy which Israel uses against convicted, or suspected, Palestinian militants today.

Two villages subjected to abuses were al-Bassa and Halhul, which both became the subject of a 2022 BBC report, following a petition from survivors calling for official recognition and an apology from the British government.

This report found that “the historical evidence involved includes details of arbitrary killings, torture, the use of human shields and the introduction of home demolitions as collective punishment.”

It added: “Much of it was conducted within formal policy guidelines for UK forces at the time or with the consent of senior officers.”

Israeli military raids into Palestinians villages in the West Bank are a daily part of life and have escalatedsince Oct. 7, 2023.

Human Shields

British soldiers on an armoured train car with two Palestinian Arab hostages used as human shields, 1936. (Chaim Kahanov and Zecharia Oryon, Jewish Settlement Police, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Another tactic Britain used was to force Palestinian civilians to accompany them on patrols. They were made to sit, unprotected, at the front of military convoys while driving through areas with high rebel activity and even to drive over mines to blow them up before British troops proceeded.

This tactic had come from British rule in India and was known as “minesweeping”. Many Palestinians were killed or seriously injured this way.

Britain effectively used Palestinian civilians as human shields, which Israeli forces have been filmeddoing repeatedly in both the West Bank and in Gaza for years.

In December 2023, two Palestinians, a 15-year-old boy and a 30-year-old man in Gaza, claim they were used as human shields by Israeli soldiers, the boy saying they strapped him with bombs before forcing him into a tunnel. In Israel’s 2014 assault against Gaza, similar allegations were made.

In the West Bank there have been numerous videos showing Israeli soldiers taking Palestinian civilians and forcing them to sit or stand blindfolded in front of Israeli vehicles as they conduct operations.

In some cases, they have even placed civilians onto the front of those vehicles to deter other Palestinians from throwing rocks at invading Israeli forces, just like Britain did during the revolt.

This historical context is especially important to understand now, as Israel has for years accused Palestinian groups like Hamas of using civilians as human shields.

Despite there being little evidence to support this claim (and that the available evidence actually shows Israeli forces doing it themselves) the key historical context is that British troops used it against Palestinian civilians during the Great Revolt.

Orde Wingate & Special Night Squads

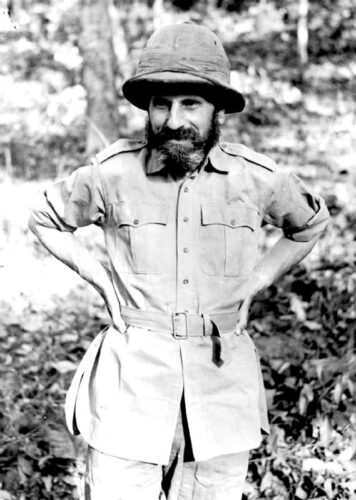

Brigadier Orde Wingate in India in 1943. (No 9 Army Film and Photographic Unit, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The most explicit case of British-Zionist collaboration in repressing the revolt came with the entry into Palestine of the British general Orde Charles Wingate and his creation of the Special Night Squads (SNS).

Wingate, an intelligence officer and committed Christian Zionist, was tasked by the British Army with training Jewish fighters to patrol the Iraq Petroleum Company’s pipeline.

With the SNS, he created his own private militia drawn from recruits within the Haganah, the Zionist military organisation, training them in ambush and assassination tactics.

Describing himself as a firm believer in Zionism, Wingate reportedly told his men that “the Arabs think the night is theirs. The British lock themselves up in their barracks at night. But we, the Jews, will teach them to fear the night more than the day”.

Together with Yitzhak Sadeh, commander of the Palmach, the main strike force of the Haganah, and future founder of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF), Wingate took the SNS on nightly raids against Palestinian villages.

After attacks against the pipeline occurred, his Night Squads would invade nearby villages at dawn, rounding up all the male inhabitants. Forcing them to stand against the wall, the squads then whipped the men’s bare backs.

At times, Wingate would humiliate the villagers, other times he shot them dead. According to Segev, the men under his command said behind his back they thought he was mad.

Israeli military historian Ze’ev Schiff argued that Wingate “left his mark as the single most important influence on the military thinking of the Haganah”.

A lexicon issued by the Israeli Ministry of Defense many years after his death states:

“The teaching of Orde Charles Wingate, his character and leadership were a cornerstone for many of the Haganah’s commanders, and his influence can be seen in the Israel Defense Force’s combat doctrine.”

Two of Israel’s leading future commanders both served under Wingate in the SNS: Moshe Dayan, who became the IDF’s chief of staff and Yigal Allon, a future IDF general and foreign minister.

Dayan said Wingate “taught us everything we know” and that “even when nothing happened, we learned much from Wingate’s instruction”.

Allon described how “by attaching Jewish fighters to his units, he [Wingate] also helped to provide facilities for practical training… He regarded himself, in practice, as a member of the Haganah and that was how we all saw him – as the comrade and, as we called him, ‘the Friend’.”

Major General Bernard Montgomery

General Bernard L. Montgomery watching a tank movement in North Africa, November 1942. (Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

After Wingate, the most notorious British military figure in Palestine during the revolt was Bernard Montgomery. “Monty”, as he was known, was a short-tempered, old-fashioned soldier who rejected any suggestion that the revolt was a national uprising, instead describing the rebels as “bandits”.

He introduced the Bren gun to Palestine, replacing the old Lewis submachine gun the British had been using and gave his men simple instructions on how to deal with the rebels: kill them.

Having previously served in Ireland, launching operations against Irish rebels in 1921, he often made comparisons between the two colonies.

Montgomery was preoccupied with how Britain had lost control of most of Ireland. He thought too many concessions had been made to Sinn Fein. Therefore, his conclusions for Palestine were that Britain should suppress any expression of national identity.

He ordered any Arab caught wearing the chequered headscarf (the Keffiyeh) to be “caged”. He also floated the idea of chaining people’s legs as punishment.

Since Israel’s own military occupation of 1967 began, authorities there have repeatedly waged campaigns against Palestinian national symbols. The Palestinian flag has been targeted across the West Bank, Jerusalem and inside Israel itself and is regularly removed from public view and confiscated.

Much like the British during the revolt, Israeli authorities see Palestinian national identity as a threatand work to stamp it out.

A.Bustos is a researcher with a masters degree in Near and Middle Eastern studies from SOAS University of London and before that studied history and politics. He works as the assistant director at Palestine Deep Dive.

This article is from Declassified UK.

Views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Consortium Ne