At the Democratic National Convention, I heard more about Trump’s policy agenda than Harris’s.

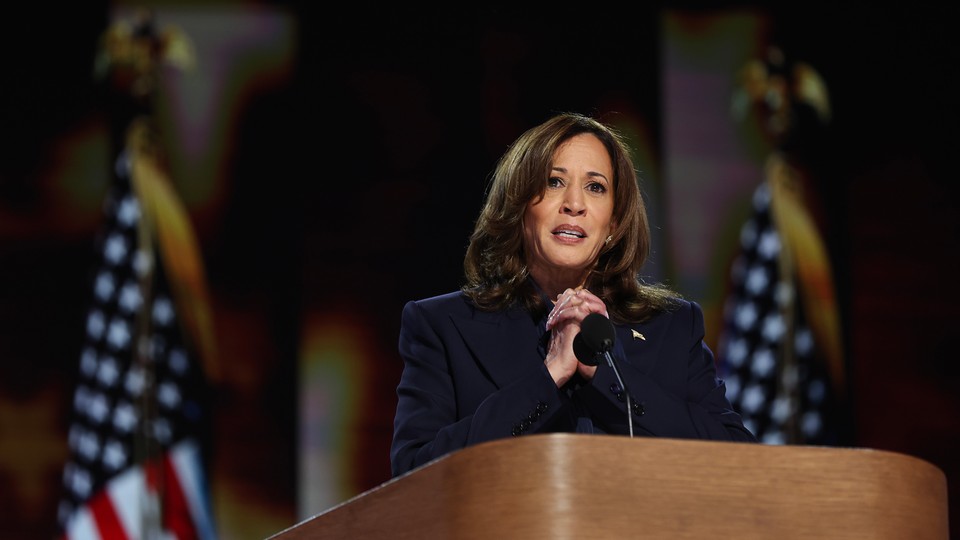

Justin Sullivan / Getty

The election is a “fight for America’s future,” Kamala Harris said in her speech to the Democratic National Convention tonight. She painted a picture of what a second Trump presidency might look like: chaotic and dangerous. Donald Trump would take the country back, whereas she would take the country forward. “I will be a president who leads and listens; who is realistic, practical, and has common sense, and always fights for the American people,” she said.

How she’ll fight, well, that’ll be worked out after Election Day. Harris did mention some specifics in her speech: She’ll push through the recently derailed bipartisan immigration bill, for instance. For the most part, though, Harris pointed to large goals, like ending the housing shortage, and affirmed general commitments, like supporting NATO.

According to multiple campaign advisers and Democratic officials, this campaign is for laying out a vision, for convincing voters that Harris is on their side, and for getting to 270 electoral votes. In 2019, I worked briefly for Harris’s primary campaign before becoming a journalist, and I remember how wonky the environment felt. Over the four days I spent among the Democrats in Chicago this week, I didn’t hear the words white paper or study one time.

In fact, I probably heard more about Trump’s policy agenda than Harris’s. Democrats have repeatedly brandished Project 2025 onstage, calling attention to the 900-page presidential-transition blueprint produced by the Heritage Foundation. Harris mentioned it tonight, too. But Harris has no Project 2025 equivalent. And Democrats seem at peace with that.

Senator Brian Schatz of Hawaii told me outside the convention center yesterday that the policy-light approach has two advantages: “One is that you are simply giving your opponents less to shoot at, mischaracterize.” Fair enough. Trump has sought to distance himself from Project 2025 and its controversial right-wing proposals while trying to tar Harris as a “radical leftist lunatic.” Both of these efforts, so far, have failed.

Schatz also believes that avoiding policy prescriptions is actually “a little more honest with the voter.” According to Schatz, even if Harris wins, her policy agenda will be constrained by the makeup of Congress and committee assignments. Why get into details that won’t matter?

But perhaps the greatest advantage of a blank policy slate is that it allows for wish-casting. Why, I asked Schatz, did both progressive and moderate Democrats seem excited by Harris? “When a party is united, members of the coalition project their hopes and dreams onto their nominees,” Schatz replied.

So that’s what all the much-discussed good vibes are about. For the time being, the major factions of the Democratic Party seem to believe that when push comes to shove, they can win out.

In 2020, a bitterly fought Democratic primary resulted in unity panels where the progressive and moderate camps came together to find middle ground. Four years earlier, Hillary Clinton similarly forged connections with the Bernie Sanders side to form a consensus platform. But Harris, who of course achieved the nomination without suffering any primary at all, achieved unity without any policy fight at all.

DaMareo Cooper, a co-executive director of the progressive organization the Center for Popular Democracy, told me he thinks that the “moderates are reading [Harris] wrong” and that “everyone moves to the middle when they’re in the presidential campaign.” Cooper doesn’t disapprove of “someone who’s running for president [to say,] ‘I’m representing all people in this country.’” But as his co-executive director, Analilia Mejia, put it, Harris represents a continuation of the “most progressive administration in my generation.”

That’s not what moderates believe. “Kamala Harris was a center-left candidate and Tim [Walz] was a center-left member of Congress and so we know we can work with this administration,” Representative Annie Kuster, the chair of the New Democrats Coalition, a moderate faction of the party, said at a centrist-Democrats roundtable on Tuesday.

The debate over Harris’s price-gouging proposal captures this wish-casting dynamic. Last week, the campaign announced it would put forward measures to “bring down costs for American families.” One of those measures was a “first-ever federal ban on price gouging,” which some commentators took to mean that Harris would try to impose price controls. But when Harris delivered a speech on the subject days later, many observers came away with the impression that the vice president merely intended to expand the protections many states already have, and to go after a few bad actors. Advisers spread the word that the policy would apply only during crises and to food, and would have no automatic triggers.

Is Harris’s plan radical, moderate, or something else? Democrats’ perception of it seems to have a lot more to do with their personal preferences than with anything objective.

Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear, a centrist Democrat, told me that “price-gouging statutes have been around a long time” and pointed to his own use of them: “People are making a big deal out of it, but it’s not new at all.” Similarly, Kuster immediately rejected the idea that Harris was proposing anything extreme. “She’s not talking about price controls,” she said, waving her hands dismissively. “She’s talking about lower prices and lowering costs for hardworking American families.”

But Senator Bob Casey was under the impression that Harris had effectively endorsed the expansive price-gouging bill he co-sponsored with Senator Elizabeth Warren, which prohibits the practice in all industries. He said as much in a press release and noted that Harris will fight price-gouging in his remarks to the convention this evening.

When I asked the Harris campaign for clarity, a senior campaign official told me that Harris was not supporting price controls, nor would her proposal to go after price-gougers apply beyond food and grocery stores. After some prodding, the official confirmed that this meant Harris had not endorsed the Warren-Casey bill, but didn’t rule out that someone on the campaign had told Casey otherwise. The official also echoed Schatz’s argument that adding in too much detail could be deceptive given that the real policy-making process requires time, effort, and negotiation.

At any rate, vagueness is politically useful. Hints at economic populism buoy the progressives while whispers of moderation let centrists feel that nothing major is afoot. Win-win-win. But how long can it last?

As she campaigns for the presidency, Harris is getting to be everything to everyone, the generic Democrat who does so well in surveys. But once she starts laying out specific policy proposals, some Democrats are going to have their hopes dashed. They’re going to remember the divisions that had racked the party so thoroughly during the Biden administration, and the infighting will be cutthroat. But, as Colorado Governor Jared Polis told me this morning, those debates are for “after the election.”