Iran sent at least nine cargo flights to Sudan between December 2023 and July 2024, coinciding with a rapprochement between the two countries, as Iranian weapons appeared on the battlefield in Sudan for the first time.

This is the conclusion of a new report by the Conflict Observatory, a research consortium funded by the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations.

The report states, “The research team is nearly certain that Iran facilitated weapons to the Sudanese Armed Forces via flights by EP-FAB [a cargo plane belonging to Qeshm Fars Air] to Port Sudan International Airport between December 2023 and July 2024.”

This conclusion was based on the following:

- Identification of nine flights by a cargo plane (EP-FAB) from Tehran to Port Sudan.

- Four of the flights ended their journey at the Iranian Air Force apron of the Mehrabad Airport, Tehran, suggesting potential military cargo.

- Several of the flights turned off their ADS-B transmitters before landing, which the researchers say is “a tactic that suggests deliberate obfuscation and military activity because it is not observed for civilian flights.”

- Iranian weapons appeared on the battlefield in Sudan after these flights began.

- The Iranian cargo plane, EP-FAB, has a previous history of facilitating weapons shipments. It is owned by Qeshm Fars Air, which is sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department for delivering weapons shipments to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (Qods Force) in Syria.

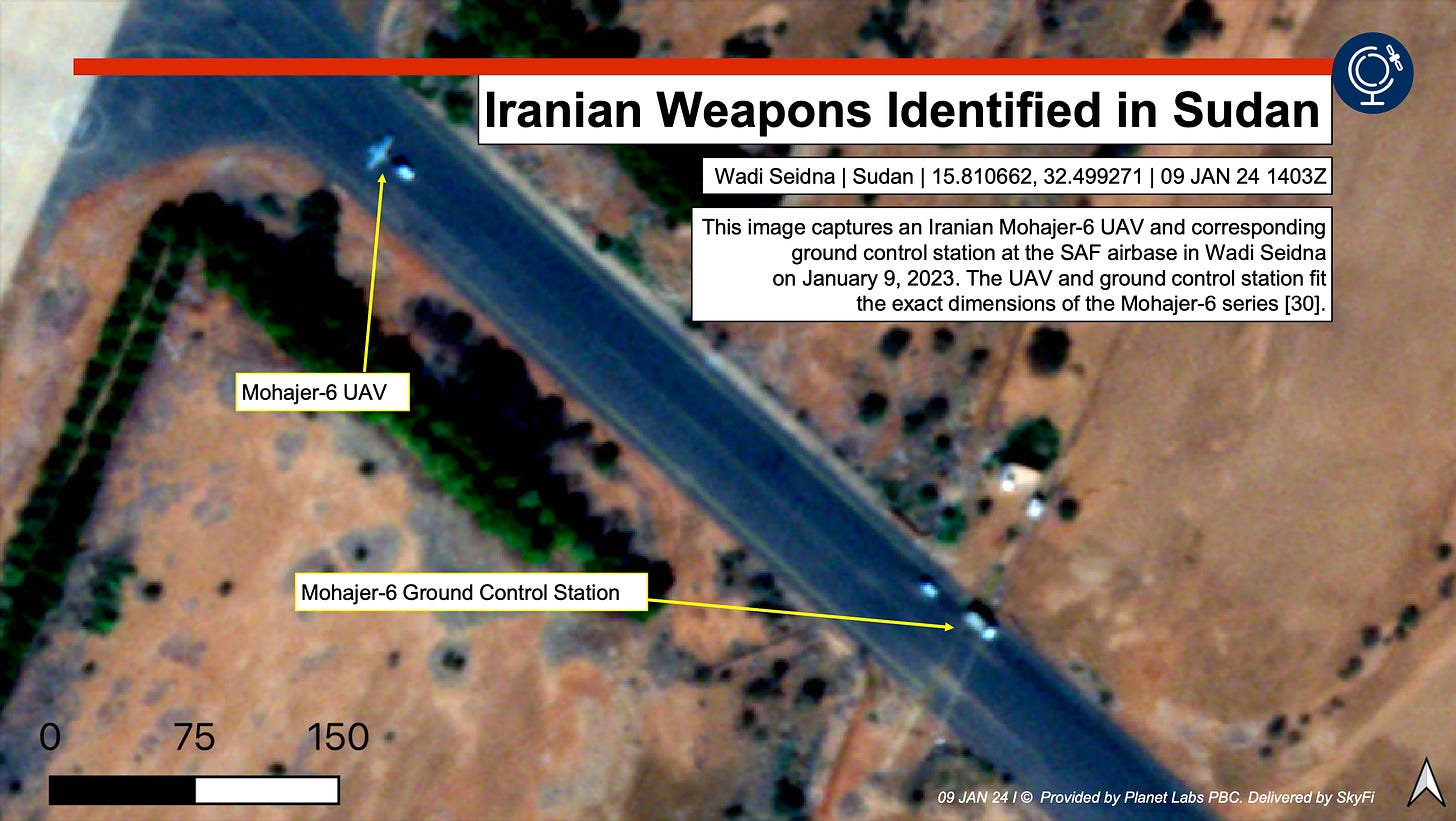

The weapons provided by Iran include Mohajer-6 attack drones and ground control stations, other drone variants, artillery, and possibly other supplies and equipment.

“The beginning of the Iranian flights in December coincided with a Sudanese Armed Forces offensive in January and February, and almost certainly provided weapons to aid that campaign,” said Justin Lynch, the lead author of the report.

A timeline included in the report shows when the confirmed and probable Iranian flights took place, landing in Port Sudan, which is the headquarters of the Sudanese military regime. The research period covered only through July 2024, so subsequent Iranian flights could have taken place since then.

Several of the flights originated in Tehran but stopped first in Bandar Abbas, on Iran’s southern coast, which is a key site for Iranian drone use and naval activity. Then they traveled around the coast of Oman and Yemen to Sudan, avoiding Saudi airspace.

Researchers used high-resolution commercial satellite imagery as well as commercially available flight tracking programs, which use signals from airplanes’ transmitters, as well as radar from ground sources.

Sudan War Monitor previously used publicly available flight data to report on a handful of these Iranian flights, but the new report is much more comprehensive and details additional flights that were not previously reported elsewhere.

The Conflict Observatory also cited open source evidence of Iranian weapons in Sudan. For example, this video shows RSF troops with a drone that they shot down in July in Omdurman. It is a single-payload UAV similar to Iranian variants used in Yemen.

Below are additional images included in the full report, which can be downloaded here.

While Sudan’s military has acquired weapons from many sources in the past, including China and Russia, Iranian weapons shipments are the fruit of fresh political developments in the region, and in Sudan itself.

Prior to normalizing relations with Iran in July, Sudan had frozen its diplomatic ties with Tehran for the past eight years, in solidarity with the government of Saudi Arabia, after attacks on Saudi diplomatic missions in Iran in 2016.

Historically, Sudan and Iran are not closely connected either culturally or politically, but relations between the two countries flourished in the mid to late 1990s, amid tense relations between Sudan and Egypt, and between Sudan and Saudi Arabia. Sudan’s ruling National Islamic Front played host to the Saudi dissident Osama Bin Laden and the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, which attempted to assassinate Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in 1995, with the support of Sudanese intelligence agents.

Sour relations with Arab neighbors forced Sudan’s National Islamic Front to turn farther afield for military and economic assistance in its wars against secular rebel groups operating in southern and western Sudan. Iranian military hardware and training bolstered the Sudanese war effort well into the 2000s. However, after 1999 Sudan worked to repair relations with Arab states and turned increasingly to China for economic and military assistance, reducing the importance of ties with Iran.

These latest developments revive the former Sudanese-Iranian partnership, and signal fresh interest by Iran in the Red Sea region. In addition to its partnership with Sudan’s military, Iran supports the Houthi movement, officially called Ansar Allah, which controls parts of Yemen.