“As Mr. Yakub continued to preach for converts, he told his people that he would make the others work for them. (This promise came to pass.) Naturally, there are always some people around who would like to have others do their work. Those are the ones who fell for Mr. Yakub’s teaching, 100 per cent.”

—The Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad, chapter 55 of Message to the Blackman in America titled “The Making of Devil”

“Three blessings a Jewish man is obligated to pray daily: ‘(Blessed art Thou,) Who did not make me a gentile; Who did not make me a woman; and Who did not make me a slave.’”

—Babylonian Talmud, Menahot 43b–44a[*]

The story of the Jewish American experience that most Jews want to believe, and want the world to believe, is one of almost endless historical victimhood. They insist that they fled anti-Semitic oppression in Europe, landing safely on Ellis Island long after the Civil War’s end in 1865, and certainly some did. By their hard work, strong religious bonds, and reverence for communal education they succeeded against all odds, becoming, as Isaiah exhorts,[1] “a light unto the world.” As their story goes, they altogether eluded the ugly business of plantation slavery—but had they been here, they assure us, Jews would have been leading the abolitionists. After all, their own alleged enslavement to Pharaoh would have made them—of all the groups of Caucasian people—more sympathetic toward Black suffering.

To a trusting, Bible-believing people this Jewish self-portrait sounds plausible and is consistent with a Christian doctrine that sanctifies God’s Chosen People, the so-called Children of Israel (Deuteronomy 7:6–11). But the people who today call themselves Jews have now collided with their own Jewish scholars and historians who have presented an entirely different and far more troubling story about American Jewish history and the central role of Jews in the greatest crime in world history—the Black African Holocaust.

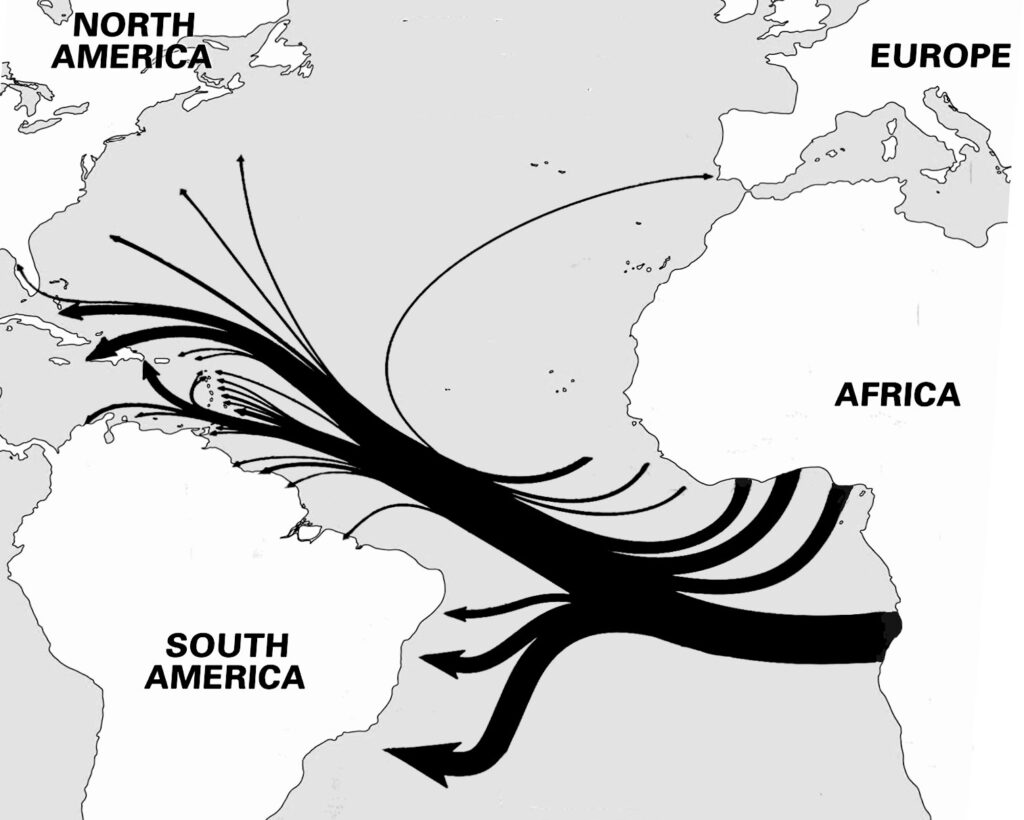

For the most part, Americans—white and Black—are entirely unaware that when the trans-Atlantic slave trade began in the 1500s, it was focused on shipping enslaved Africans to the sugar plantations of South America and the Caribbean islands centuries before expanding to the cotton fields of the American South in the mid-1700s. In the entire history of slavery in the western hemisphere as many as 9 out of 10 stolen Africans were shipped to those tropical climes—not to Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, or South Carolina. The map below illustrates by the thickness of the arrows the relative proportions of Africans shipped to the New World, and, as shown, relatively few made it into what was to become the United States.

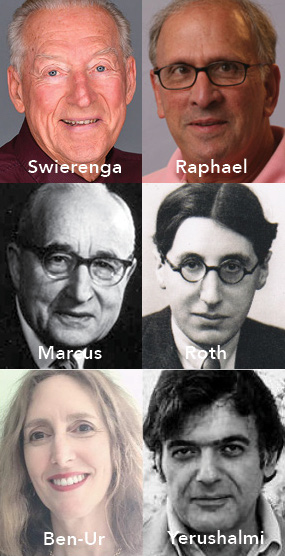

And all during this unprecedented racial tragedy Jews claim they were preoccupied in Europe, nowhere near the scene of the crime. Dr. Robert Swierenga very directly challenges that oft-repeated Jewish alibi (emphasis ours):

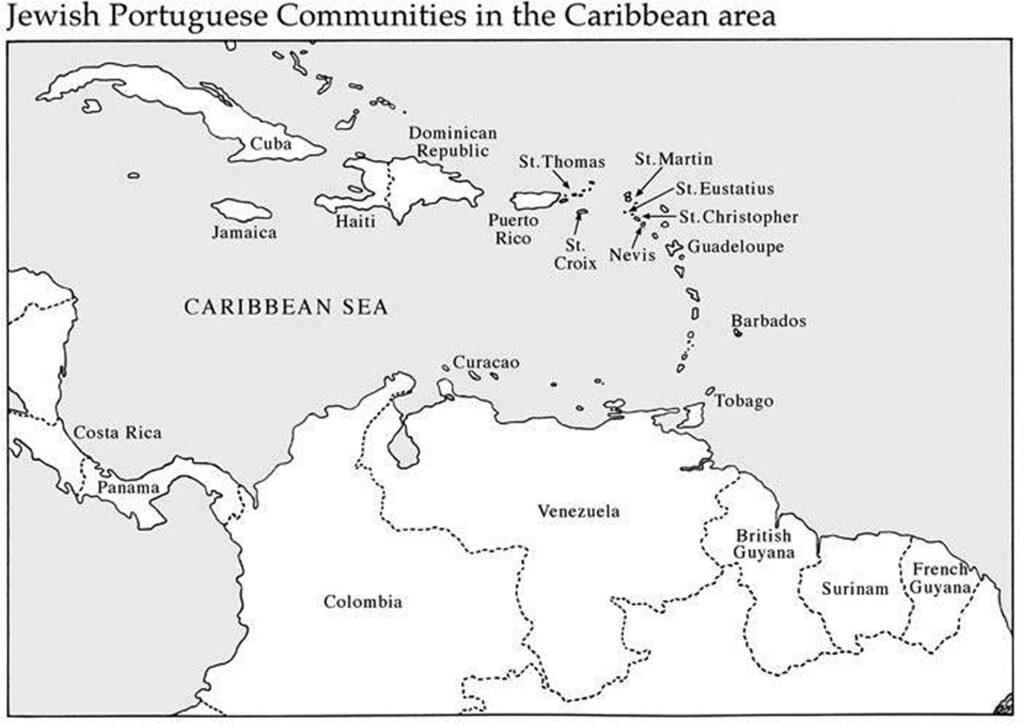

“At the birth of the United States in 1787 the Jews of the slave islands [Caribbean] outnumbered those in North America by five times and may have equaled those in England. Surinam had fourteen hundred Jews and Curaçao fifteen hundred—both nearly one half of the total white population. By contrast, the entire United States in 1790 numbered less than fifteen hundred Jews.”[2]

Seeking Religious Liberty?

But doesn’t this early Jewish presence in the “slave islands” conflict drastically with the prevailing image of the Jews as freedom-loving religious refugees? This is the perfect time to have an adult conversation about the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the Jewish role in it, and we must start by putting to bed the infantile notion endemic in this Jewish American fairy tale that Europeans sailed across the ocean “seeking religious liberty.” Every school child learns about the brave and pious Pilgrims who sailed to Plymouth on the Mayflower in 1620 “seeking religious liberty” from the tyrannical king of England. But the reality is that the “Pilgrims” were under contract with a private business named the Company of Merchant Adventurers, which expected them to acquire lumber, beaver and otter furs, and any other riches to be found or stolen. Thus, the “Pilgrims”—who referred to themselves as “separatists,” not as “pilgrims”—worked under contract to a private enterprise whose investors cared nothing about religion. More than a century before those Separatists, a Spaniard named Christopher Columbus was privately financed for his infamous voyage of discovery in 1492, by a wealthy Jew named Luis de Santangel. According to Simon Wiesenthal, in his book Sails of Hope (p. 168), “But for this man, Columbus’s expedition would never have taken place.” A practiced slave dealer, Columbus captured 600 of the aboriginal people he encountered to auction off back in Spain. And so it is with the Jewish newcomers who were seeking profits in sugar, cotton, tobacco, and other riches of the New World. Jewish scholar Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi describes them:

“[T]hese Jews engaged in an almost untrammeled range of economic activity, bore arms in the militias, owned land and ran plantations, and were represented in local councils. They had arrived at the closest point to full legal equality possible for Jews prior to the emergence of the modern nation-state.”[3]

They were seeking not “religious freedom” but the freedom to trade on an international scale. In fact, when they were first barred from acquiring Black slaves in the colonies they entered, the Jews considered it an act of “anti-Semitism.” The riches they sought could not be extracted without free and forced African labor. And as Jewish merchants followed their Yakubian directive—making others work for them—this is where the Black–Jewish relationship in the West truly begins.

In fact, there are scant references to the Jewish faith, Judaism, in any of the extant records of these early Jewish settlers. Nothing about Moses, Aaron, The Ten Commandments; no mention of the Ark of the Covenant; and nothing about being any “Light unto the Worlds.” If there were no profit in it, there was no “Jew” in it—and there was plenty of profit in Black slavery.[4]

Surinam, located in northeastern South America, holds the distinction of having the oldest Jewish community in the Americas, Jews having formed a synagogue in 1665. British Jewish historian Dr. Cecil Roth tracks them in his History of the Marranos: “The Jews of [Surinam] were also foremost in the suppression of the successive negro revolts, from 1690 to 1722: these as a matter of fact were largely directed against them, as being the greatest slave-holders of the region.

And here is where—unbelievably—we find the first inkling of the Jewish religion. The very first published Jewish prayer in their New World paradise, was a prayer titled “Old Hebrew Prayer in Time of Revolt of the Negroes,” in which the rabbi asked their God to give them strength “to conquer and destroy beneath their feet all cruel and rebellious Africans, our enemies who are planning evil against us….Amen.”[5]

Roth continues: “These disturbances, together with the inroads of the climate, led ultimately to the abandonment of the settlement, of which nothing but the ruin now remains.” Dr. Roth hits on a theme here that may be difficult for most to comprehend. Not only were Jews present in the Americas long before the actual founding of the United States, but they were “the greatest slave-holders” in one of the major destinations of enslaved Africans. Further, these same “liberty-seeking” Jews actually went to war against the Africans that had escaped from Jewish plantations! Scholar Steven Sallie:

“There is little dispute, however, that Jews were quite often in charge of raiding adventures and the severe punishing of the maroons [escaped slaves]. In response to the cruelty of some Jews, maroons quite often attacked selected Jewish plantations. These Jewish-African conflicts were numerous, well organized, and persisted into the 1800s. Given their names, the leaders of the maroons tended to be Muslims.”[6]

One must also note that the decorated scholars quoted above spoke of “Jews” as a collective, neither making any qualification about the term that would limit responsibility or culpability to “some” or “a party among” or “a portion of” the Jewish community. This is particularly important given the magnitude of the crime they are describing—Black slavery.

Two major Jewish historical associations concur with, and elaborate on, this generally unknown aspect of the Jewish role in Black slavery. The American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS) is the oldest and most prominent, having its founding in 1892. Rabbi Marc Lee Raphael was its longtime editor of its publications when he wrote in 1983 that in the Caribbean and South America,

“Jewish merchants played a major role in the slave trade. In fact, in all the American colonies, whether French (Martinique), British, or Dutch, Jewish merchants frequently dominated. This was no less true on the North American mainland, where during the eighteenth century Jews participated in the ‘triangular trade’ that brought slaves from Africa to the West Indies…”

“FREQUENTLY DOMINATED” and “played a major role” are the terms Rabbi Raphael used almost a decade before the Nation of Islam published its never-refuted book on Jews and the slave trade, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, Vol. 1. Drs. Swierenga, Sallie, Raphael, and Roth are all addressing a startling duality in the 500-year Black–Jewish relationship—that the Jewish self-image of a biblical people yearning for freedom directly contradicts the actual fact that the Jewish people were attracted to, and often dominated the economies in, the very places where existed the most brutal forms of chattel slavery.

The American Jewish Archives (AJA) was founded in 1947 by the “Dean of American Jewish scholars,” Rabbi Jacob Rader Marcus,[7] and is the repository of “ten million pages of documentation” on Jewish history in the Americas. Turns out, the AJA has a lot to say about these early “oppressed” Jews who migrated from Europe and somehow found unprecedented prosperity in the “slave islands.” In several articles the AJA casually makes several references to the interdependent relationship between the most brutal forms of slavery and the Jewish pilgrims: “[I]ndividual Jews can be found on almost every island of the Caribbean prior to the abandonment of slavery in the mid-nineteenth century,”[8] thus firmly linking slavery to the Jews’ very presence.

In the plantation colony of Surinam the AJA points out that Jews “fared well, thanks to the abundance of slaves and plantations…”[9] Rabbi Dr. Raphael adds that

“Slave trading was a major feature of Jewish economic life in Surinam, which was a major stopping-off point in the triangular trade. Both North American and Caribbean Jews played a key role in this commerce: records of a slave sale in 1707 reveal that the ten largest Jewish purchasers spent more than 25 percent of the total funds exchanged.”[10]

A more recent analysis of Surinam’s Jews by Dr. Aviva Ben-Ur only solidifies this linkage and adds to the horrors:

“The liberty Jews enjoyed…was inextricably intertwined with violent coercion….African slaves were routinely tortured on the village’s roadsides or along the fence enclosing the synagogue square.”[11]

The AJA hits on a theme that is repeated over and over again: “the abolition of the slave trade in 1819 and the formal emancipation of slaves in 1863 made plantations unprofitable and so decimated Jewish trade that [the Jews] all but disappeared.” Recognize the import of that statement: the freeing of the Black slaves “DECIMATED” and “DISAPPEARED” the Jewish community.

Jews had a presence on the island of Barbados in about 1628 and historian Stephen Fortune wrote that “the reputed prosperity of the Jews contrasted with the inexcusable and disgraceful plight of the slaves.”[12] Jews flocked to this hell on earth, and here again the AJA sounds the uniquely Jewish refrain: “Unfortunately, economic depression resulting from the earthquake and the emancipation of slaves led to the emigration of many of the island’s Jews.”[13] They pose the freeing of African slaves as a disaster equal to that of an earthquake—causing the “unfortunate” Jews to permanently flee.

The Encyclopedia Judaica (EJ) reports that the island of Curaçao was called the “Mother of the Caribbean Jewish communities,” yet Jewish scholars describe the island as a distribution center for the slave trade[14]— “a large slave depot.”[15] The AJA affirms that “The slave trade helped Curaçao to prosper, and her Jewish community grew rapidly,” even building a synagogue “for the convenience of the plantation owners who lived outside of the city.”[16] In fact, Jews owned 80 percent of Curaçao’s plantations, and Jewish slave traders were responsible for distributing the slaves from Curaçao to the Spanish American ports throughout the Caribbean and South America.[17] In 1765, the Jesurun family owned a record number of 366 Black people; the closest Gentile had 240 slaves. In one documented case in 1701, the Jewish Senior brothers arranged the shipment of 664 Africans; 205 perished en route to Curaçao.[18] And historian of the island Johan Hartog confirms a familiar Jewish theme—that the Jewish community suffered a “steep decline” the same year that the slave trade was curtailed.[19]

When Jews settled in Haiti, the Encyclopedia Judaica admitted,[20] they “specialized in agricultural plantations [but] with the slave revolts at the end of the 18th century, Jews gradually abandoned Haiti for other Caribbean islands or for the United States (New Orleans, Charleston).” Here again Jews are not sticking around for Black freedom; nor were they part of the process of achieving it. As soon as emancipation becomes a reality, Jews abandon Haiti for slavier environs.

Jamaica also had a robust Jewish colony, writes the AJA (p. 151): “The growth of the sugar industry enlarged the Jewish immigration and a number of Jews became plantation owners.”[21] The EJ boasted that “Jews with agricultural plantations controlled the sugar and vanilla industries, and …were the leaders in foreign trade and shipping.”[22] In its section on “Sugar”—the product most responsible for the enslavement of millions of Africans—the EJ puts Jews at the epicenter:

“The Jews of Brazil were not important as proprietors of [sugar] mills but rather as financial agents, brokers, and export merchants. When Brazil came again under Portuguese rule in the second half of the 17th century, many Jews emigrated to Surinam, Barbados, Curaçao, and Jamaica, where they acquired large sugarcane plantations and became the leading entrepreneurs in the sugar trade.”[23]

And then it reveals the other, now predictable, Jewish reality: “The abolition of slavery in the British dominions (1833) lowered the economy and scattered the Jews.” Note here the AJA writes that freedom for enslaved Blacks “scattered” the Jews.

Many of those Jews “scattered” to the North American mainland, says the AJA: “The end of slavery in the Caribbean saw Jews from the islands arriving almost daily…” Many ended up in the colony of Georgia, described as “suffering from the trustees’ idealistic insistence on no slaves or liquor…”[24] As the AJA frames it, “no slaves” meant Jewish “suffering.” In fact, the refusal of the leaders of Georgia to permit Black slavery triggered a Jewish exodus from the colony! By 1740 only three Jewish families were left. They bounced, according to Rabbi Marcus, because “Negro slavery was prohibited, the liquor traffic was forbidden.”[25] Jew Abraham De Lyon said he left for “the want of Negroes…whereas his white servants cost him more than he was able to afford.”[26]

From their own archival documents the most lettered Jewish scholars have painted an alarming portrait of the earliest of their founding fathers. In every case examined, Jewish “liberty” and prosperity were entirely dependent on Black slavery, and once Black “liberty” was achieved the Jewish world imploded and the Jews fled. The Encyclopedia Judaica summarizes nicely:

“A general decline of the Spanish-Portuguese communities in the Caribbean set in during the 19th century. Growing competition in agricultural products, the abandonment of the plantations by the Afro-American laborers due to the abolition of slavery, assimilation, and emigration were the main causes of this decline.”[27]

The Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad wrote that after being bound in Europe for 1,000 years, “they were loose (free) to travel over the earth and deceive the people.” Further, “They have been here now over 400 years. Their worst and most unpardonable sins were the bringing of the so-called Negroes here to do their labor.”[28]

Jewish scholars have thus affirmed that no one better fits Mr. Muhammad’s description of the traveling deceiver and “unpardonable” slave-making sinner than the Jew.

NOTES

[*] See also Michael Hoffman, Judaism Discovered (2008), p. 375.

[1] Isaiah 42:6; 49:6; 60:3.

[2] Robert Swierenga, The Forerunners: Dutch Jewry in the North American Diaspora (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994), p. 36.

[3] Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, “Between Amsterdam and New Amsterdam: The Place of Curaçao and the Caribbean in Early Modern Jewish History,” American Jewish History, vol. 72, no. 2 (December 1982), p. 190.

[4] Yda Schreuder, Amsterdam’s Sephardic Merchants and the Atlantic Sugar Trade in the Seventeenth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), p. 70. Also, Steven S. Sallie, “The Role of the Semitic Peoples in the Expansion of the World Economy Via the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade: A Literature Extraction and an Interpretation,” Journal of Third World Studies, vol. 11, no. 2 (Fall 1994), p. 173.

[5] “Miscellaneous Items Relating to Jews of North America,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, vol. 27 (1920), pp. 223–24.

[6] Sallie, “The Role of the Semitic Peoples,” p. 173.

[7] https://www.americanjewisharchives.org/about/jacob-rader-marcus/

[8] Malcolm H. Stern, “Portuguese Sephardim in the Americas,” American Jewish Archives, vol. 44, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 1992), p. 142.

[9] Allan Metz, “Those of the Hebrew Nation…The Sephardic Experience in Colonial Latin America,” American Jewish Archives, vol. 44, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 1992), p. 226.

[10] Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in the United States: A Documentary History (New York: Behrman House, 1983), p. 24.

[11] Jewish Autonomy in a Slave Society (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), p. 76.

[12] Stephen Alexander Fortune, Merchants and Jews: The Struggle for the British West Indian Caribbean, 1650-1750 (Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1984), p. 109.

[13] Stern, “Portuguese Sephardim in the Americas,” p. 143.

[14] Lavy Becker, “A Report on Curacao,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, December 5, 1969.

[15] Daniel M. Swetschinski, “Conflict and Opportunity in ‘Europe’s Other Sea’: The Adventure of Caribbean Jewish Settlement,” American Jewish History, vol. 72, no. 2 (December 1982), p. 236.

[16] Stern, “Portuguese Sephardim in the Americas,” p. 147; Emma Fidanque Levy, “The Fidanques: Symbols of the Continuity of the Sephardic Tradition in America,” American Jewish Archives, vol. 44, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 1992), pp. 184–85.

[17] Marc Lee Raphael, Jews and Judaism in the United States: A Documentary History (New York: Behrman House, 1983), p. 24.

[18] Isaac S. and Susan A. Emmanuel, History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles(Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 77.

[19] Johan Hartog, Curaçao From Colonial Dependence to Autonomy (Aruba, Netherland Antilles, 1968), p. 276.

[20] Second Edition, Volume 4, p. 473.

[21] Stern, “Portuguese Sephardim in the Americas,” p. 151.

[22] Second Edition, Volume 4, p. 474.

[23] See also James C. Boyajian, “New Christians and Jews in the Sugar Trade, 1550–1750: Two Centuries of Development of the Atlantic Economy,” in The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1450-1800, eds. Paolo Bernardini and Norman Fiering (New York: Berghahn Books, 2001), p. 476.

[24] Stern, “Portuguese Sephardim in the Americas,” p. 164.

[25] Jacob Rader Marcus, Memoirs of American Jews 1775-1865, vol. 2 (New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1974), p. 288.

[26] Edward D. Coleman, “Jewish Merchants in the Colonial Slave Trade,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, vol. 34 (1938), p. 285.

[27] Second Edition, Volume 4, p. 470.

[28] Message to the Blackman in America, pp. 104, 267; “Is There a Mystery God?” Pittsburgh Courier, Aug. 18, 1956.