140 years after imperial powers at the Berlin Conference carved up the continent and its resources, Africa’s leaders are still trooping to global centres of capital, committed to selling the continent down the river.

Photo courtesy: FOCAC 2024

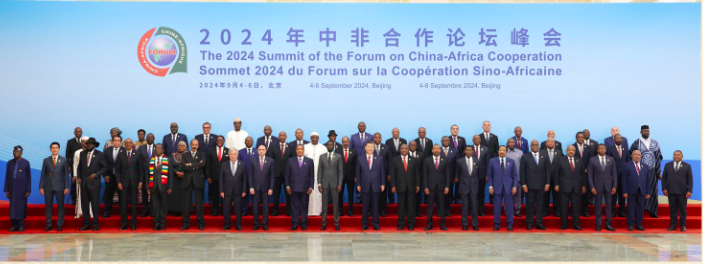

The just ended Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) has become the latest in a resurgence of gatherings by global powers to win friends and influence Africans, for the usual asymmetric and lopsided deals.

Chinese President Xi Jinping used the September 4-6 forum to strengthen trade and military ties with African countries – promising almost $51 billion in financing to African countries over the next three years, and pledging to put them at the forefront of a global “renewable energy revolution”.

The Chinese leader also promised to help create at least 1 million jobs for Africa and $141 million in grants for military assistance, saying Beijing would provide training for 6,000 military personnel and 1,000 police and law enforcement officers from Africa. This is significant. Since its re-engagement with Africa at the turn of the century, Beijing has studiously avoided engaging African states on military and security matters, wary of muscling in on what is perceived as Western territory. However, in a joint statement, Xi and the 50 African leaders present agreed to work together to build an “equal” and “orderly multipolar world” and “universally beneficial and inclusive economic globalisation”.

Africa is the largest regional component of China’s ambitious $1 trillion Belt and Road initiative (BRI) to reset global commerce. But the scheme has for some time now received a backlash from African critics who worry that it is fuelling a new debt crisis on the continent. An added wrinkle is that many of China’s BRI infrastructure projects are plagued by construction flaws. Uganda’s power generation company recently said it has identified 584 construction defects in the Chinese-built 183-megawatt Isimba Hydro Power Plant. It cited the failure by the China International Water and Electric Corporation to build a floating boom to protect the dam from weeds and other debris, clogging up turbines and causing power outages.

In Angola, occupants of the vast Kilamba Kiaxi social housing project are complaining about cracked walls, mouldy ceilings, and poor construction barely 10 years after its inception.

At the just-ended FOCAC, China was keen to repair the cracks, both literal and figurative, that have become the hallmarks of its global mega-projects. However, with its growth curve flattening after major economic miscalculations during the COVID lockdown, it is expected that China will focus its funding largesse on more bite-sized projects, like beautifying African cities, boosting agriculture, and reducing poverty.

FOCAC comes hard on the heels of similar Africa-plus-One summits, now the centrepieces of Africa’s engagement with global powers, great and emerging. Earlier in June during the inaugural Korea-Africa Summit, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol promised to expand development aid to Africa and pursue deeper cooperation with the region of 1.4 billion people on critical minerals and technology. The eastern Asian nation also committed $14 billion in export financing to support its companies investing in Africa while increasing its official development assistance (ODA) to $10 billion by 2030.

140 years since the Berlin Conference for the partition of the continent’s territory and resources by European hegemons, African leaders are still trooping en masse to sign new treaties that give away the continent’s natural resources at prices barely above the rates negotiated by their late-19th century ancestors. And although there is much greater African agency today, the key question on many lips is who genuinely represents African interests given the crises of legitimacy, accountability and good faith faced by almost all the African leaders who so willingly troop to the world’s capitals at the slightest whim of the convenors.

“The expanding number of partners means that African leaders have more choices to find mutually beneficial partnerships,” Joseph Siegle, director of research of the Washington DC-based Africa Center for Strategic Studies, tells African Arguments in an email. “[But] without transparency and ownership from the public, the risk is that these deals will only benefit a small, well-connected segment of these societies.”

The First Ladies of FOCAC. Photo courtesy: Xi’s Moments.

Jesper Bjarnesen, Senior Researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute, notes that although the many summits between African leaders and other global actors confirm that Africa commands a measure of global attention considerably more than it did some decades ago and, to some extent, is able to leverage this in dealings with the rest of the world, the interests and agendas of African leaders are “complex” and not always necessarily in the best interest of their constituents.

“In other words, although these summits are politically significant, they are perhaps less consequential [as a site of] genuine collaboration,” Bjarnesen tells African Arguments in an email. “[Another] question is [whether] global actors such as China, Russia as well as the EU and the US are engaging in this way to deepen genuine collaboration or to send a message to competing global powers.”

‘Asymmetric and lopsided summits’

Despite firm promises by several African heads of state not to attend ‘Africa +1 Summits, the committed turnout in Rome for the one-day summit hosted by the right-wing Italian leader, Georgia Meloni, arguably marked a new low. Photo: Paolo Giandotti (Official photographer, Presidenza della Repubblica)

During the second U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit which was held from 13-15 December 2022, President Joe Biden announced that the US was investing $55 billion in Africa over the next three years. Offers, more grand gestures than committed finance, have thickened the stew of 21st century African summit diplomacy. The India–Africa Forum Summit, first held in New Delhi in 2008, is a political platform that takes place every three years to strengthen diplomatic and political cooperation between India and 54 African Union countries.

Moscow, for its part, pledged to expand and diversify trade with Africa to US$40 billion within five years during the inaugural Russia-Africa Summit from 23-24 October, 2019. Meanwhile, for the first time since the inaugural event in 1973, the Franco-Africa Summit – rebranded the New Africa-France Summit – was held on October 8, 2021 in Montpellier, France with a radically different format: nearly 3,000 youth from Africa and France took part, with no heads of state in attendance save for French President Emmanuel Macron.

In 2022, the European Union and the African Union signed a $170 billion development package as part of an investment blueprint that sought to mobilise up to 300 billion euros ($328 billion) for public and private infrastructure around the world by 2027.

Earlier this year, the government of Italy unveiled a €5.5 billion plan to support African development at a one-day Italy-Africa summit in Rome.

Paul Nantulya, the research associate and China specialist at the Washington-based Africa Center for Strategic Studies, argues that Africa-plus one-summits are “asymmetric” and “lopsided” in nature.

The stronger partner, he notes, always has far better leverage than the African side. France, China, Japan, EU, and now Korea, all have well-defined strategies for engagement with Africa that are refined periodically. African countries, on the other hand, do not have identifiable strategies for engagement with foreign powers.

“African countries do have an opportunity to improve their negotiating positions. So far, it would seem like the political will and policy imagination are lacking. They seem to think that leverage only depends on numbers, which is a costly mistake,” Nantulya tells African Arguments.

To solve the problem, Nantulya suggests that the African Union and African countries should establish a “shared responsibility system of collective representation” where AU members agree to establish an African High Commission for External Engagement within the AU structure. Such a Commission would assign 6-7 African countries to handle each external partner and ensure collective representation.

“Hence for instance, you would have no more than seven African presidents going to the Africa-Plus Summits, as opposed to 54,” explains Nantulya, adding that this will make it “cheaper, more effective, focused, and strategic.”

“The country [leaders] could serve for a period of 2-3 years and then rotate as needed. The representation should cover all regions (North, Central, South, East, and Diaspora). This is a much better way to manage these Summits.

“The current system of 54 Presidents trooping to different capitals when called upon is unsustainable, and sends a very wrong message,” he said.

While African leaders tend to break ranks during the different summits, the Nordic Africa Institute’s Jesper Bjarnesen, identifies a kind of “diplomatic or political division of labour” in which different global actors emphasise particular themes or sectors in their relationships with African states. While Russia is threatening Washington’s dominance in the security sector, China, and to some extent India, emphasise infrastructure and trade, he says.

“Countries like Turkey, China and Russia are challenging that model by offering similar investments but with a more covert political/ideological agenda,” says Bjarnesen. “The Gulf states seem to me to be mainly engaging African states through loans and credit schemes that are challenging the programmes and accompanying conditionalities of the Bretton-Woods institutions – the World Bank and IMF.”

The EU, meanwhile, represents states with long and troubled historical ties to the African continent – a history of exploitation, conquest and dependency that is now being reopened for critical scrutiny.

Macharia Munene, Professor of History and International Relations at the Nairobi-based United States International University-Africa (USIU-A), says the Africa-plus-One-summits are “insulting” to the continent given that the host carries the presumption that Africans are “cheap and easy to manipulate”.

“The promises of goodies to be obtained are like showing candy or chocolate to little boys and girls,” Munene told African Arguments.

The bipolarisation of Africa-plus one-summits

Ideological engagement? South Africa’s former Foreign Minister, Naledi Pandor and Russia’s FM, Sergey Lavrov at the low-key Russia-Africa Summit and Economic Forum in July 2023. Photo courtesy: Russia-Africa Economic Forum.

Andrew Korybko, a Moscow-based American political analyst specialising in the global systemic transition to multipolarity says the “Fourth Industrial Revolution”/“Great Reset” (4IR/GR) will define global economic trends over the coming decades, with all related technologies dependent on certain critical minerals like cobalt, many of which are located in Africa. China, says Korybko, currently controls most of that mineral’s production as well as lithium. This explains why its competitors want to diversify from their dependence on China’s supply chains, ergo the rush to extract African resources, much like the Republic of Korea sought to do via its inaugural Africa Summit.

“China requires reliable access – and from its perspective, privileged access as well – to these minerals and equally reliable (and privileged) access to their markets in order to continue growing, which the US and its like-minded partners want to deny it in order to manage China’s rise,” Korybko told African Arguments.

“While the West still attaches political strings to its loans, its non-Western partners like the Republic of Korea, the UAE, and India follow the Chinese model of eschewing such requirements, though they’re also much more careful to avoid inadvertently fuelling corruption,” Korybko said.

He believes this approach might “resonate much more with the masses” – some of whom have begun to espouse anti-government sentiment over the past decade as a reaction to BRI-related corruption. “The larger context within which this is unfolding concerns the New Cold War competition between China and the US over the future of the ongoing global systemic transition.”

Similarly, Mohamed Kheir Omer, an African-Norwegian researcher and writer based in Oslo, Norway, views the Africa-plus-One summits as a new phenomenon in the current transition period to a multi-polar world characterised by increased competition to win Africa and exploit its resources. The former member of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), however, sees little difference in the offers of the different summits from a multipolar standpoint.

“For instance, European countries are more [preoccupied] with stemming immigration to Europe, and the better you serve them, the more aid they are willing to provide,” Mohamed tells African Arguments in an email.

He said other international partners either want “easy access” to raw materials or markets, with no interest in helping African countries to industrialise or add value to their products. “Gulf countries have also entered the competition,” Mohamed says.

“We cannot continue to blame others for our own failures, not to pursue our interests. Africa is divided; different countries have different interests and it may be difficult to speak with one voice.”

Régis Hounkpè, the Beninese geopolitical scientist and director of Interglobe Conseils, a company specialising in global politics describes the nature of cooperation between Africa and global powers as “pragmatic”, and built on “vested interests”, with each hegemon seeking to expand their sphere of influence.

“Russia’s cooperation with certain African countries is more security- and military-related than structural; it does not seem judicious to me compared to China or Japan,” Hounkpè observes. “China’s cooperation with Africa, [meanwhile], is strategic in nature and this allows her to [match/counter] the United States’ and the European Union’s influence,” he said.

Colonial tropes and postcolonial tricks

Kenya’s William Ruto at FOCAC. Leaning West while walking East, saddled with debt and an unfinished standard-gauge railway, the Ruto government is keen to get back into Beijing’s good books. Photo courtesy: State House Kenya.

Although imperial powers finally withdrew most of their flags and armies from the global south in the mid-20th century, economists and historians argue that the underlying patterns of colonial appropriation remain in place and continue to define the global economy. Imperialism, they insist, never ended. It just changed form, draining $152 trillion from the global South since 1960.

Professor Emmanuel Tatah Mentan, a renowned Cameroonian author, academic, and fervent social justice advocate, raises worries that Africa-plus-One summits usually end up in “borrowing arms” to enhance the repressive capability of the African regimes.

“Let us depart from pointing fingers [and] give reasons why industrial policies fail: all countries clamouring for African natural resources are not good Samaritans. All are sharks,” Mentan told African Arguments.

“We have long known that the industrial rise of rich countries during the colonial era depended on extraction from the global South (mostly Asia and Africa), which was used to pay for infrastructure, public buildings, and welfare states in Europe – all the markers of modern development. The costs to the South, meanwhile, were catastrophic: genocide, dispossession, famine and mass impoverishment,” he said.

Mentan loathes the Africa-plus-One summits, stating they incarnate “existing distortions, political capture, and the idea of picking winners” based on some variant of comparative advantage.

“Besides the analytical problem, a common issue is that industrial policies are too easily captured by politically powerful groups who then manipulate it for their own purposes rather than for structural transformation.”

Ondo Ze, Political Science Lecturer and Researcher at the Omar Bongo University in Gabon and a member of the Centre of Studies and Research on Geosciences Politics and Prospective says global powers are using the summit diplomacy to perpetuate a paternalism bequeathed from the imperial era.

“For example, China is investing heavily in African infrastructure, as part of its “string of pearls” strategy,” Ondo Ze tells African Arguments. “Russia favours military and security cooperation, while Turkey and Japan seek to develop their industrial opportunities. India, for its part, aims for energy independence while positioning itself as a credible alternative to China.”

Despite its needs for investment, economic development, security and political stability, Africa, Ondo Ze argues, remains “confined” to the role of supplier of raw materials and geopolitical node and weak actors. As such, Africa-plus-One summits are fuelled by “too much diplomatic naivety” of African chancelleries, the low level of competence of negotiators from some African and the clientelism of African elites.

“All these prevent balanced negotiations and serve the interests of foreign partners rather than those of African people in the face of actors who come not out of friendship or philanthropy but to advance their interests,” Ondo Ze said.

Experts including researcher, Jesper Bjarnesen of the Nordic Africa Institute, agree that a deepening democratic tradition in African states will improve the political leverage of African leaders, and also ensure that the gains of international trade agreements benefit the broad majority rather than simply the political elite.

At the same time, subregional and continental integration, as envisioned by the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement, will strengthen Africa’s global standing in a way similar to that of the EU in the European context.

“A clearer articulation of African visions and interests in the global arena will be important to show that African states are not just passive receivers of assistance from more wealthy global actors (as the dynamic has tended to be historically), but are forward-looking and visionary with regard to the future of their countries and their people,” Bjarnesen said.

“Africa as a continental bloc will become increasingly influential in global politics but in addition to the history of violence and exploitation that has marginalised African voices and interests, African leaders have more often than not tended to their [personal] interests rather than those of their people.”